Bob Mackin

Christy Clark was a walking, talking contradiction.

On her 2,345th day as BC Liberal leader — 10 days after becoming the ex-premier — she shocked the province and announced her resignation from politics.

She loved to campaign. But govern? Not so much.

She was a political animal who didn’t want to be in the capital city. She called Victoria a “sick culture” and cancelled the Legislature sitting last fall, to campaign and fundraise instead. She really loved to raise money for the party from corporations because it meant a $50,000-a-year bonus and a sport utility vehicle provided by a donor.

Clark and Coleman, December 2016.

She preached fiscal responsibilty, but scooped millions of dollars out of the public treasury to spend on advertising campaigns and events, like the Times of India Film Awards, which were strategically designed to help the party gain votes at election time.

When the NDP was in power in the 1990s, it was a sin to waste money on such activities. But when she had her hands on the purse, there was no limit.

She sported a pink T-shirt for a photo op to battle bullying in schools on the last Wednesday every February, but did nothing to give B.C.’s downtrodden a voice. She prolonged the tradition of party discipline, which made her the bully in chief.

She came to power promising openness, but ran a government where her staff trained others to not write things down, delete what they did write down and use non-government email and apps to evade freedom of information laws.

She was a career politician who enjoyed an interlude as an open line radio talkshow host. But, as premier, she refused invitations to be a guest on open line radio in the province’s biggest markets.

She pledged to be a leader who wouldn’t run away, but when scandal visited — and it visited often — she made herself scarce for the first 24 to 48 hours, hoping the media and public would move onto something else. Sometimes it worked, sometimes it didn’t.

In the midst of a real estate bubble, driven by massive inflows of Chinese money, and rising homelessness, she left her Mount Pleasant house and moved to a bigger, posher one in Dunbar registered to a party donor connected to one of her biggest supporters.

She represented a riding in Kelowna, but never followed through on a promise to buy a house there. Where did she stay on those rare occasions when she visited Kelowna? She spent on Galiano Island vacation property instead.

She was fond of repeating the jobs and families mantra. She gave many government jobs and contracts to friends of the party. Her ex-husband Mark Marissen and one of her brothers, Bruce Clark, were not only her inner circle, but powerful influences in the party.

After the election, she pretended to be humble and threw a hail mary with that embarrassing “clone speech” that adopted the heart of the NDP and Green platforms. Instead of driving a wedge into the alliance, it ignited an identity crisis in the Liberal camp; her party’s conservative wing felt betrayed. She claimed she listened to B.C.’s divided populace, which wanted politics done differently. But that was all talk. She only wanted another election and the Lieutenant Governor, a Liberal rancher, wouldn’t put up with her nonsense.

Clark liked to lecture her NDP opponents on the qualities of a true leader, which include not hiding or running away. Unlike Bill Vander Zalm, Mike Harcourt, Glen Clark and Gordon Campbell, Clark’s resignation was a two-step process with the second part delivered by news  release.

release.

Career politician Rich Coleman became the interim leader in the most awkward fashion. At a news conference with caucus standing behind him in Penticton, he was on the verge of tears and stumbled over his words. “What she’s given this province should never be forgiven… forgotten.”

Coleman as interim leader could be a tantalizing prospect if Horgan wanted to call a snap election and convert his minority government into a majority. The Langley bloviator is tied inextricably to the ultimate Liberal power broker, Patrick Kinsella, and has extensive political baggage. Many believed Coleman to have been the real premier since 2011, much like Dick Cheney was to the George W. Bush White House. Coleman would be such a convenient target, that the biggest challenge for a quickie NDP campaign would be limiting the number of attack ads.

Look for ex-Finance Minister Kevin Falcon to attempt a comeback in a leadership race. Former Advanced Education Minister and Attorney General Andrew Wilkinson has acted like a leader for months and is exploring a run. Could a reform-minded outsider emerge? Or could the post-election in-fighting lead to a split in the free enterprise coalition and resurgence of the B.C. Conservative Party (which has a convention scheduled for Sept. 30)?

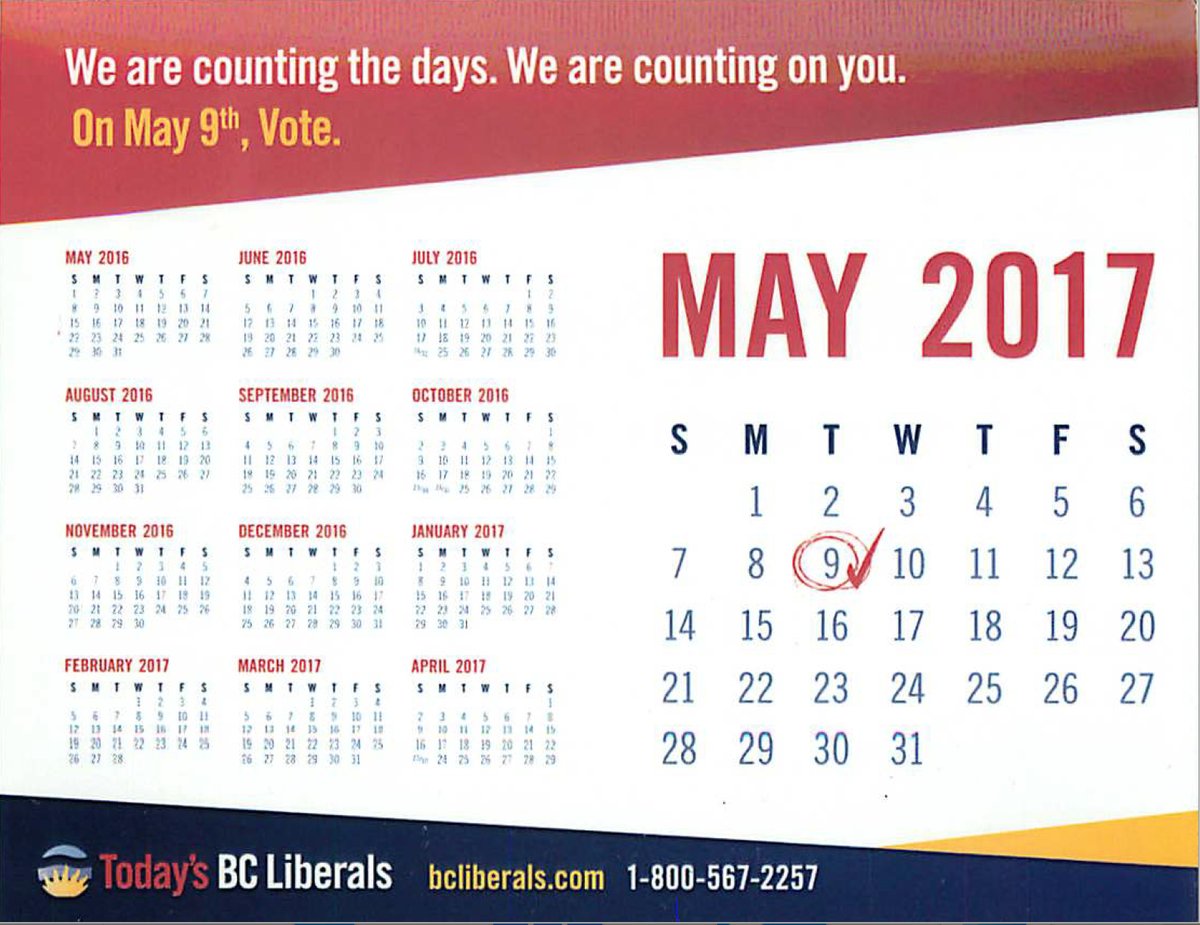

This is not the year that the party had in mind. It lost its majority on May 9. Lost a confidence vote on June 29. Lost power on July 18. It lost its leader on July 28. And the RCMP investigation into illegal donations from lobbyists is ongoing.