Bob Mackin

Aug. 15 was the latest milestone in Vancouver’s bid for the 2030 Winter Olympics.

That is when NDP Tourism, Arts, Culture and Sport Minister Melanie Mark received a mini business plan from the Canadian Olympic Committee.

B.C. Sport Minister Melanie Mark (BC Gov)

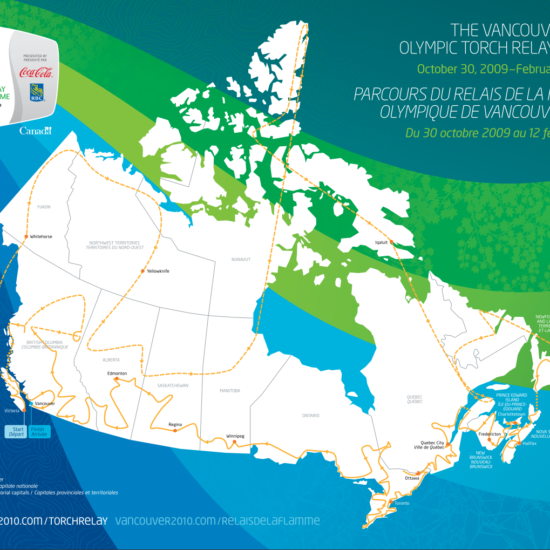

Mark saved the date as the deadline for COC president Tricia Smith to make the case not only for provincial funding, but for the province to assume deficit liability, just like it did for Vancouver 2010. In a June 24 letter, Mark asked Smith, who is collaborating with the Four Host First Nations, to explain whether Vancouver, Whistler and the Musqueam, Squamish, Tsleil-waututh and Lil’wat would share costs and risks. The COC had already been planning to make formal proposals to B.C. and federal treasury boards in October.

“Consideration of hosting major international sporting events requires significant time and resources by all parties,” said Mark’s letter. “The experience in preparing for the 2010 Games, the magnitude of an Olympic and Paralympic Games is very large and complex, and requires careful consideration by all levels of government and host First Nations. As you will appreciate, our environment has changed since 2010, particularly in relation to the risks and challenges created by pandemics, evolving domestic and international security threats, and the effect of global climate change.”

The COC’s July 8-published financial estimates suggest the 2030 Winter Games would need more than $1 billion from taxpayers, including $299 million to $375 million to renovate or retrofit venues, $165 million to $267 million for Olympic villages, and $560 million to $583 million for security. The great unknown is essential services, such as waste collection, ambulances and paramedics, emergency planning, airports and border control.

COC hired construction consultant BTY Group to estimate the venues and villages costs. Michael Gabert, BTY’s director of cost management services, said the company responded to the COC’s call for qualifications in March and produced an initial report in April.

Estimates were based on interviews with venue operators, but not site visits.

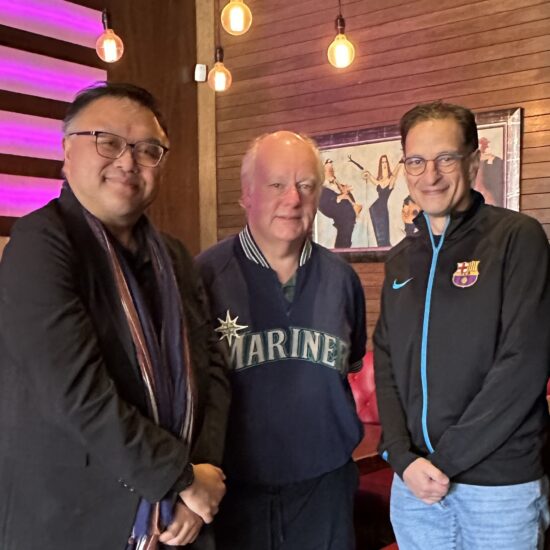

Michael Gabert (left) and Rob Wilson of BTY Group (BTY)

“We were provided with budgets and scope from the venue operators and owners, and we went through a series of meetings with them to review the information that they had available to look at the scope, look how they develop their costing,” Gabert said in an interview. “And then we provided our own opinion on the capital costing for it.”

Gabert said each venue operator provided a breakdown for maintenance, renewal and potential upgrades, such as a new HVAC system, structural upgrades or major modifications. Some venue operators had more detail than others. BTY also advised on allowances for soft costs, project management for design and engineering and contingencies.

“We haven’t gone into kind of any specific detail about what specific design or what specific structural items we would need to be considered,” added Rob Wilson, BTY’s director of project monitoring and lender services. “From a conceptual and a high level that will evolve, as quantity surveying always does, when more details are received.”

The COC-released report said the venue estimates include up to 45% built-in for design, construction and other contingencies and inflation. The estimates for athletes’ villages in Whistler, Sun Peaks and Vancouver are proposed lump sum payments to developers for Games-time use. The Vancouver Olympic Village is proposed for the Jericho Lands, part-owned by the MST Development partnership of the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-waututh.

Gabert declined to comment on individual venue estimates, but agreed there would be more work needed to bring an older building to code and readiness for 2030. The 1963-opened Agrodome and 1968-opened Coliseum are the oldest indoor venues proposed for 2030, while the 2008-opened Richmond Olympic Oval would require retrofitting to accept a long-track speedskating oval again. Neither Vancouver nor Richmond have published cost estimates.

What next?

If the B.C. and federal governments approve financial support and the COC proceeds to making a formal bid book for the IOC by year-end, then Gabert said detailed engineering studies would be required for each venue to develop more-accurate pricing.

PNE Agrodome (Mackin)

“You can start to quantify in a more detailed basis, the amount of work that’s required, you can drill down further into what specific materials or equipment are required and start sourcing pricing directly for those items that you know are going to be needed,” he said.

On July 20, Vancouver city council rejected holding a bid plebiscite during the Oct. 15 civic election, but opted to carry on exploring a bid against 2002 host Salt Lake City and 1972 host Sapporo, Japan. The International Olympic Committee wants to decide by the end of May 2023 at its annual meeting in Mumbai.

On Aug. 9, Mayor Kennedy Stewart wrote to Mark and Federal Sport Minister Pascal St-Onge to ask whether the senior governments would fund a 2030 bid.

Council directed staff on July 20 to move forward in negotiating multiparty agreements, after Deputy City Manager Karen Levitt had warned there was not enough time and too many questions about costs and risks for an already burdened bureaucracy at 12th and Cambie.

The 2010 Games are believed to have cost $8 billion, all-in. The true costs are unknown, because the Auditor General never did a post-Games study, the organizing committee was not subject to the freedom of information law and its board minutes and financial files won’t be open to the public at the City Archives until fall 2025.

Support theBreaker.news for as low as $2 a month on Patreon. Find out how. Click here.