Bob Mackin

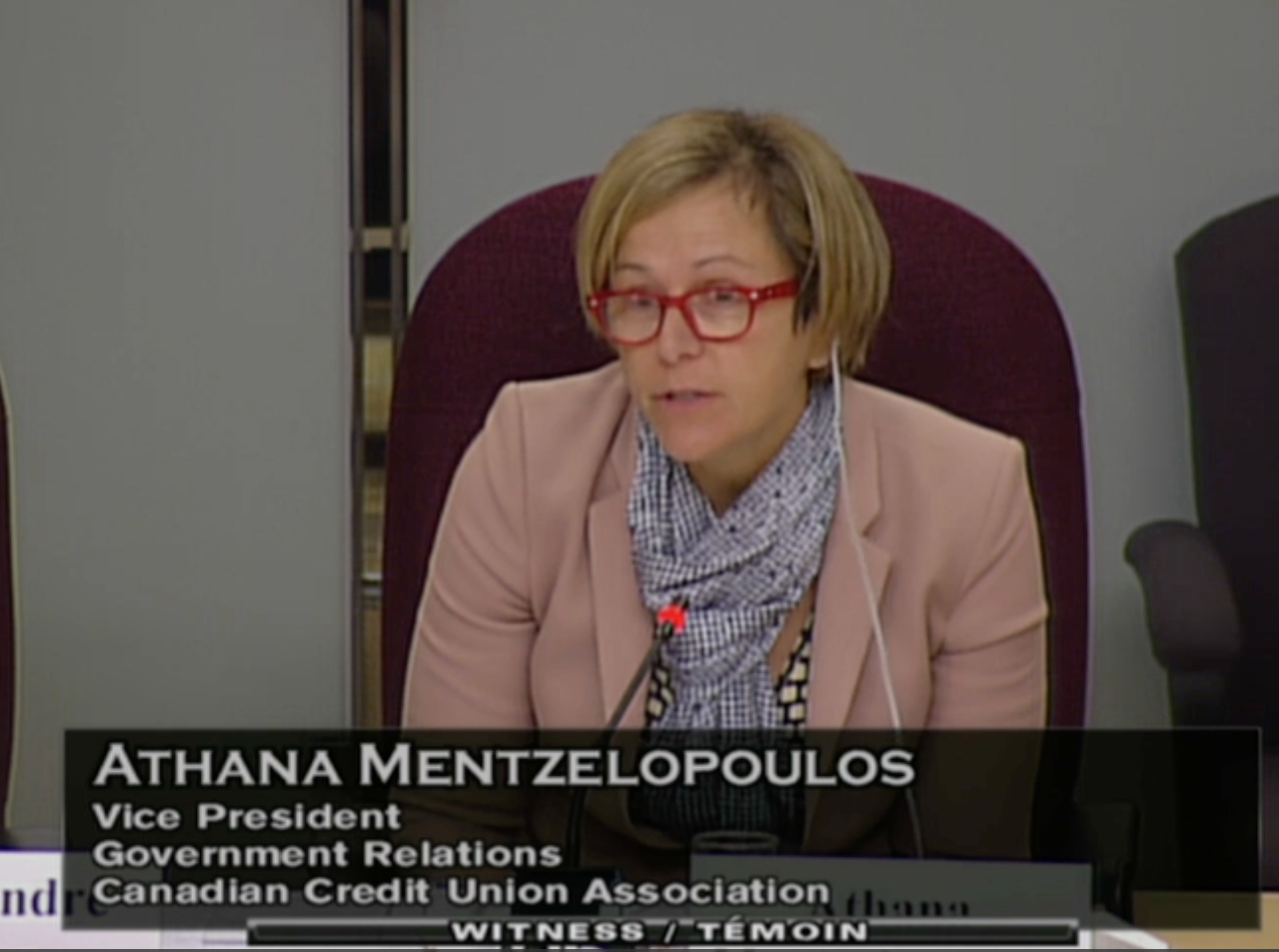

A controversial figure from ex-B.C. Premier Christy Clark’s inner circle has become the top lobbyist for Canada’s credit unions.

Athana Mentzelopoulos was fired as the $284,052-a-year deputy finance minister and took a $474,552.51 golden parachute when the BC Liberal dynasty ended in mid-July. On Sept. 1, the Canadian Credit Union Association named Mentzelopoulos the vice-president of government relations. Her first major project is the association’s Oct. 16-17 Government Relations Forum and Hike the Hill, for credit union leaders and directors to meet members of parliament to discuss credit union concerns.

Mentzelopoulos was one of the most powerful deputy ministers in the Clark administration and was granted the severance package when Clark signed orders-in-council on July 17 to revoke Liberal cabinet appointments the day before the NDP’s John Horgan was sworn-in as premier.

The CCUA news release emphasized Mentzelopoulos’s prior post, in which she was the top bureaucrat responsible for the B.C. Securities Commission and credit union regulator Financial Institutions Commission.

“Given Athana’s responsibility for both CCUA’s provincial and federal government relations, she will be based in Toronto, travelling often to Ottawa and other provincial capitals,” said the news release from the national trade group for member-owned financial institutions.

While Mentzelopoulos has registered to be a federal lobbyist, post-employment restrictions for senior management in B.C’s public service include a one-year ban on lobbying of otherwise making representations “for any outside entity to any ministry or organization of the government in which you were employed at any time during the year immediately preceding the termination of your employment.”

NDP government-tabled amendments to B.C.’s lobbying law include a ban on lobbying “in relation to any matter” by an ex-public office holder for two years after leaving government.

“Ms. Mentzelopoulos is and will be in compliance with all requirements as she works with credit union government relations representatives across Canada,” CCUA spokeswoman Janet Gibson-Eichner said by email.

Bridesmaid’s baggage

Dermod Travis of anti-corruption watchdog IntegrityBC said Mentzelopoulos is cashing-in by leveraging her government-cultivated relationships and insider knowledge. Her new job, he said, raises questions about regulatory capture.

“Even if she had to wait a year before lobbying, all she has to do is walk down and to talk to whoever is in the next office, whoever is handling the lobbying in that 12-month period, and sharing all of her knowledge,” Travis said. “The revolving door swings too fast between senior posts in the public sector and government relations posts in the private sector.”

Late Roderick MacIsaac, one of the health researchers wrongly fired.

Mentzelopoulos was nicknamed “the bridesmaid” for performing that role when Clark wed fellow Liberal strategist Mark Marissen in 1996. Mentzelopoulos and Clark were both political appointees in Liberal Prime Minister Jean Chretien’s administration in 1993. Mentzelopoulos served in various capacities in ministerial offices in Ottawa before moving to Victoria in 2004 as deputy minister of intergovernmental relations and later government communications, under Premier Gordon Campbell. She returned to Ottawa for a two-year stint with Health Canada in 2009 before Clark took power in 2011 and named her to head B.C. government communications.

Perhaps her defining moment in B.C. was approving a 2012 press release that falsely claimed the RCMP was investigating a data breach in the Ministry of Health.

Eight researchers were wrongly fired. One of them, Roderick MacIsaac, died by suicide in late 2012.

In a damning April 2017 report on the scandal, Ombudsperson Jay Chalke wrote: “Ms. Mentzelopoulos conceded that she thought that it was important to have the RCMP in the press release, ‘because I assumed that it was true’.”

In March 2016, Clark shuffled Mentzelopoulos out of the tourism and labour portfolio and into finance, under minister Mike de Jong. During de Jong and Mentzelopoulos’s management of the finance ministry, real estate corruption and money-laundering at casinos flourished in B.C.