Bob Mackin

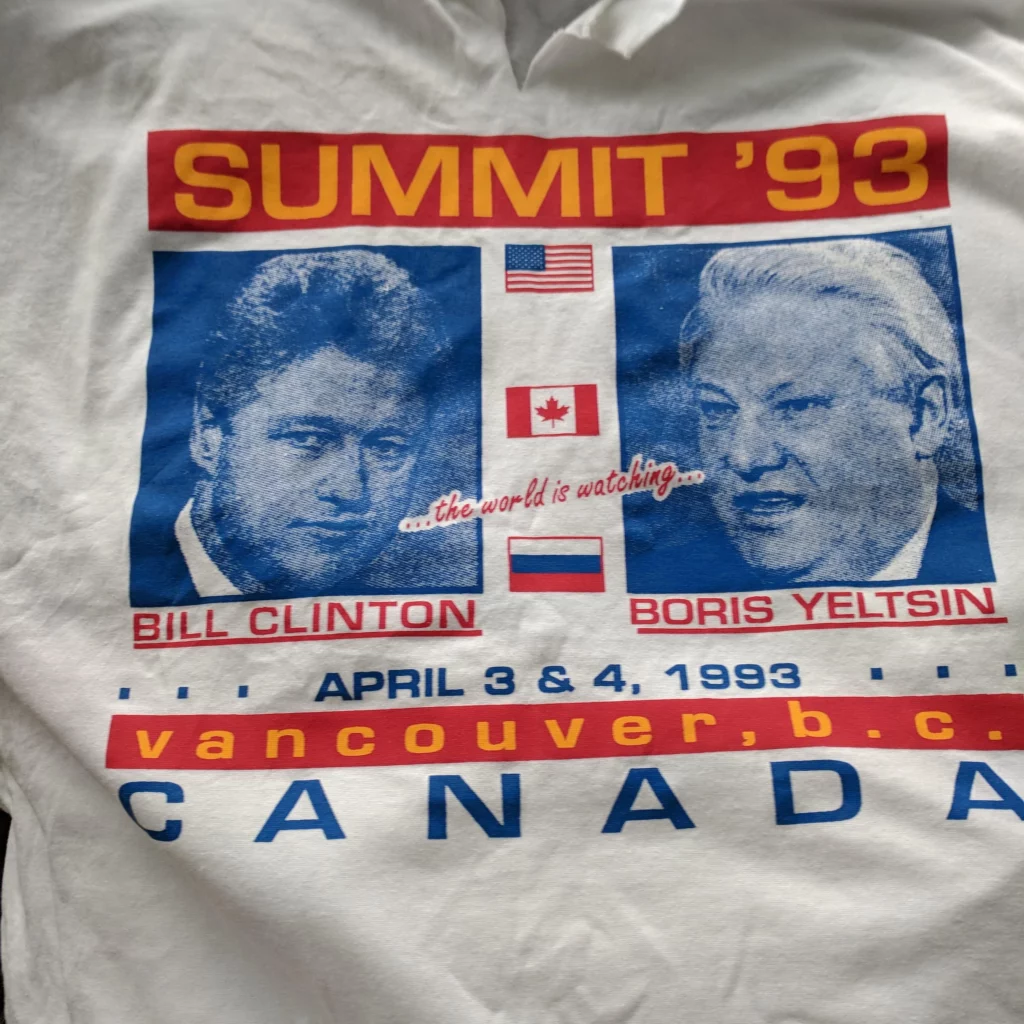

Bill Clinton and Boris Yeltsin had a lot to talk about in their first summit meeting, 30 years ago in Vancouver on April 3-4, 1993.

Vancouver Summit T-shirt (Reddit)

But the new U.S. President saved some quality time for the host, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, to discuss contentious trade, resources and environmental issues.

Mulroney had announced more than a month earlier that he would resign after eight years in office, pending the Progressive Conservative Party’s choice of a successor. He met with Clinton and Russia’s Yeltsin and a small group of aides for lunch and then held a one-on-one meeting with Clinton at Norman MacKenzie House, the University of B.C. president’s mansion, on April 3, 1993.

“Tell Mulroney that U.S. law provides little discretion on the softwood lumber countervailing duty case,” said Clinton’s declassified White House briefing notes. “Deflect Mulroney’s request for a farewell White House meeting in May. Reiterate your concern about the Windy Craggy Copper Mine project and the need to resolve the Victoria municipal sewage issue.”

White House aides told Clinton that the summit allowed Mulroney to project himself as an “elder statesman” and hosting such an event “resonates well with a Canadian public which has long memories.” It cited Canada’s hosting of historic meetings between President Franklin Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill during World War II.

“Next to the summit, you will find Canadians seized by electoral politics. With a new Prime Minister set to take office in June, and federal elections which must be held no later than December 12, the country has turned its attention away from its ever-present and increasingly insoluble unity question. Even the economy has receded as an issue, due to the arrival of the long awaited recovery.”

That new Prime Minister, Clinton’s aides correctly predicted, would be the 48-year-old Minister of Defence and Vancouver Centre MP named Kim Campbell.

“You can fully expect that within two months, you will be dealing with Canada’s first female Prime Minister.”

Clinton’s aides anticipated Mulroney would ask about progress on passing the new trade deal and told him to say that he is “fully engaged in pressing for North American Free Trade Agreement ratification when the package is complete and submitted to congress.”

Mulroney was expected to highlight B.C. issues, not only softwood lumber, but two environmental controversies.

Site of the 1993 Vancouver Summit, Norman MacKenzie House (UBC Communications/Flickr)

“You may want to tell Mulroney that the U.S. will continue to make the case against the [Windy Craggy] project, and may take it to the International Joint Commission (a bi-national, semi-autonomous body established by the U.S.-Canada Boundary Waters Treaty of 1909),” it said.

“We recommend you tell Mulroney that [Victoria’s untreated sewage] is a big issue in the northwest, particularly given the burden on local American taxpayers who are doing their fair share to keep [Puget] Sound clean.”

The briefing notes mentioned that Mulroney’s staff wanted to visit Clinton at the White House on May 23 or 24, as part of Mulroney’s farewell tour to Western capital cities.

“Canadian preference is for a small, personal lunch and a tour d’horizon. Given the fact that you will have met twice with Mulroney in three months, we recommend that you give Mulroney a non-committal answer for the present.”

In his script of prepared answers, Clinton’s aides suggested he tell Mulroney: “It may be difficult with my schedule prior to the G-7 summit in July but I will get back to you.”

Mulroney eventually made the trip June 1-2.

In his files about the Yeltsin meetings in Vancouver, Clinton was reminded he would be the first Democrat President to meet a Russian counterpart since Jimmy Carter and Leonid Brezhnev in 1979 at Vienna. The Vancouver Summit would be “unique,” because the Cold War was over and it was programmed to focus on economic issues.

“No longer adversaries, we now find ourselves as one of the strongest supporters of Russian reforms.”

Though Yeltsin would receive a US$1.6 billion aid package in Vancouver, he also had a great deal to lose at home. A Russian constitutional referendum loomed three weeks later.

Canada’s first female Prime Minister, Kim Campbell (Government of Canada)

“The Vancouver summit helps Yeltsin in many ways,” said the briefing notes. “A trip abroad at this time shows his people and the world that things have settled down at home and he has weathered the crisis. He gains in stature from being treated as an equal by the American President — a perception underscored by the fact that your first meeting abroad with a foreign leader is with the leader of Russia.”

It said Yeltsin could quell his Russian critics who called him too pro-Western, if he could bring home “tangible assistance under the mantle of mutual advantage and partnership.”

Clinton and Yeltsin met again in July 1993 at the G-7 summit in Tokyo, then 16 more times through the years. Four meetings were in Moscow and one in Washington, D.C.

In 2000, Clinton traveled to the Kremlin to meet Yeltsin’s handpicked successor, Vladimir Putin.

Over the next two decades, the former KGB intelligence officer took Russia back to an autocratic state and started wars with Georgia and Ukraine, undoing all the work that began in Vancouver on the first weekend of April in 1993.

Support theBreaker.news for as low as $2 a month on Patreon. Find out how. Click here.