Bob Mackin

The Winter Olympics aren’t returning to British Columbia in 2030, after the NDP government announced Oct. 27 it would not back another multibillion-dollar mega-event, even with many venues left over from Vancouver 2010.

The International Olympic Committee will choose between 2002 host Salt Lake City and 1972 host Sapporo, Japan next fall, assuming one doesn’t drop out sooner.

B.C. Sport Minister Melanie Mark (BC Gov)

In late June, then-NDP tourism and sport minister Melanie Mark demanded the Canadian Olympic Committee and its First Nations partners provide a mini business case by mid-August for consideration by cabinet.

Mark warned them not to assume taxpayer support and she indicated there was already a daunting list of socio-economic, geopolitical and environmental challenges facing B.C. She handed the portfolio to predecessor Lisa Beare in September and it was Beare’s job to be the bearer of bad news to the bid team earlier this week.

When the plan was submitted, according to one source, there were still many holes that could not be quickly filled in time to satisfy the bidders’ late November deadline to firm-up government support to be ready for “targeted dialogue” negotiations with the IOC beginning in December.

What went wrong?

Timing

It was simply a bad time for a Games bid, with an ongoing pandemic and shortage of doctors and nurses in a year marked by rising interest rates and inflation. Not to mention the fear of a recession in the new year.

A public backlash forced Premier John Horgan to scrap his plan to spend nearly $800 million on replacing the aging Royal B.C. Museum with a new Indigenous-themed institution. Horgan is handing the reins to David Eby on Nov. 18, just over a month after angry municipal voters dumped incumbent mayors, including 2030 bid booster Kennedy Stewart in Vancouver.

Olympic Village site uncertainty

The bid proposal revealed in June said that First Nations-owned MST Development’s Jericho Lands and the Heather Lands were candidates for athlete accommodation in Vancouver.

Instead of choosing one or the other, the latest version added the former Liquor Distribution Branch warehouse site in East Vancouver, but suggested an unspecified other site could also fit the bill for an estimated 410 non-market units of varying sizes.

The proposal suggested the Whistler Golf Club’s driving range and/or Cheakamus Crossing, the site of the 2010 Whistler athletes’ village, for 579 units.

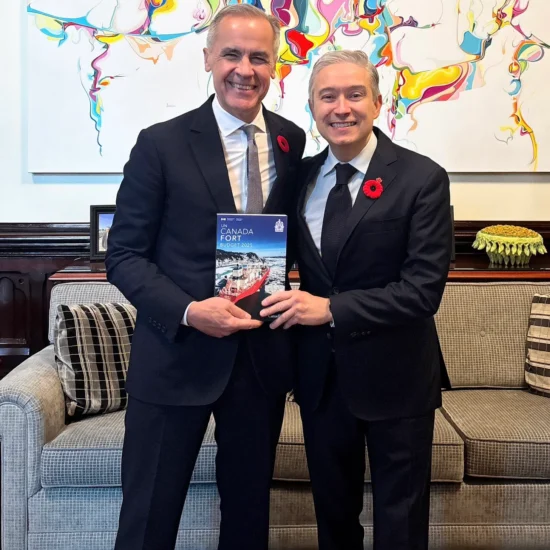

David Eby and John Horgan (BC Gov/Flickr)

Costs

The bid sought $2.12 billion from governments in cash and in-kind funding in 2022 dollars, estimated to be worth $2.715 billion by 2030. Half of that from Ottawa and 35% from B.C., which would have doubled as the deficit underwriter — a role that the NDP ultimately rejected.

It also contemplated $1.6 billion in allowances for contingencies and cost escalation.

“The proposal looks to the municipalities and [First] Nations to contribute land for the villages and in-kind essential municipal services,” said the latest version of the document.

The budget bundled security with essential services totalling $756 million ($958 million in 2030), with the same low-ball estimates for public funding of venues ($286 million) and villages ($267 million).

The proposal did not offer a site-by-site cost breakdown, though there is a laundry list of required upgrades attached.

Governance

The NDP’s checklist called for explanation of governance for an “Indigenous-led” Olympics.

Just like 2010, the organizing committee would be not-for-profit. This time a 25-member board of directors would include two members from each of the Four Host First Nations — in 2010, there was only one representing all four. Secwepemc, on whose territory Sun Peaks sits, would also get a seat. The federal, B.C., Vancouver and Whistler governments and COC and Canadian Paralympic Committee would get two each, plus a seat reserved for a recent Olympian and a recent Paralympian.

Whither Richmond?

The showcase urban venue for the 2010 Winter Olympics was the Richmond Olympic Oval. When Burnaby balked at rising costs, Richmond enthusiastically jumped in and also found a way to pay its share by selling neighbouring land condo towers. The Oval is now a multisport community centre with an interactive Olympic museum, often criticized for its reliance on operating subsidies.

Richmond Olympic Oval hosted a temporary anti-doping lab in 2010 (Richmond)

Richmond was not a partner with Vancouver and Whistler in the 2030 bid exploration with the Four Host First Nations. Chief administrative officer Serena Lusk’s letter was included in a package of 100 endorsement letters, but it stands out from others.

“However, while supportive of the bid effort, Richmond is not considered a partner city,” Lusk wrote. “As a result, our support for the use of the Richmond Olympic Oval is provided within the context that acceptable terms are negotiated and that the City of Richmond will not assume any share of the financial costs, risks or liability that the organizers will incur.”

The proposal did not indicate how much it would cost to retrofit the Oval to bring back long-track speed skating in 2030. The list of upgrades, however, is long.

Required: Removal and replacement of all hard court and plastic flooring, batting cage, divider curtains, dasher boards and glass; Removal and reinstallation of elevator; Upgrade and replacement of ice plant and HVAC; Replacement of ice resurfacing machines.

Legacy upgrades: Contribution to the creation of additional meeting space and contribution to the roof replacement capital fund.

Public attitude

Bid team leaders must’ve known they were skiing uphill.

Their proposal includes an appendix with rosy economic forecasts by PwC, the same firm hired to help sell the 2010 Games.

While PwC’s $5 billion estimate of economic activity before and during 2030 looks nice on paper, how well would it stand up in reality? B.C.’s Auditor General never did an audit of the post-recession 2010 Games, the organizing committee minutes and financial records are hidden until 2025 at the Vancouver Archives and the organizing committee was deliberately incorporated beyond the reach of B.C.’s freedom of information law.

Vancouver Mayor Kennedy Stewart on Dec. 10 (City of Vancouver)

There was a successful plebiscite in 2003 that played a role in the IOC choosing Vancouver for 2010. But, in 2022, no similar appetite for democracy, owing to the IOC and COC fearing a repeat of 2018, when Calgarians narrowly rejected a 2026 bid.

Third-place Vancouver mayoral candidate Colleen Hardwick included a bid plebiscite in her campaign platform after unsuccessfully asking her city council colleagues to put the question on the Oct. 15 ballot.

COC hired Delaney and Associates to gauge feedback from more than 4,500 people who participated in community events, focus groups and an online survey over the summer. Many comments were unflattering.

For instance, there was a sense of “general skepticism.” Workshop participants felt the draft concept statement for the bid was political and abstract. It was also described as “greenwashing.”

Another heading read “clarity required” about the meaning of Indigenous-led, including whether First Nations would help finance the event.

Others were concerned about negative economic impact and misplaced spending priorities. Shouldn’t healthcare, addressing the cost of living and supporting Indigenous communities be at the top of the list?

Some brought up the “corruption and diminished reputation” of the IOC and feared a repeat of the displacement of people and disruption to daily lives that occurred due to the 2010 Games.

Support theBreaker.news for as low as $2 a month on Patreon. Find out how. Click here.