Bob Mackin

Part of the BC Liberal campaign rhetoric is the suite of positive opinions from the world’s major credit ratings agencies.

They are paid handsomely to evaluate a borrower’s ability to pay interest and repay principal.

The ratings agencies are a necessary evil. Not necessarily evil. But they are far from infallible.

B.C.’s total debt, in the February budget (tabled but not passed before the election), is estimated to hit almost $70 billion by the end of next March. The debt was $45.2 billion when Christy Clark took over the premiership from Gordon Campbell in March 2011.

Finance Minister Mike de Jong likes to trumpet the high marks given by credit ratings agencies, but he is keeping a secret.

Career politician de Jong

For three years, between 2012-2013 and 2014-2015, the government paid nearly $1.2 million in fees to three of the ratings houses: Standard and Poor’s, Moody’s and DBRS. Fitch is the only ratings agency that is not paid.

The government signed sole-source contracts to pay fees through March 31, 2017 with S&P ($210,000) and Moody’s ($242,900). The justification form said S&P was “the only credit agency to offer Standard & Poor’s credit rating.” Likewise for Moody’s.

S&P was also paid $207,112,50 for the previous fiscal year. In its contract, the small print reminded the B.C. government that credit ratings are “statements of opinion and not statements of fact.”

The reliability of opinions from credit ratings agencies has come under world media scrutiny since the 2008 Great Recession.

In a 2012 story by the Guardian, headlined “How credit ratings agencies rule the world,” Patrick Kingsley wrote:

Part of the problem is that ratings agencies are funded by the very companies they rate. If you want to be rated, you must pay an agency between $1,500 and $2,500,000 for the privilege, depending on the size of your company. In theory, this creates a conflict of interest, because it gives the agency an incentive to give the companies the rating they want. It could explain why, for much of the past decade, agencies seemed happy not to question either the risks banks were taking, or the accuracy of their accounts.

In 2014, under the headline “Big three credit rating agencies under fire,” the Financial Times reported:

The three main rating agencies, Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s and Fitch, have been seen as at least partially culpable for elements of the financial crisis, from the fiasco of subprime mortgage securitization to tipping Greece into disaster when its sovereign credit rating was downgraded.

Their actual ratings have also come under attack, with academic papers and bank economists analyzing them to find evidence of home bias, subjective error and over-lenient analysis.

One prominent example of a rating gone wrong? In 2009, Moody’s famously reported that investor fears over Greece’s liquidity were “misplaced.”

The European Union stepped in and gave the Greeks tens of billions of dollars in bailouts, to keep the birthplace of the Olympics from collapsing.

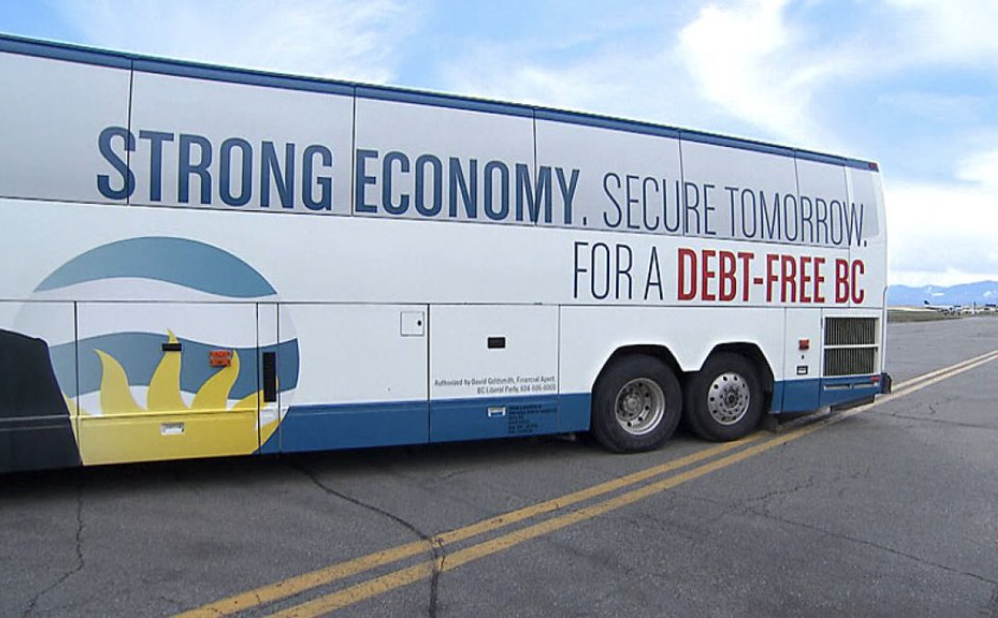

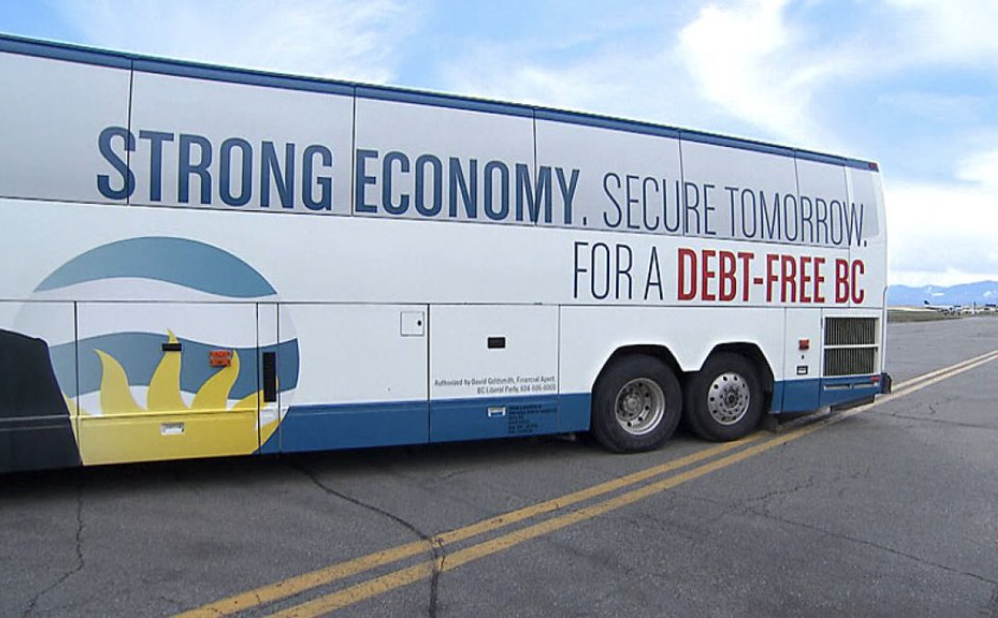

Clark’s misleading 2013 “Debt-Free B.C.” campaign bus.

In January, Moody’s raised a red flag about BC Hydro, which had

an $8.1 billion debt in 2008 that has ballooned to $18.1 billion. The Crown corporation building the controversial Site C dam’s finances are “among the weakest of Canadian provincial utilities.”

“The anticipated increase in debt continues to pressure the province’s rating since it raises the contingent liability of British Columbia,” Moody’s reported.

In a 2011 report about BC Hydro, then-auditor general John Doyle accused the biggest Crown corporation of creative accounting. He famously wrote:

“Expenses that would ordinarily be counted in calculating net income have been deferred to future years (allowed under rate-regulated accounting). While this practice is currently acceptable under Canadian generally accepted accounting standards (GAAP), it creates the appearance of profitability where none actually exists.”

Brad Bennett, the Liberal back roomer that Clark-appointed chair of BC Hydro, is part of the premier’s traveling campaign entourage.

Just like he was in 2013, when Clark’s bus included the ironic slogan “Debt-Free B.C.”

Response Package FIN 2016 63633 by BobMackin on Scribd