Bob Mackin

British Columbia’s 150th anniversary came and went without fanfare. The same can’t be said for the extreme weather systems that gained global attention. Record heat and cold, six months apart. Record winds, rains and floods throughout the fall. Even a tornado.

The weather was the province’s newsmaker of 2021.

The Heat Dome

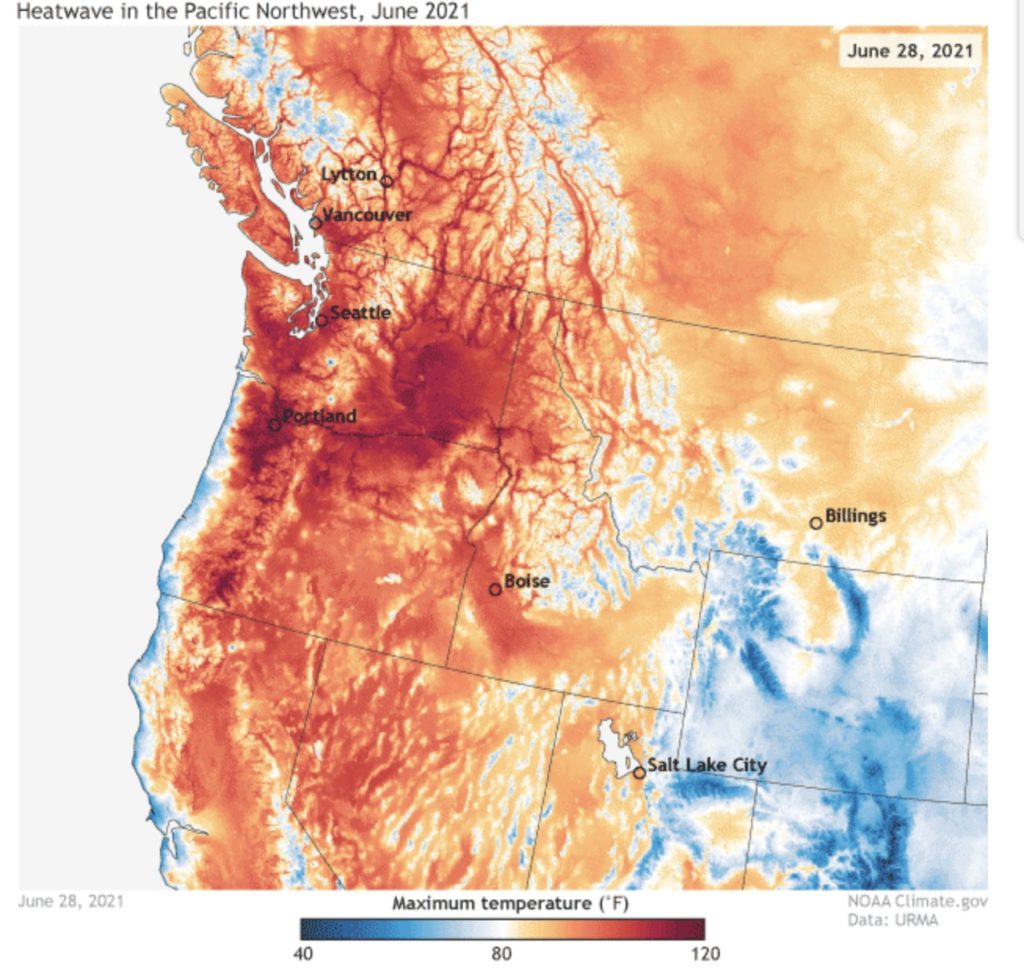

An ominous warning from Environment Canada on June 23.

“A dangerous long duration heat wave will affect B.C. beginning on [June 25] and lasting until [June 29]. The duration of this heat wave is concerning as there is little relief at night with elevated overnight temperatures. This record-breaking heat event will increase the potential for heat-related illnesses.”

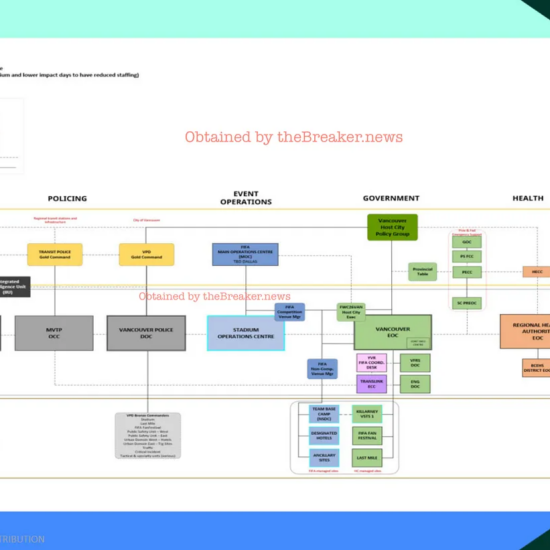

June 28, 2021 (NOAA)

The meteorologists did their job. The politicians? Not so much. The NDP government did not warn the public in a province where air conditioned homes are the exception, not the rule.

On June 29, as the death toll mounted, Premier John Horgan admitted his government was focused on the July 1 lifting of pandemic restrictions.

“Fatalities are a part of life,” he shrugged.

The Coroner estimated 526 heat-related deaths — the deadliest natural disaster in Canadian history.

More than 640,000 chickens and turkeys died in the Fraser Valley. Air conditioning failures forced closures at several COVID-19 testing and vaccination clinics.

As the mercury shot up, records fell. Lytton set a new Canadian record of 45 Celsius on June 27. Two days later, it hit 49.6C. The next day, a wildfire decimated the town of 1,200.

From July 21 to Sept. 14, B.C. was under a wildfire state of emergency. More than 1,600 wildfires burned almost 870,000 hectares around the province.

Drought diary

First the wings, then the fangs.

The third year of looper moth infestations turned evergreens on the North Shore mountains a shade of orange. Earlier than the previous two years, because of the drought.

Another Asian murder hornet was found in the Fraser Valley, but farmers breathed a sigh of relief when entomologists found and destroyed four nests just across the line in Whatcom County.

Meanwhile, coyotes on the prowl in Stanley Park led to dusk-to-dawn closures beginning July 30. There had been 41 reports of coyotes chasing or nipping park visitors, including children. There were also adults who flouted the law and used food to create Instagram moments.

A month later, just in time for a series of Malkin Bowl concerts, further park closures. The Conservation Officer Service sent hunters and trappers in with a goal of culling 35. They killed four by the end of September when the closure was lifted. The headliner of real estate tycoon Ryan Beedie’s invite-only festival? The Killers, of course.

Da bomb cyclone

The remnants of Typhoon Nametheun made their way across the Pacific and brought wind warnings to coastal B.C. on Oct. 20.

A record low pressure reading of 942.5 mb was detected from an offshore buoy Oct. 24. Heavy winds and rain pelted the coast, leading to power outages. It was surfers’ delight in Tofino and other beaches.

Meanwhile, the Canadian Coast Guard’s hands were full with the Vancouver-bound container ship ZIM Kingston, which lost 100 of the “cans” in rough seas off Vancouver Island. Very Vancouver cargo washed ashore, including yoga mats and poker tables. Meanwhile, the crew was evacuated when a fire broke out aboard the vessel off Victoria.

Tornado topples tees and trees

Late afternoon on the first Sunday of November, a waterspout off Vancouver International Airport and a brief tornado warning from Environment Canada.

The waterspout traveled towards Howe Sound and the North Shore, but not before touching down as a tornado at the University of British Columbia golf club. The twister uprooted trees, leaving parts of Point Grey without electricity and bus service. Environment Canada estimated winds from the brief twister at 90 km-h to 110 km-h.

Mid-November monsoons

The heat dome in late June was the deadliest natural disaster in Canadian history. The rains and floods in mid-November? The most-expensive natural disaster in Canadian history.

(City of Abbotsford)

Another atmospheric river spoiled an early season snowpack on Southwestern B.C. peaks and drenched the region from Nov. 13-15 with B.C.’s biggest November super-soaker since 1955. Merritt, Princeton and Abbotsford were hardest hit. A quarter of the Coquihalla Highway destroyed by landslides and bridge collapses.

All road and rail links between the Lower Mainland and B.C. Interior were closed; the Port of Vancouver was effectively cut-off from the rest of Canada during the global supply chain crunch.

As the rains subsided, the winds picked up, keeping the Canadian Coast Guard busy Nov. 15 between the mainland and Vancouver Island. An empty barge in English Bay went adrift and ran aground at Sunset Beach, becoming a pop culture icon.

Just like the heat dome, the NDP government did not warn the public. It eventually declared a state of emergency on Nov. 17 and set about rebuilding the Coquihalla. There was even temporary fuel rationing. The federal government sent soldiers and equipment from Alberta as the Sumas Prairie saw the worst flooding since 1948.

Out of this world

The “intermissions” delivered awesome sights. The clouds parted for heavenly sights twice. Late Oct. 11 and early Oct. 12, the Northern Lights danced across B.C. skies. The weather also co-operated during the longest lunar eclipse of the century during the beaver full moon Nov. 18-19.

Hot start to December

The “parade of storms” that began lashing B.C. on Sept. 14 ended with three more late November atmospheric rivers.

Meteorological winter began Dec. 1 with a taste of… summer?!? Penticton recorded 22.5C on Dec. 1, tying the hottest December day in Canada.

But old man winter had more surprises up his sleeve.

White Christmas

A 3.6 magnitude earthquake jolted Vancouver Islanders out of their beds at 4:13 a.m. on Dec. 17. A week later, a dream come true for some. A White Christmas, to be exact.

Only the fourth in Vancouver in the last 25 years, and the first since 2008.

Pond hockey at the Planetarium on Dec. 29 (Mackin)

Late June brought B.C. the heat dome, late December the ice dome. As the flakes piled up, the temperatures went down around B.C. Environment Canada warned of frostbite and hypothermia, with -35C windchills in northern B.C. and -20C in Metro Vancouver.

Much of the province was under extreme cold or Arctic outflow warnings, which led to 42 record cold temperatures on Boxing Day and Dec. 27.

The thermometer in fire-destroyed Lytton plunged to -25C — a swing of 75 degrees in the space of six months. It was too cold for some COVID-19 testing centres and even BC Ferries sailings between Duke Point and Tsawwassen were curtailed.

It was so cold that many in B.C. weren’t aware it was B.C.’s second major Arctic blast of the year — the first was way back in February, around Valentine’s Day.

All signs of a changing climate or a series of climate coincidences? Scientists lean toward the former.

Stay tuned for 2022.

Support theBreaker.news for as low as $2 a month on Patreon. Find out how. Click here.