Bob Mackin

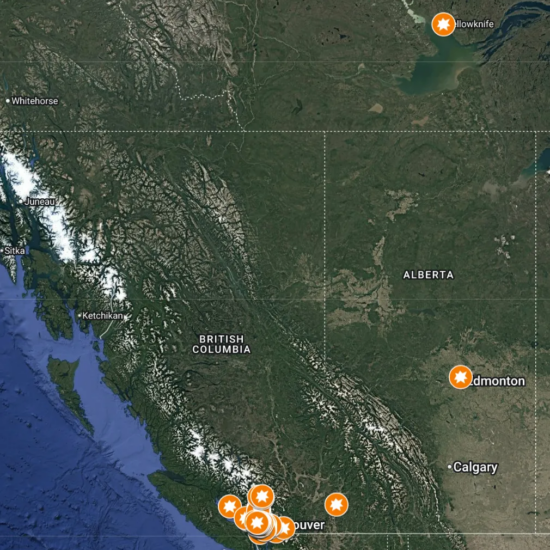

Stan Bartlett of the Grumpy Taxpayer$ of Greater Victoria took one look at the 13-page document released Aug. 16 by a group bidding to stage the 2022 Commonwealth Games in British Columbia’s capital, Vancouver and Richmond.

Above a photograph of fireworks over Victoria’s inner harbour, there are bold, capital letters that label it a “business plan.” But to Bartlett, the whole thing is smoke and mirrors.

“For starters, by no definition is this a business plan,” Bartlett told theBreaker. “Lunacy. Likely a $1.5 billion Games by the time all is said and done.”

The group, led by newspaper publisher David Black, claims it would cost $955 million — but it needs $825 million of that from taxpayers, including $298 million to build and renovate venues. The bid group also needs letters of support quickly from B.C. NDP Premier John Horgan and Liberal Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. The Commonwealth Games Federation wants bid books in by the end of September so it can decide on a replacement for stripped 2022 host Durban, South Africa in November.

The business plan dubs the group’s vision “Back to the Future” and pledges a “low cost, low risk, high impact” Games. But as Bartlett suggested, there is nothing in the document that explicitly discusses weaknesses or threats to the prospective business and how they can be mitigated or prevented.

It also does not say whether it would be the federal or the B.C. government that would be responsible for any cost overruns. When Vancouver hosted the 2010 Winter Olympics, it fell upon the provincial government, which added more taxpayers’ money to the budget before and after the 2008 recession. The Vancouver Olympics took five years to win the bid and another seven years to build and stage; by the time the new 2022 host is chosen, there will be just over four-and-a-half years to deliver. A June 27 letter by Sidney Mayor Steve Price to the Commonwealth Games Federation president Louise Martin supported the bid, based on $300 million from Sport Canada and $150 million plus “a guarantee against overruns” from the B.C. government.

In a quip less colourful than Montreal Mayor Jean Drapeau’s oft-quoted “the Olympics can no more lose money than a man can have a baby,” Black told reporters in Victoria on Aug. 16 that “there is no risk whatsoever of an overrun.”

Victoria/Vancouver/Richmond are not alone. Birmingham and Liverpool are jockeying for the United Kingdom government’s nod. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, the 1998 host, is a potential bidder. Australia, the 2018 host, may step in if other bids fail.

The Victoria-centric document — which contains several grammatical errors and is missing economic spinoff estimates and venue maps — says $42 million is needed for a new athletics and ceremonies stadium and $30 million for a gymnastics arena in suburban Langford. It also needs $35 million to renovate the Saanich Commonwealth Pool, which was built for Victoria 1994 Commonwealth Games. Temporary fencing, fixtures, facilities and equipment at venues, also known as “overlay,” would cost $87 million.

Commonwealth Games executives, foreign aristocrats, politicians and sponsors would stay in luxury at the Westin Hotel and Residences on Bear Mountain. Officials would use 1,000 beds in existing University of Victoria dormitories. A $600 million, 7,000-bed athletes’ village is proposed for Langford, to be used by students after the Games. The business plan contemplates just $60 million from taxpayers for the development.

On the surface, that is a bargain, until one considers the last time B.C. hosted a mega-event. The athletes’ village was the most troublesome venue for Vancouver’s 2010 Winter Olympics after the global credit crunch hit in fall 2008 and the developer needed a taxpayer bailout to stay on schedule. The $1.1 billion, 1,108 condo development, which included $30 million in seed money from taxpayers, was refinanced by city hall in 2009 and put into receivership eight months after the Games because of slow condo sales. It took until 2014 to pay-off the debt.

What price security?

Kris Sims, the Canadian Taxpayers’ Federation’s B.C. director, said there is also a major gap in the alleged business plan: security costs, beyond local traffic police.

British Columbians also don’t forget that it cost $900 million for an RCMP-led security blanket over the 2010 Games. There was no terrorism, but there was vandalism, protests that snarled traffic and a Latvian crime ring that bought $2 million worth of tickets with stolen credit card numbers.

“We all want to be safe, but trying to leave that out of your actual tally of how much you’re going to cost taxpayers is disingenuous,” Sims said. “Taxpayers should know how much that’s going to cost.”

Sims said major sports events should be built and operated only with private money. If not, taxpayers deserve the final say over how their money is spent. She also said mega-events tend to have fluid budgets, that always increase, and organizers that always try to claim they are under budget by moving the goalposts.

“Keep in mind what a billion dollars could pay for,” Sims said. “You could do many things, you could spend it more wisely, you could actually reduce your deficit, or you could cut taxes. Everybody needs to keep in mind this is not ‘government money,’ this is your money, my money and your neighbour’s money.”

The business plan says organizers want to integrate the Victoria Aboriginal Cultural Festival into the Games festival, complete with a lacrosse exhibition. There would also be an International Pride House, for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender athletes and supporters.

Such inclusivity is hardly a consolation for Chris Shaw. The neuroscientist was the leader of the No Games 2010 coalition and now lives in Victoria. He calls the Commonwealth Games bid premature and warns bidders to expect opposition every step of the way.

“So in this time of wildfires and other urgent needs, David Black thinks taking 400 mill [from B.C. taxpayers] for Games and fluff is a good idea?” Shaw asked.

Shaw said that by including Vancouver’s B.C. Place Stadium for rugby sevens and the Richmond Olympic Oval for table tennis and badminton, the anticipated $400 million federal contribution would have to double to pay for securing both sides of the Salish Sea. Shaw calls the $130 million estimate for TV rights and ticket sales revenue “fantasy.”

“One has to wade through 13 pages of kittens and rainbows fluff to find the core. The budget is so pathetic it makes the 2010 Bid Corp look completely professional — and this is hard for me to say,” Shaw said.

Politicians who will say yea or nay to the 2022 bid are on the fence.

Vancouver’s B.C. Place Stadium could host Commonwealth Games rugby sevens in 2022 and/or World Cup soccer in 2026. (Mackin)

CBC reported Aug. 15 that B.C. Finance Minister Carole James was “very cautious” because very few details had been provided by bidders.

“The fact [is] that the decision has to be made very shortly and there’s still not a thorough business case that has come forward,” James said.

Federal sport minister Carla Qualtrough told theBreaker on Aug. 1 that Ottawa was waiting for a formal proposal. She said Hamilton was already considering a bid for the 2030 Commonwealth Games, to celebrate a century since hosting the first edition in 1930. Canada is part of a joint bid for the 2026 FIFA World Cup with the U.S. and Mexico, and Calgary is studying a bid for the 2026 Winter Olympics.

“We have to factor in all the other things going on in sport and other requests that might come to the federal government,” Qualtrough said. “We have to look at where this all fits on on the broader national agenda for sport hosting.

“These things become expensive very quickly and the kind of expectations that an international federation, Games organization would have on any community, so we’ve got to be mindful of all of that.”

Commonwealth Games 2022 Business Plan Aug 14 2017 Wo Appendix by BobMackin on Scribd