Bob Mackin

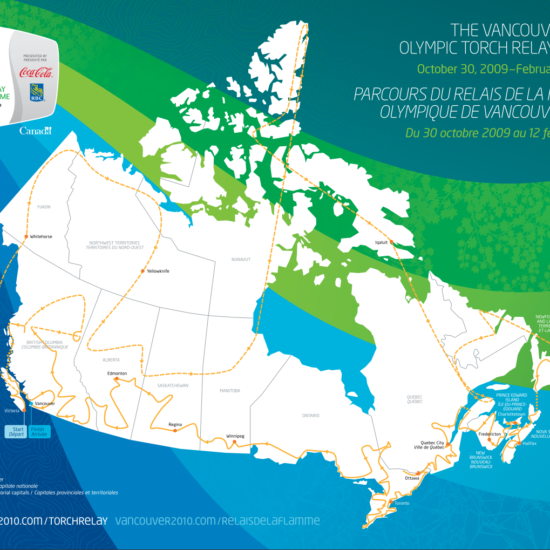

A mysterious, large, white cubic structure occupied the plaza outside the Vancouver Convention Centre’s western expansion. The location would offer a scenic backdrop for Olympic broadcasters that included a set of Olympic rings floating on a Washington Marine Group barge off Stanley Park in Coal Harbour with the North Shore mountains in the distance.

A Feb. 5, 2009 sketch from a David Atkins production meeting for the Vancouver 2010 opening ceremony (VANOC/Vancouver Archives)

An official announcement was not made, but Premier Gordon Campbell did not deny a cauldron was secretly assembled there. “I’m sure you’re going to know more about it, there’s no point in keeping it secret forever,” Campbell said when I asked a few days before the Games. “You’ll hear all sorts of great stuff about Jack Poole in the next few days and, deservedly so; these are his Olympics.”

Campbell named the plaza after Poole on October 2. Three weeks later, the developer was dead. The local CTV affiliate saw my story and sent its Chopper 9 helicopter to survey the location. The white box had no roof and CTV’s aerial footage showed an industrial burner below. VANOC executives were not amused.

VANOC CEO John Furlong showed his displeasure with CTV by doing an exclusive interview with competitor Global TV in which he tried to douse rumours that Wayne Gretzky would be the final torchbearer.

“You can think about the last moments of the ceremonies as long as you’d like and you’re not going to figure it out,” Furlong said.

When it came time for those last moments, Wayne Gretzky, Steve Nash, Catriona Le May Doan and Nancy Greene Raine were waiting to light their torches and then the indoor cauldron. Four ice poles were supposed to rise from the false floor like the four totem poles did earlier, and rest on each other with a single shaft emerging from the centre.

Exactly two months earlier when the torch relay went through Ottawa, Furlong had secretly invited Greene Raine, the Canadian Press female athlete of the 20th century and a Conservative senator. She didn’t know who else would be in that final group until their secret rehearsal on February 10.

“The rehearsals went pretty well, we were confident, we knew the torches had only so much gas in them and everything was scripted,” Greene Raine said. “We had earphones in our ear and we were taking directions from David Atkins. He was so calm.”

Three of the shafts emerged and so did the centre burner. But not the one nearest Le May Doan.

Three of the shafts emerged and so did the centre burner. But not the one nearest Le May Doan.

“Athletes, hold your position, we have a glitch,” Atkins said. “We’re having trouble with Catriona’s leg coming up.” “We stood there for what seemed like an eternity, we could hear him saying ‘try this, try that’ to all the people in behind, underneath the stage,” Greene Raine said.

“Catriona your leg’s not coming up, your role now is to salute the VIP box,” Atkins said. “Everybody else, in 10 seconds I’ll count you down and carry on.”

“Then we did,” said Greene Raine. “When we walked off there wasn’t 20 seconds left of gas.”

A $20 encoder failed, one trap door stayed shut. Le May Doan had nothing to light. After awkward silence, the other three did their duty.

Gretzky worked overtime. He was shuffled out of the stadium and into a waiting white pickup truck with green and blue trim for the drive to Jack Poole Plaza while holding the last, lit torch. The giant, white box beside the Vancouver Convention Centre had been removed, revealing the permanent replica of the indoor cauldron that Gordon Campbell failed to keep secret.

Despite what Furlong said the previous day, Gretzky was the last torchbearer after all.

Games on!

The company that engineered both the indoor and outdoor cauldrons had the foresight to prepare for a malfunction.

“If nothing had been done there would have been gas coming out (of the fourth arm),” said Con Manias, president of Sydney, Australia-based industrial and ceremonial burner specialist FCT Flames. “We had considered the possibility of perhaps not being able to operate one of the arms for one reason or another. It required our technicians to be able to make some changes to the gas systems to allow the three arms to operate in isolation.”

Had the Olympic flame gone out of control, it could have been the biggest disaster in Olympic history.

Neither VANOC nor B.C. Place had conducted a fire drill for more than two years in the stadium. Minutes of the stadium’s March 5, 2010, Joint Occupational Health and Safety Committee said VANOC did a bell test, but no evacuation simulation. Provincial workplace safety law requires one every year.

“This test needs to be conducted,” said the meeting minutes. “The employer is in violation.”

Despite claiming to be a “green” Games, the permanent, outdoor Olympic cauldron and the one used at the B.C. Place ceremonies consumed 5,260 Gigajoules of natural gas at Games time. That would have heated 65 British Columbia households for an entire year.

An excerpt from Red Mittens & Red Ink: The Vancouver Olympics e-book, by Bob Mackin. Click here to get your copy today.

Support theBreaker.news for as low as $2 a month on Patreon. Find out how. Click here.