Bob Mackin

A vice-president of the union that represents B.C. paramedics says the province needs more than new emergency management legislation and updated guides on how to plan for the worst in a world that gets more dangerous.

November 2021 RCMP CBRNE exercise at B.C. Place Stadium (BC RCMP)

The “Lessons Learned” report on how the NDP government handled the pandemic emergency was critical of the province for abandoning the emergency management approach. The three co-authors found the government switched gears early in the pandemic, in favour of government coordination and the healthcare system.

“It was replaced by an executive decision-making model more familiar to senior government leaders, as happened in many other jurisdictions. The result was effective crisis decision-making but not effective cross-government response coordination,” said the report, which the government concealed for nine weeks before its Dec. 2 publication.

The report said that government should consider developing a new approach to plan for province-wide emergencies “that includes much more than a plan for how government will be coordinated, including risk identification, developing, practising, and continuously improving plans for major emergencies.”

Dave Deines with the Ambulance Paramedics and Emergency Dispatchers of B.C. said planning and policies can only go so far when staffing is inadequate. That became obvious during 2021’s heat dome and atmospheric river disasters.

“Even if the ambulance service was staffed at 100%, during those environmental emergencies, we still would have been taxed and unable to respond,” Deines said in an interview. “But the reality is, when that happened, you had, in some cases, 30 or 33% of the fleet was not staffed, which, again, is just compounding these issues over and over and over until we almost saw near complete collapse of the paramedic service in British Columbia during the heat dome.”

While the government readies the new law for the new year, a legacy of security planning for the Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympics is already needing an update, after a year that included threats by Russia to use nuclear arms in the Ukraine war and the perennial threats by North Korea to fire a missile across the Pacific Ocean.

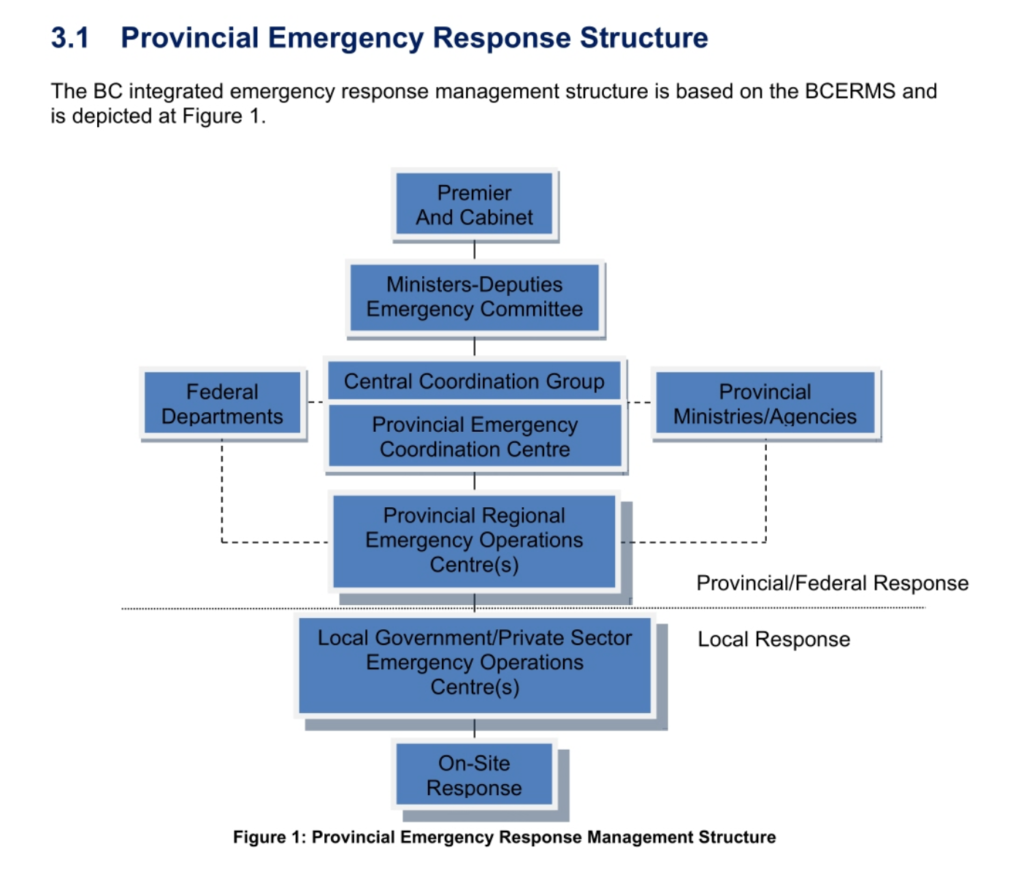

From B.C. CBRNE Plan (BC Gov)

The B.C. Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear and Explosives [CBRNE] Response Plan, obtained under freedom of information, is a 50-page guide on preparation, prevention, response and recovery should an accident occur or a terrorist attack the province.

Written in 2009, the plan cites 9/11 and 1995’s Tokyo Subway nerve agent attack and the Oklahoma City bombing as examples of CBRNE incidents. It contemplates potential incidents and remedies for each of the five categories, but concedes response would be difficult.

“In most scenarios, there is a possibility of overwhelming the health facilities due to casualties, contamination and public concern (i.e. psychosocial effects) and this should be considered as a potential consequence in any CBRNE event,” the guide states.

The province is responsible for preparedness and development of capabilities to respond to a CBRNE attack, in conjunction with local, regional and national agencies.

From B.C. CBRNE Plan (BC Gov)

“It’s not just Ukraine,” Deines said. “I mean, on a daily basis, the amount of hazardous materials, including radioactive materials and transit through British Columbia, and across Canada, for that matter. People really have no idea how much is going through the country, but, at any time, there’s potential for catastrophic dispersal of those hazardous materials.”

A related blueprint, called the B.C. Nuclear Emergency Plan [NEP], was signed-off by Provincial Health Officer Dr. Bonnie Henry and Deputy Health Minister Stephen Brown while politicians were away from the Legislature during the 2020 snap provincial election.

The 71-page guide said that the risk of a nuclear emergency in B.C. is low, but acknowledged a need to prepare for such an event and to regularly update planning, based on lessons learned.

The plan is designed for accidental or unintentional events, but elements may be used to address the consequences of deliberate or malicious acts. In that sense, it is a bookend to the CBRNE plan.

The NEP ranks potential incidents in five categories, including emergencies at nuclear power plants in Canada, U.S. or Mexico, a nuclear powered vessel in Canada, and other nuclear emergencies inside and outside North America.

The nearest nuclear plant is some 400 kilometres south of B.C. in Richland, Wash., while there are particle accelerators at the University of B.C.’s TRIUMF and Redlen Technologies in Saanichton.

In the case of a nuclear emergency outside North America, the NEP assumes small quantities of radioactive material, if any, would be expected to reach Canada (as happened after the 1986 Chernobyl and 2011 Fukushima disasters) and would likely not pose a risk to health, safety, property or the environment. The main focus for authorities would be Canadians living or traveling in the affected region and control of food and material imports into Canada from the affected areas.

In November 2021, the RCMP’s CBRNE team held a three-day, joint training exercise with military, fire, police and federal and provincial public health officials, but not B.C. Emergency Health Services. One of the scenarios was a simulated mass casualty attack at B.C. Place Stadium.

The next exercise to be led by B.C.’s Ministry of Emergency Management and Climate Readiness is scheduled for February 2023, but Exercise Coastal Response is an earthquake simulation.

Deines said B.C. Ambulance Service had a robust CBRNE team that was disbanded when Provincial Health Services Agency took over the service a decade ago. CBRNE training is now on an ad hoc basis.

“It becomes a real Catch-22 of how do we train to prepare for an event when we can’t respond to the core business right now?”

Support theBreaker.news for as low as $2 a month on Patreon. Find out how. Click here.