Bob Mackin

Peter German, the former senior Mountie who wrote the book on money laundering in Canada, released his review of money laundering in Metro Vancouver casinos on June 27.

German estimated more than $100 million has been laundered through Metro Vancouver casinos. His 247-page “Dirty Money” report included 48 recommendations and relied on 160 interviews with people in law enforcement, academia and the industry itself. He also noted the work of various media outlets, including CBC, Globe and Mail, Vancouver Sun and theBreaker. “A free press and strong, ethical investigative journalism is critical to the rule of law,” German said.

German has urged the NDP B.C. government to build a new, independent regulator of gambling in B.C. and start a dedicated casino police force.

theBreaker read German’s report and found these 14 highlights (with the paragraph number from the report, arranged under headings by theBreaker) that will blow your mind about various degrees of rampant incompetence and corruption in British Columbia.

The Vancouver model, explained

Peter German’s Dirty Money report was released June 27 (Mackin)

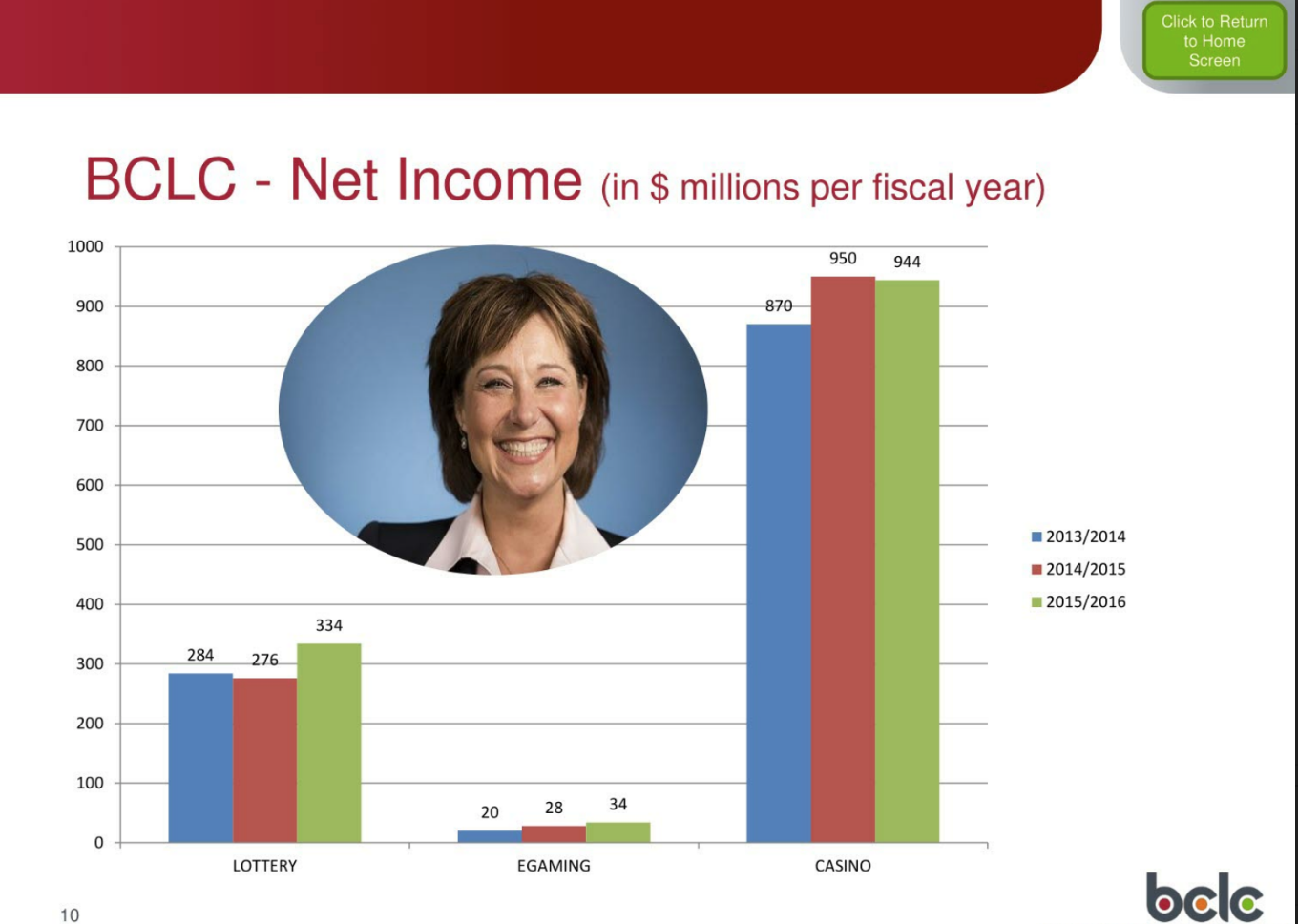

In the Vancouver Model, Chinese citizens wish to relocate some of their wealth from China to Canada. To do so, they agree to accept cash in Canada from a lender. At that point, a settling of accounts occurs, app to app, between the person making the loan and an underground banker in China. The catch is that the provenance of the cash loaned in Canada is unclear. It generally comes in the form of stacks of $20 bills, wrapped in a fashion that more closely resembles drug proceeds than it does cash originating at a financial institution. The Chinese individual will then buy-in at a casino with the cash, gamble, and either receive higher denomination bills or a cheque upon leaving the casino. The lender is both servicing a drug trafficking organization by laundering its money, and the Chinese gambler by providing him or her with Canadian cash.

[Prof. John] Langdale’s research indicates that Vancouver is a hub for Chinese based organized crime. A complex network of criminal alliances has coalesced with underground banks at its centre. Money is laundered from Vancouver into and out of China and to other locations, including Mexico and Colombia. Illegal drug networks in North America are supplied by methamphetamines and precursor chemicals from China and cocaine from Latin America. In addition, “high rollers” from China facilitate the flight of capital from China using Canadian casinos, junket operators and investment in Canadian real estate. (from paragraph 126)

RCMP report on loan sharking

In January 2009, an RCMP report was prepared on the extent and scope of illegal gaming in B.C. The report was prepared from data for the years 2005 to 2008. It included the following in its executive summary:

“…during the three-year research period there were four murders and one attempted murder of people who had some involving in gaming. Forty-seven individuals have been identified in suspected loan sharking activities.”

Coleman (Mackin)

The 47 individuals believed to be involved in loan sharking included go-betweens or runners. It noted that besides lending money at a criminal rate of interest, loan sharks can be involved in money laundering and extortion. Many victims are reluctant to call the police while others may contact the police as a means of buying time from the loan shark.

The report noted that in 2009 there were at last (sic) seven significant loan sharking rings operating in the Lower Mainland, including family operations. Some were believed to be involved with known organized crime groups. The report noted that loan sharking can be a very lucrative business, judging by one loan shark owning a house valued at over $2 million.

The report also quoted from a June 2009 national RCMp report on the vulnerability of casinos to money laundering an organized crime. (189)

The new BC Liberal euphemism

By spring 2004, the new model was in place. Through a franchise arrangement, revenue to the government could be doubled. The regulator remained in government but was placed under an [Assistant Deputy Minister]. ‘Problem gambling’ was renamed as ‘responsible gambling.’ (227)

IIGET goes

Although it was given an additional year, government was not satisfied that [Integrated Illegal Gaming Enforcement Team] was providing value for money. On March 31, 2009, it was disbanded, thereby ending direct, focused police involvement in gaming within B.C. Although the team had made inroads into illegal gaming, the prevailing view in government was that the results did not justify the expenditure. From this point forward, police involvement within casinos occurred, either through calls for service to the police force of jurisdiction, or by the RCMP’s proceeds of crime unit, discussed later.

To this day, there is debate about the effectiveness of IIGET. Some have complained that it failed to achieve its objectives. Others point to resourcing problems. Some members complained that they did not receive significant training in this specialized area. The fact that IIGET did not bring in partners was a reason given more recently by the RCMP. The absence of Vancouver Police members was seen as an impediment due to the number of illegal gaming complaints, which originated in the city.

The abolition of IIGET came despite the consultative board receiving a report two months earlier from the RCMP, which dealt with the extent and scope of illegal gaming in B.C. The report was requested by IIGET and was prepared from data for the years 2005 to 2008…

The report noted that 284 gaming incidents were reported during the three years, of which 183 involved illegal common gaming houses. Twenty-five reports involved common gaming houses operated by organized crime figures or frequented by gang members. Two were the scenes of murder or attempted murder. Children were abducted from one gaming house to force the payment of a debt. (412)

Elsewhere in Richmond

A GPEB investigator reported that in September 2010, a patron entered the Starlight casino with $3.1 million, of which $2.6 million was in $20 denominations, bundled in bricks of $10,000, wrapped with an elastic band at either end and carried in inexpensive plastic bags. The same patron made numerous other buy-ins, always with used currency. Sometimes he left the casino and returned minutes later with another bag of cash. He was known to associate with individuals who had previously been involved in loan sharking. (433)

All tickety-boo

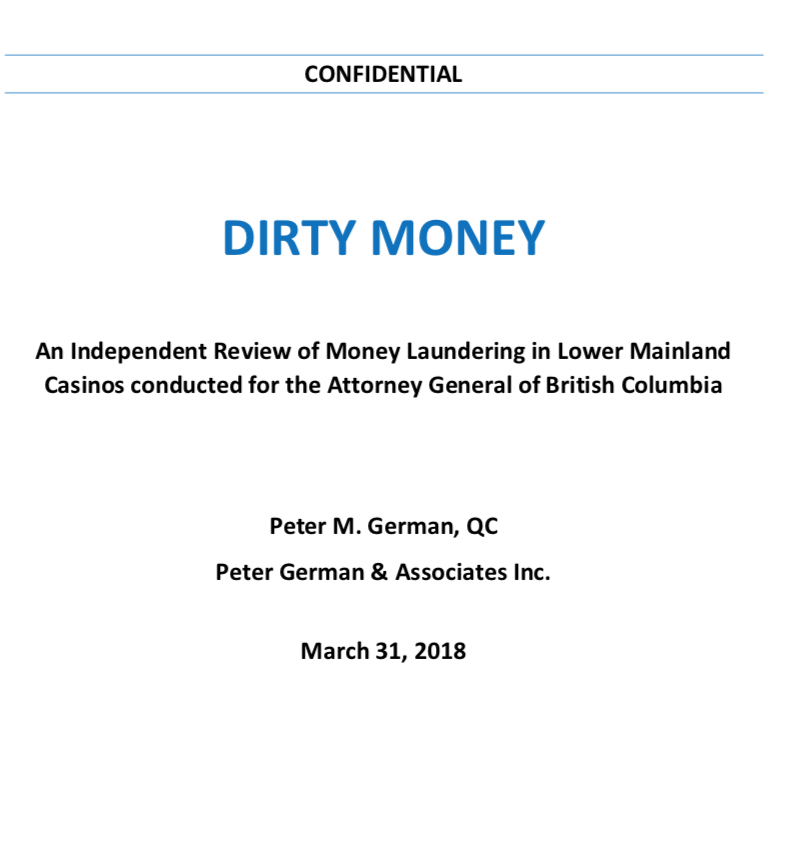

BCLC lottery vs. casino profits chart, showing Christy Clark, from BCLC’s Rolling the Dice presentation (BCLC FOI)

April 2014, new GM requested organizational review of GPEB, conducted by Corporate Services in Ministry of Finance and completed on Sept. 18, 2014. Briefing notes to the minister indicate the purpose was to “support the ongoing success of GPEB…” and to “determine how GPEB programs and services can best be aligned, integrated and delivered to ensure the integrity of gaming.” The minister was apparently not advised in writing of the ongoing problems within GPEB. (509)

Money Laundering Summit

On June 4, 2015, BCLC, GPEB, FinTRAC, [Canada Revenue Agency], [Canada Border Services Agency] and RCMP officials met together at BCLC’s Vancouver offices for a workshop, entitled “Exploring Common Ground, Building Solutions.” This has been referred to as the “Money Laundering Summit.” The rhetorical questions asked of participants was, is there a problem? The general consensus – yes. BCLC investigators assured the police that after conducting two to three weeks of surveillance on suspected money launderers, the police would be able to locate the “money house.”

The RCMP appears to have taken up this challenge. On July 22, 2015, [Federal Serious and Organized Crime] officer advised a BCLC investigator that they had found “Pandora’s Box” the previous evening. The RCMP officer added that some of the money may be going offshore to fund terrorism. The BCLC investigator immediately notified senior managers at BCLC. The investigator also notified GPEB.

Once the police became engaged, BCLC investigators provided support in what BCLC termed a “great relationship.” In addition, the River Rock provided “enormous” support when requested by police, often on short notice.

Curiously, the regulator seems not to have been involved in this effort until notified by BCLC. According to BCLC investigators, GPEB was “the biggest part of the problem.” Clearly the relationship between investigative arms of the two entities had deteriorated, but the Executive Director of the new compliance division at GPEB made it his mission to remedy the situation. (532)

Strained or broken? That is the question

Relationships between BCLC and GPEB are at best, strained; and at worst, broken. The issues tend to be most pronounced at the management level and within the compliance and enforcement areas. This is not new and has been ongoing for a decade. It is also not universal, as many people in both organizations work well together, but it is a general observation which was repeated in dozens of interviews…

GPEB investigators face many obstacles. They do not have on-site or office access to the iTRAK system which contains all GSP report and the BCLC investigative summaries. GPEB is allowed access to two iTRAK computers at the BCLC offices in Burnaby, which is a relatively unworkable arrangement considering the logistics of driving to BCLC’s offices simply to use a computer. A former casino executive described GPEB “always [being] pushed to the side,” with “no instant access to information.” (610)

BCLC goes undercover, RCMP not amused

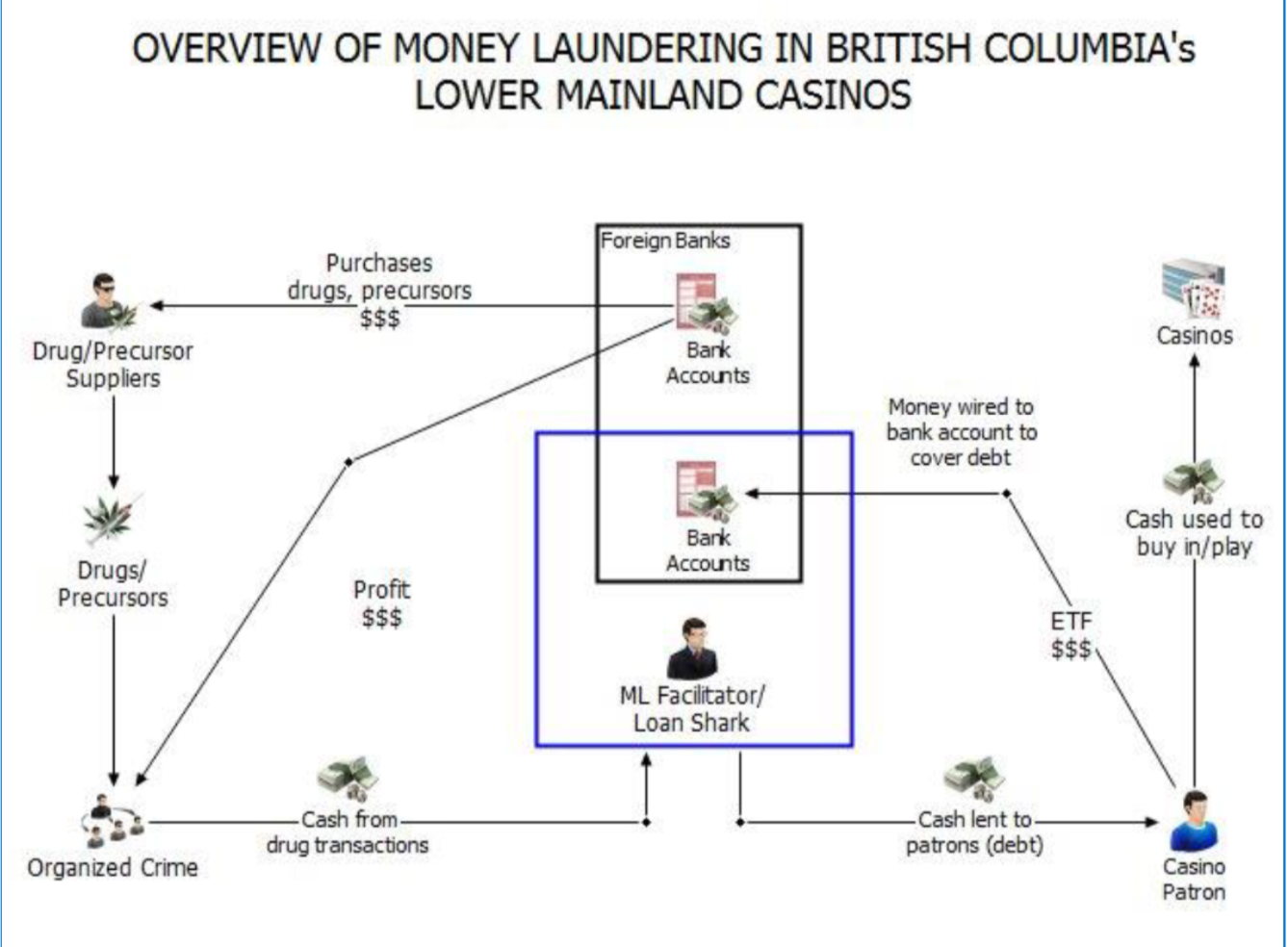

source: Dirty Money by Peter German (2018)

BCLC’s AML unit has involved itself in undercover operations. One such operation was a form of ethics/value testing at [Money Service Bureaus] in the core financial district of Richmond. The genesis of the operation was information obtained by BCLC from patron interviews, which indicated that clients could obtain better interest rates at some Richmond MSBs by accepting small denomination bills during money exchange transactions. BCLC decide to test this information as part of its enhanced due diligence, AML program. The intent appears to have been an attempt to determine if local MSBs were dispensing the proceeds of crime, in the form of $20 bills, to customers.

A BCLC employee entered various MSBs, on the pretext of having a family member who wished to wire money from China to Canada. The employee made a record of the responses obtained to various questions. Among the MSBs targeted was one of Canada’s largest foreign exchange companies… The RCMP became aware of the operation. It cautioned BCLC that performing an undercover scenario in these circumstances, which may appear relatively innocent, can have unforeseen circumstances. Without training in undercover operations, there is always a danger of discovery, leading to concern for an operator’s personal safety. Without deconfliction, BCLC could also be interfering with an ongoing police investigation. (633)

“Education session”

On Nov. 27, 2015, BCLC’s AML unit sent memo to the head of compliance noting that BCLC had previously supplied a list of 16 individuals, all known patrons of the River Rock, who had been flagged by BCLC “due to suspicious behaviour involving casino financial transactions.” In accordance with policy, GCGC was asked to “conduct an education session” with 14 of the players.

The purpose of the education sessions was to notify the patrons that their buy-ins were being monitored and that their source of funds was of concern… (640)

FinTRAC fine

BCLC became the first provincial gaming corporation to be sanctioned by FinTRAC. On June 15, 2010, FinTRAC issued a Notice of Violation alleging that BCLC was non-compliant with the [Proceeds of Crime, Money Laundering, and Terrorist Financing Act] because of filing delays, inadequate information and other deficiencies identified in more than 1,285 reports. According to FinTRAC, BCLC’s systems had been reporting incorrectly for years. The difficulties were exacerbated when casino disbursement reports were add to the list of reportable items on Sept. 29, 2009. The penalty was fixed at $670,000. (656)

BCLC’s bungled software buy

SAS is clear that “the software was not proven in the casino industry” and this “presented risk from a technical, budget and timing perspective.” SAS candidly admits that many challenges arose during the project, for which responsibility has yet to be assessed. Contrary to the advice received from BCLC, the CDR issue was one of many, as follows:

- Misalignment on the degree to which SAS AML could integrate with the existing iTRAK system

- Data quality issues

- Underestimation of the customization effort required to develop FinTRAC reports, especially casino disbursement reports

- Poor scope management, especially relating to system requirements and design changes

- Resourcing challenges

- Questionable testing methodology and processes that may not have adequately included system end users. (712)

Host with the most

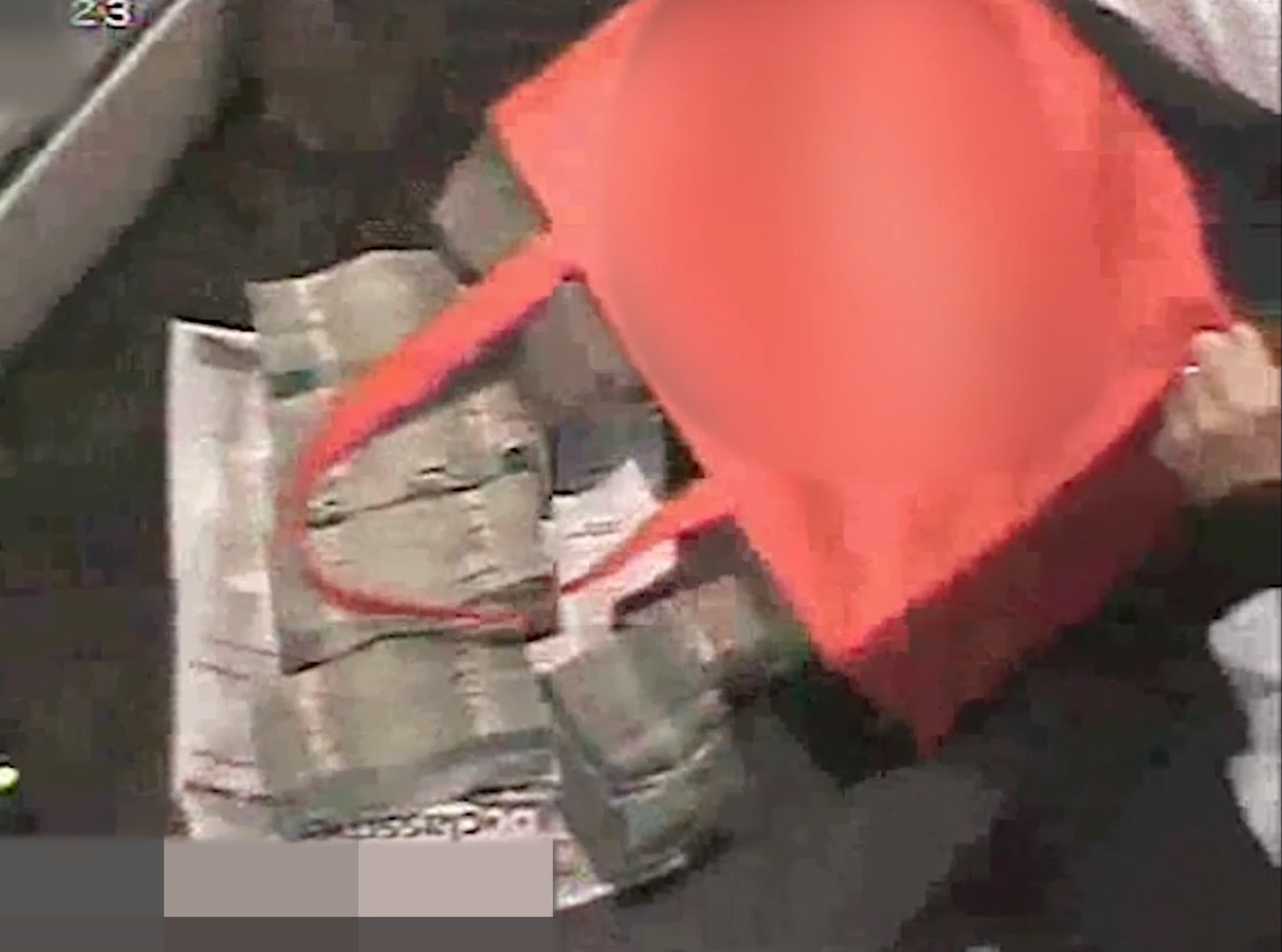

A bag of cash from a surveillance video at Starlight Casino (BC Gov)

In one case, a VIP host allegedly arranged a buy-in of $200,000 in $100 bills for a person who was representing a high limit player, banned from the casino for inappropriate behaviour. Apparently the intent of the buy-in was to obtain chips in advance of a visit from China by four friends of the banned player. The host allegedly facilitated the purchase and provided a River Rock bag to assist the third party transport the chips out of the casino.

[Great Canadian Gaming’s] surveillance team at River Rock observed the transaction, and reported it to BCLC as [Unusual Financial Transaction]. This was done because the patron left the casino with no play, which is a strong indicator of a possible third-party transaction. (738)

Betting with bitcoin

Despite cryptocurrency not currently being offered as a casino cash alternative, it is quite likely that it is being used outside casinos to settle loans and other debts. Vancouver lawyer Christine Duhaime is quoted as noticing “recently that bitcoin has become a big way to move money out of China,” noting that it is “instantaneous and no one knows at either end.”

FinTRAC asserts that cryptocurrency exchanges are MSBs and therefore subject to the normal AML requirements. However, no cryptocurrency exchanges are currently reporting to FinTRAC. (787)

Support theBreaker.news for as low as $2 a month on Patreon. Find out how. Click here.