Bob Mackin

A critic of the British Columbia coastal salmon farming industry says the latest efforts by two major players to fight sea lice are all for show.

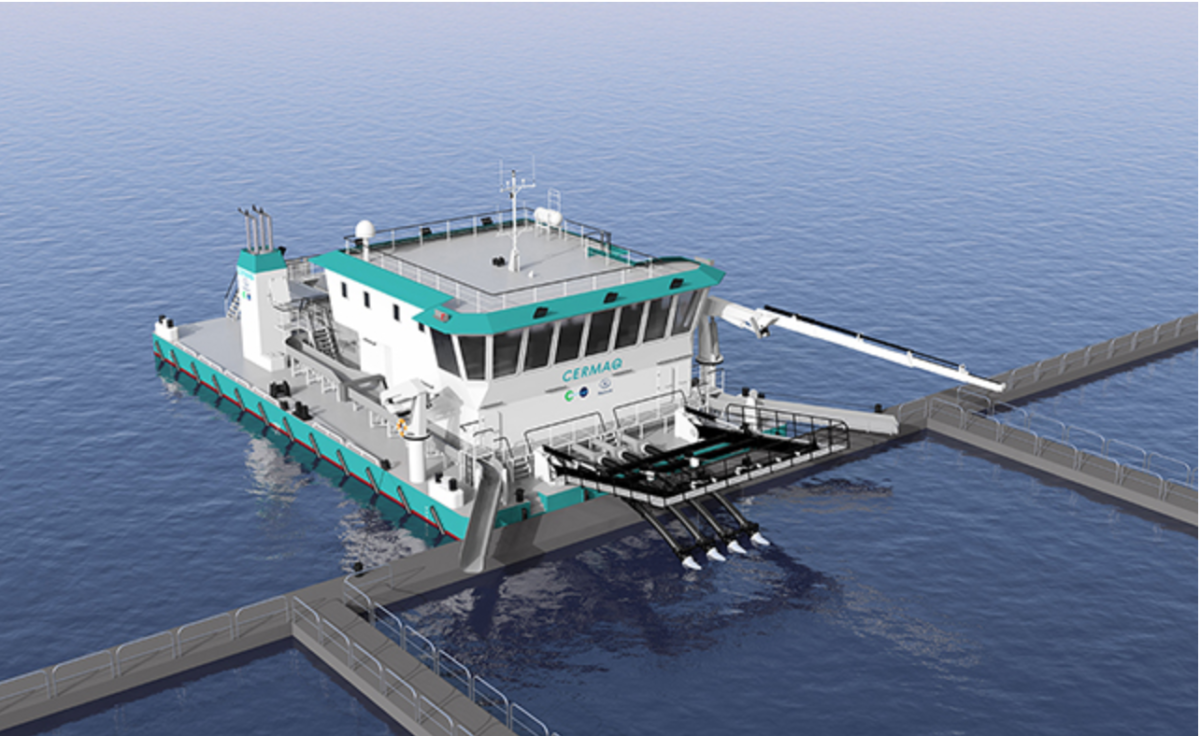

Biologist Alexandra Morton says Cermaq’s $12 million hydrolicer barge and MOWI’s $30 million delousing ship Aqua Tromoy failed to make a difference in Scandinavia and they won’t make a difference on Canada’s West Coast.

Cermaq’s hydrolicer barge (Cermaq Canada)

“They’re saying it’s a one billion [dollar] with a b problem, and they don’t know how to stop it, they don’t know how to control the lice,” Morton said in an interview. “This is the equipment in Norway that didn’t work, they’re sending it here to make it look like they’re diligent and spending a lot of money.”

Morton quoted a June story in trade publication IntraFish that said sea lice costs the industry close to $1 billion a year. The IntraFish story quoted MOWI Southern Norway production manager Bernhard Ostebovok’s concession: “We must admit that the louse is there and will always be there. As long as we farm in open cages in the sea, we must live with lice.”

IntraFish’s latest detailed sea lice report said B.C. produces two-thirds of Canada’s farmed salmon, mostly Atlantic salmon, and mentioned the spring 2018 major sea lice outbreak in Clayoquot Sound that affected both farmed and wild juvenile salmon.

Alexandra Morton (Rolf Hicker/Facebook)

Cermaq spokeswoman Amy Jonsson said the company is “excited” about the custom built barge for imminent use at farm sites around Tofino. The purpose-built hydrolicer barge uses no medication or pesticide. For a farm of up to a million fish, it takes two to three days to delouse them all.

Jonsson said Cermaq is seeing very low numbers of sea lice at farms in Clayoquot Sound. Fish were treated as smolts with Lufenuron, the active ingredient of flea medication for dogs and cats. Lufenuron is only available through a case-by-case, emergency drug release permit from the Veterinarian Drug Directorate of Health Canada. It protects salmon for six to 10 months and is administered in freshwater hatcheries.

MOWI did not respond.

The industry is facing political pressure, but Morton is not sure how effective it will be after meeting with Fisheries and Oceans Minister Jonathan Wilkinson in early June.

“He wants to do these things, but he has no idea what he’s up against with his senior bureaucracy, particularly in the aquaculture management division,” Morton said. “They work with the aquaculture industry, the aquaculture management division of DFO, their master really is the aquaculture industry.”

Smolt with lice (Salmon Confidential)

Wilkinson appeared July 10 by the site of the 2014 Seymour River rockslide, where a salmon run is being restored. He told reporters that he wanted to “move this conversation about aquaculture beyond this almost futile debate that’s been going on the last number of decades.”

“We will be more fully implementing the precautionary principle, more area-based management, moving farms away from areas of wild salmon migration,” he said. “We’ve required now testing a range of viruses that were not required to be tested before. We have said, in part as a result of the conversation I had with Alexandra, that we will be more forcefully enforcing the regulations with respect to sea lice going forward.”

Wilkinson said that the way conditions of licence had been constructed for some farmers, DFO had difficulty enforcing regulations.

Fisheries and Oceans Minister Jonathan Wilkinson on July 10 (Mackin)

“We will be changing that to make sure we can enforce that on a go forward basis and make sure that they are in compliance with all the regulations.”

Morton and others, however, have long advocated for shutting down the open net farm system and moving to land-based fish farms.

In Washington State, coastal fish farms will be banned by 2022 from raising non-native fish. The decision came after a Cooke Aquaculture net pen containing 305,000 Atlantic salmon collapsed in summer 2017 near Cypress Island. An estimated 243,000 to 263,000 fish escaped, of which 57,000 were recovered. Between 186,000 and 206,000 remained unaccounted for as of the January 2018 report.

Cooke Aquaculture originally blamed tides related to the solar eclipse, but a state report said the Aug. 21 event did not alter the normal pattern of seasonal tidal strength.

The report blamed insufficient cleaning that led to excessive bio fuelling by mussels and other marine organisms and caused breakdowns in net cleaning machines. Ultimately, on Aug. 19, “some combination of anchor dragging, failure of mooring attachment points, and failure of structural members of the net pen framing resulted in the collapse of the net pen.”

Updated permits require increased underwater video monitoring, regular inspections of net pen structures, better maintenance and cleaning, and site-specific escape response plans.

Support theBreaker.news for as low as $2 a month on Patreon. Find out how. Click here.