Bob Mackin

(Editor’s note: This is part two of a joint investigation with CTV News Vancouver. Click here for part one. )

On April 19, a month and a day after he declared British Columbia’s pandemic state of emergency, Solicitor General Mike Farnworth stood at the podium in the Vancouver cabinet office at Canada Place.

The province was struggling with overlapping health and economic crises. On the first Sunday morning after Easter, Farnworth was finally getting tough on profiteering and hoarding.

“Effective immediately, the province is enabling police to issue $2,000 violation tickets for these shameful practices, for price gouging and the reselling of medical supplies and other essential goods during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic,” Farnworth said.

Mike Farnworth announces $2,000 fines on April 19 for price gouging and reselling essential goods. (BC Gov)

All law enforcement officers, even park rangers, were empowered to write tickets. Consumer Protection B.C., an agency spun-off from government in 2004, was tasked to investigate and refer evidence of wrongdoing to the Solicitor General’s ministry.

Social media scenes of panic-buying for toilet paper and cleaning supplies at big box stores in February had given way to images of empty shelves in March.

Now it was the latter half of April and unemployment was setting records. What took Farnworth so long?

On April 19, he said he was concerned “over the worst segments of society taking advantage of the most vulnerable.”

“I can assure you, we will not allow these practices to continue,” Farnworth vowed.

Through a freedom of information request, theBreaker.news obtained details of 2,065 complaints received by CPBC from March 1 to May 14.

In a joint investigation, theBreaker.news and David Molko of CTV News Vancouver have learned that more than two months since Farnworth’s order, CPBC had referred only 52 complaints to a bureaucrat in Victoria, who is refusing to talk to reporters.

A Richmond WeChat user advertised N95 masks, goggles, gloves and clothing while supplies were low at B.C. hospitals in April. (Consumer Protection BC)

A ministry spokesman said on June 22 that no violation tickets had been issued so far and information regarding the number of violation tickets issued by other agencies was unavailable. Jason Watson said some of the cases are still active, but the government’s COVID-19 Provincial Orders Support Team “has achieved compliance through education and verbal warnings” on some files.

Looking back, Farnworth said the objective was to educate the public and industry that there is an avenue to make complaints and that there are consequences for profiteering in a pandemic.

He deflected a question about the lack of violation tickets.

“It’s not something that I, as minister, [say] you shall do this, or you shall not do that,” Farnworth said June 22. “In terms of whether someone is prosecuted — that is done independently.”

Farnworth’s ministerial order was titled a “Prohibition on Unconscionable Prices for Essential Goods and Supplies.”

What is an unconscionable price? The official NDP government definition is a price that grossly exceeds the price at which similar essential goods and supplies are available in similar transactions to similar consumers.

Farnworth opted for that vague definition, rather than use a clause of the Emergency Program Act to fix prices and set rations.

By contrast, California’s law is clear.

Its statewide, anti-price gouging statute bans hiking prices of many consumer goods and services by more than 10% during a declared emergency. It applies to food, lodging and emergency supplies, including water, toiletries and medical supplies.

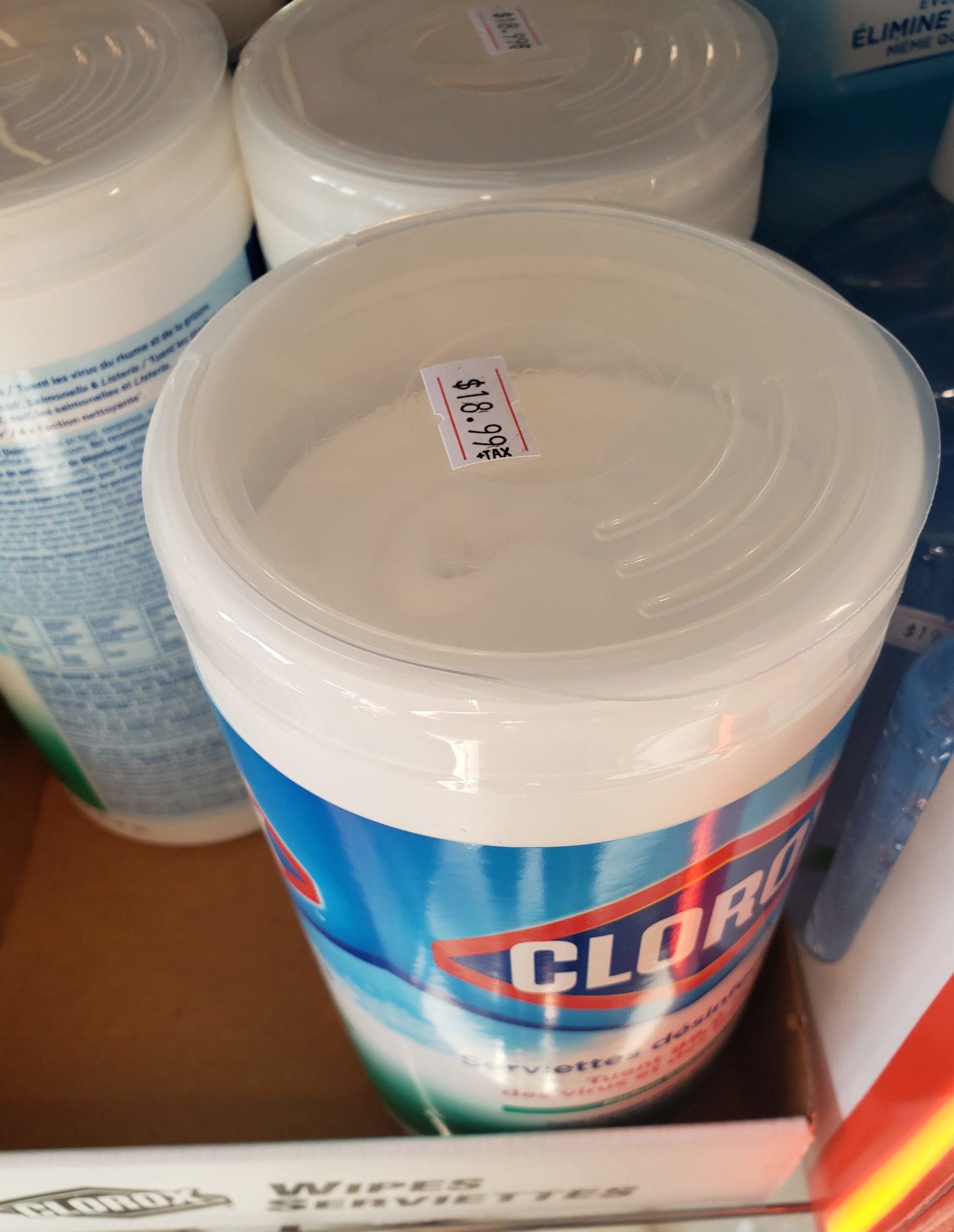

Clorox wipes for $18.99 at Dank Mart on Main Street in Vancouver (Consumer Protection BC)

David Hardisty, a marketing and behavioural science professor at the University of B.C., told CTV News Vancouver reporter David Molko that price gouging is not always black and white.

“It’ll feel like price gouging whenever you think you’re paying too much for something that may not actually always be price gouging though,” Hardisty said. “Maybe masks are in short supply for everyone, so they had to pay a lot more to get those masks. Price gouging only technically applies to necessities.”

If only a small number of stores face enforcement, Hardisty said, “it tells you, one, people are upset about the increase in prices, but, two, they’re not clear on what the rules or expectations are — what the laws are about price gouging. If people are complaining and it’s not being upheld, it’d say maybe the government hasn’t done a good job about being clear about what is what isn’t price gouging.”

In Alberta, officials had forwarded 351 of 458 complaints to investigators by May 8, the same day the government announced that its consumer investigations unit charged a Calgary business, CCA Logistics Ltd. (doing business as Newsway) for price gouging.

After a tip to the “report a ripoff” line, investigators initially ordered CCA on April 15 to drop its prices for 3M masks, hand sanitizer and Lysol spray. Some of the goods were allegedly marked up 200% to 400%.

CCA now faces a court hearing on Aug. 19. Alberta’s maximum fine is $300,000. CCA owner Yan Gong, who is also president of the Chinese Real Estate Professionals Association of Alberta, has vowed to fight the charges.

Jug of milk for $12.48 at the Real Canadian Superstore in Kamloops (Consumer Protection B.C.)

In Washington, Attorney General spokeswoman Brionna Aho said 1,214 complaints were received. Officials made 80 calls and 396 visits to businesses, sent eight warning letters and 14 cease and desist letters. Courts can impose penalties up to $2,000 per violation of the Consumer Protection Act.

“We have a longstanding policy against commenting on pending investigations, including confirming whether or not they exist,” Aho said.

By June 17, Ontario’s government had forwarded 900 of the most-egregious cases of price gouging to police around the province. Government and Consumer Services spokeswoman Barbara Hanson said the government received more than 26,000 complaints and inquiries.

B.C. is an outlier, where the government trusts consumer protection to an arm’s length agency where compliance, not enforcement, is job one.

Says the Consumer Protection B.C. website: “Our goal is not to punish a business, but rather to correct marketplace behaviour.”

Price gouging became a sudden priority for CPBC with the pandemic.

CPBC was spun out of government in 2004. It is responsible for administering the Business Practices and Consumer Protection Act and regulating the funeral industry, movie exhibitors and event ticket sellers. CPBC also licenses companies involved in payday loans, telemarketing, travel agencies and home inspectors.

At the end of 2019, CPBC had 45 full-time staff and ran on a $6.8 million budget, funded mainly by licensing fees. The five-member board is chaired by ex-BC Ferries chair Rod Dewar.

Spokeswoman Tatiana Chabeaux-Smith conceded CPBC is a small organization with relatively low public awareness, but the pandemic is an opportunity to change that. She said CPBC received 1,500 complaints before Farnworth’s order and more than 800 since.

Logo for the B.C. government’s 2004-created not-for-profit retail regulator.

“With the announcement of the ministerial order on April 19, that also elevated our profile as the place to come,” Chabeaux-Smith said.

Bruce Cran, president of the Consumers’ Association of Canada, told theBreaker.news that it has “been really horrific” since the BC Liberals got rid of the consumer protection office in the government and created CPBC 16 years ago.

“Why do they call themselves the Consumer Protection branch? The way they operate, it’s a business structure that keeps businesses from getting too many complaints,” Cran said. “They must have a giant rug somewhere where they sweep all these things underneath.”

Consumers Association of Canada president Bruce Cran (CAC)

He said unhappy consumers have even contacted him upon referral from CPBC.

“We are not the enforcement arm,” said Chabeaux-Smith. “But that our job is to intake and assess and try to get that voluntary compliance, and then when we can’t we provide a referral to government and they take that and review it and assess it and one of their enforcement officers takes it from there.”

The deregulation-minded BC Liberals came to power in 2001 by winning all but two seats in the Legislature. Their platform promised to cut B.C.’s red tape and regulatory burden by one-third within three years.

In early 2003, the Gordon Campbell-led government consulted public and industry about overhauling consumer laws.

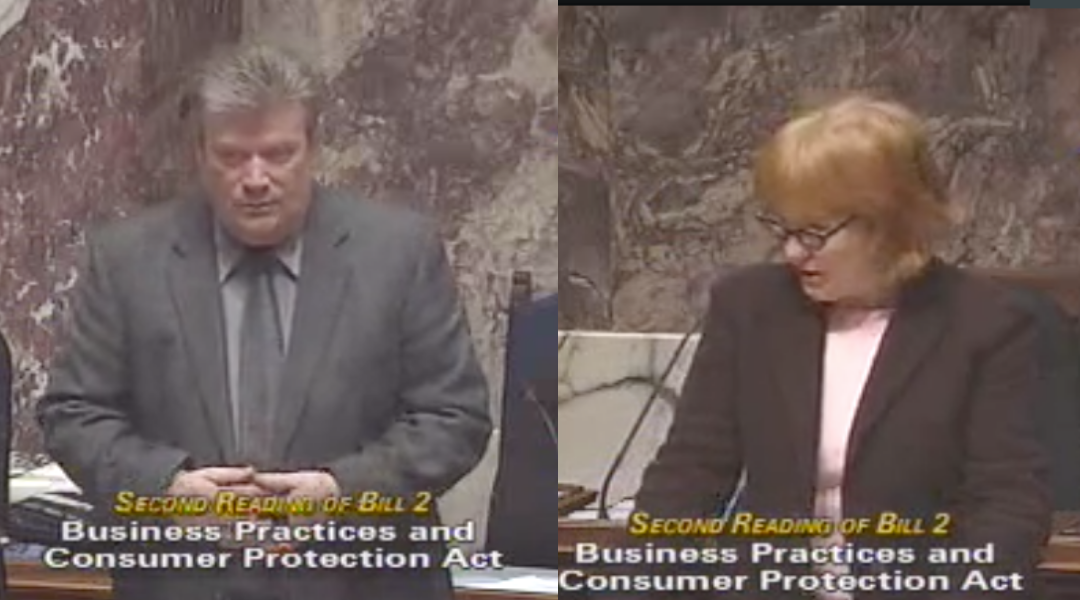

The Consumer Protection Authority’s enabling legislation was tabled in March 2004, before the third anniversary of Campbell’s mandate.

Then-Solicitor General Rich Coleman promised the new agency would have improved inspection and enforcement powers and would seize assets from lawbreaking businesses. The new authority would be governed by a board of directors as a non-profit corporation under an administrative agreement with government.

In March 2004, then-solicitor general Rich Coleman (left) faced questions from NDP leader Joy MacPhail about spinning-off consumer protection from the government. (Hansard B.C.)

“The creation of a new authority will ensure better consumer protection in the province by increasing industry and consumer involvement in consumer protection activities,” Coleman said in the Legislature.

Then-NDP opposition leader Joy MacPhail said the new authority would “allow this government to avoid its consumer protection responsibilities and off-load the costs associated with those activities on to the private sector.

“Where will the private sector get the money to pay for all of this? You guessed it — the consumer,” MacPhail said.

The maximum fine under CPBC’s legislation is $50,000 against a corporation and $5,000 for a person. Figures for 2018, the most-recent year available, show CPBC concluded 245 enforcement files and counted more than $414,000 in fines and restitution, up from $185,872 in 2017 and $100,078 in 2016.

A footnote in the report said the 154% increase in restitution for 2018 was due to refunds obtained from payday loan companies.

Support theBreaker.news for as low as $2 a month on Patreon. Find out how. Click here.