Bob Mackin

“Seasons’s greetings for COVID free, low stress holiday to everyone.”

That was how the lab boss at the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control signed-off an email on the morning of Dec. 21, when he circulated a colleague’s assessment of the United Kingdom variant of the coronavirus. It is one of several dozen email messages obtained by theBreaker.news under the freedom of information law.

BCCDC’s Natalie Prystajecky and Mel Krajden (BCCDC)

In a nutshell, Dr. Mel Krajden wrote, the U.K. variant “has not yet been identified in B.C. or in Canada.”

But that, along with the stress level, would rapidly change within a matter of days.

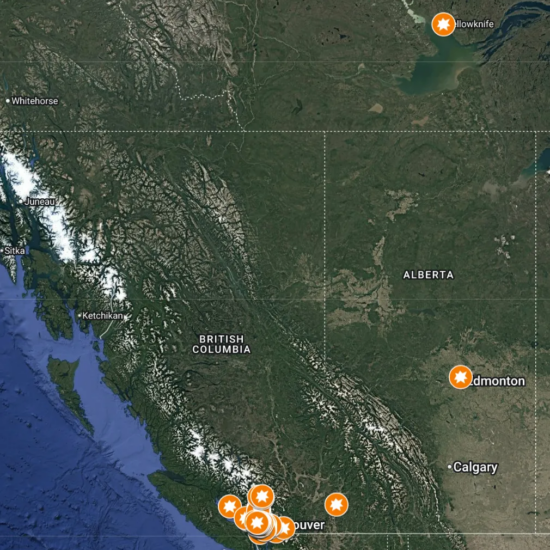

Hints of the U.K. variant had been already detected in B.C., specifically three mutations present in the U.K. variant’s 17 mutations. But nothing substantial out of the BCCDC’s 7,000 genome-sequenced COVID-19 samples, wrote environmental microbiology head Dr. Natalie Prystajecky.

“The one limitation is that we only sequence a proportion of B.C. cases (~20%) and could therefore miss it if it is a rare occurrence,” she wrote. “Cases with travel history, international travel or contact with a traveler will be prioritized for sequencing.”

Prystajecky’s assessment came on the heels of Dr. Theresa Tam’s conference call the previous day with the country’s top health and intergovernmental affairs officials. Canada’s top public health official Tam gave a brief tutorial on the variant, which had a “southern England/London locus” and was more transmissible, but not necessarily deadlier. Canada’s PCR testing would likely not be impacted, “though we are not sure whether other tests may be impacted,” she said.

A Public Health Agency of Canada document said 1,108 individuals in the U.K. had been confirmed with the variant by Dec. 13. Cases had been traced back to September, with a rapid November increase.

Little did they know, but someone had already brought the U.K. variant back to B.C. and it would change the course of the pandemic for the worse.

But did they move fast enough to tell the public?

Christmas Day email flurry

“Urgent — heads up — presumptive U.K. strain test result in Alberta,” wrote Michael Spowart, the PHAC director for B.C. and Alberta, to Tam late in the afternoon on Dec. 25.

Email obtained by theBreaker.news via freedom of information

“All we know right now is person came into YVR (connecting to Edmonton) from London Heathrow,” Spowart wrote in an email that he also sent to B.C. Provincial Health Officer Dr. Bonnie Henry.

At 8:21 p.m., Dr. David Patrick, BCCDC’s top research epidemiologist, reported he had been on a call with Alberta’s Dr. Deena Hinshaw, Tam’s deputy Dr. Howard Njoo and others. He learned that the passenger, who flew from London’s Heathrow Airport to Vancouver and then on to Edmonton, was asymptomatic in flight but developed symptoms, tested positive and had gone into isolation.

Another passenger had tested positive between rows 4 and 8. Limited sequencing found two mutations compatible with the U.K. variant. Complete sequencing would probably not be available before Dec. 27.

“We do not know this is U.K. variant for certain, messaging to contacts for now should be that we are being careful around the case originating from U.K.” Patrick wrote.

Henry replied at 8:45 p.m. “Delaying as much as we can is a good aim. Let me know if there are concerns about being able to trace people.

Air Canada 787-9 Dreamliner (Air Canada)

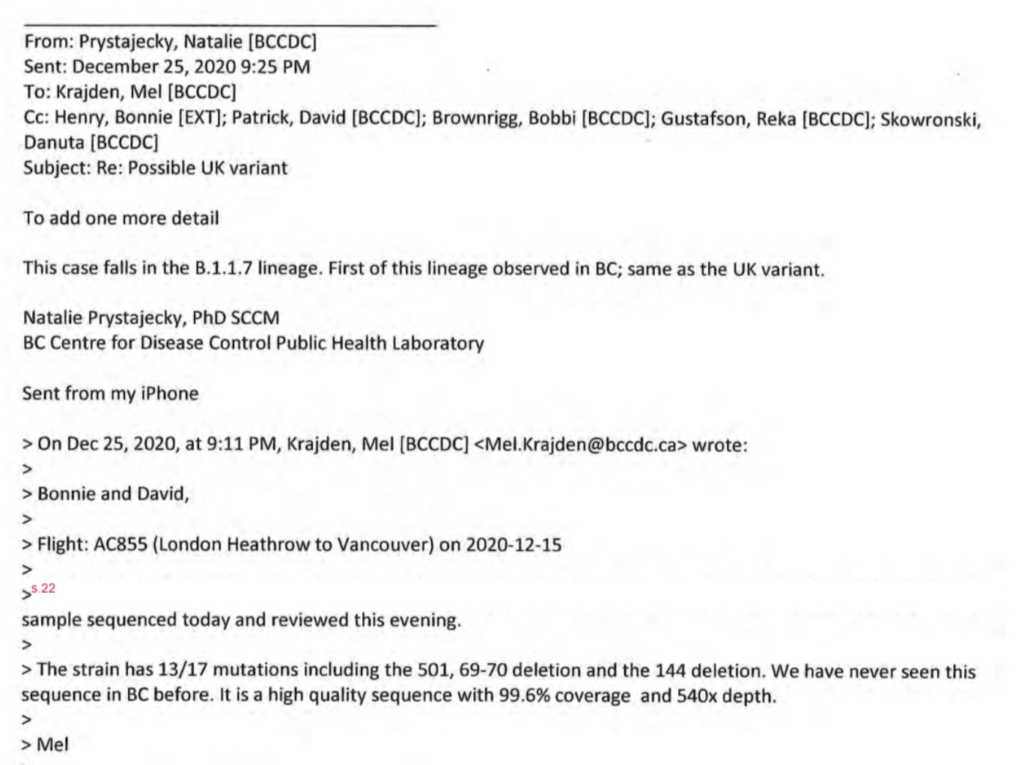

Krajden confirmed less than half an hour later, that the sample had been sequenced and reviewed on Christmas Day. It had 13 of the 17 mutations.

“We have never seen this sequence in B.C. before,” he wrote.

“To add one more detail,” interjected Prystajecky, “This case falls in the B.1.1.7 lineage. First of this lineage observed in B.C.; same as the U.K. variant.”

No Boxing Day rush

On Boxing Day, Ontario reported its first cases of the U.K. variant: a couple from Durham with no known travel history. But B.C. took a slow, methodical approach.

Just before noon on Dec. 26, Henry told the three BCCDC lab officials and her counterparts at Fraser Health and Island Health that a statement “about the B.C. case(s)” was being planned for the next day. “Details of the quarantine and when [symptoms] developed, contacts, etc. will be needed. I would appreciate if you can send me a synopsis when you get all that.”

Dr. Bonnie Henry on March 25 (BC Gov)

The next morning, Air Canada confirmed to Alberta officials that an ill passenger had exposed rows 12 to 16 on flight AC214, the Calgary-Vancouver route, on Dec. 19.

As B.C. officials prepared to release their statement, an Island Health official anticipated media questions. “The individual had to get from Vancouver to Vancouver Island — either by car, flight or ferry,” Island Health communications vice-president Jamie Braman wrote to the Ministry of Health’s Kirsten Youngs. “The media will most likely ask the question and we will need an answer to that question.”

Those details were omitted, as officials chose to err on the side of privacy in the 1:21 p.m. statement on the first U.K. variant case in B.C.

“The individual, who resides in the Island Health region, returned to B.C. from the U.K. on flight AC855 on Dec. 15, 2020, developed symptoms while in quarantine and was immediately tested. Testing confirmed the positive diagnosis on Dec. 19, 2020; a small number of close contacts have been isolated and public health is following up with them daily.”

Several media outlets had questions. More than three hours after the statement, Youngs told Henry that she was “able to politely/firmly decline some requests today but there five are outstanding [from CBC, Times-Colonist, CHEK TV, Globe and Mail and CHLY radio).”

BCCDC’s Dr. David Patrick (BCCDC)

Youngs recommended to decline all requests, but provide each a brief statement.

By the start of February, B.C. had officially recorded more than a dozen cases of the U.K. variant. But that would rapidly change.

In mid-April, with case counts exceeding 1,000 daily, Henry admitted the U.K. and Brazil variants accounted for 60% of new cases in B.C. Half of them the U.K. variant, dominant in Surrey, and 49% of them the P1, from Brazil, which dominated the Whistler resort outbreaks.

The spread of variants in B.C., which forced closure of Whistler Blackcomb and put the Vancouver Canucks’ season on hold for three weeks, attracted international media attention. Henry stopped daily reporting and said she assumed all new cases were one of the variants.

Krajden explained on GenomeBC’s May 4 web conference that B.C.’s variant detection was limited by genome sequencing and data analysis, so it changed strategies.

“Our sequencing capacity is pretty high, it’s about 1,900 a week, we’ve done some calculations to sample in an unbiased way from all regions of the province,” Krajden said. “With that sampling strategy we believe we will be able to detect as little as 1 in 200 or 1 in 500 of some variants that might occur.”

Support theBreaker.news for as low as $2 a month on Patreon. Find out how. Click here.