Bob Mackin

The former Commonwealth Games executive who heads Vancouver’s tourism industry association told theBreaker that nobody has asked him for advice on helping Victoria get the 2022 Games.

Ty Speer (Tourism Vancouver)

“I don’t have any particular kind of understanding on how Victoria intends to bid. I’ve not seen any sort of plans on how they want to stage the event,” said Ty Speer, the Tourism Vancouver CEO who was lured away from his job as deputy CEO of the Glasgow 2014 organizing committee. “I’m lacking quite a lot of information and, to be quite frank, nobody has contacted me and said ‘hey, how should we do this?’”

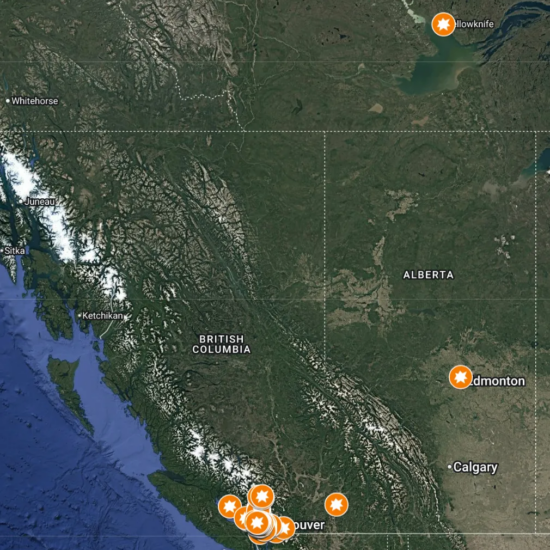

With five years to go, the Commonwealth Games Federation is searching for a host to replace Durban. The South African city won the bid by default in 2015 when Edmonton withdrew, but lost the rights in March due to disorganization.

Community newspaper publisher David Black announced he was heading Victoria’s bid on June 7. He gave few details about the budget, except for a low-ball, $100 million estimate to build an athletes village at the University of Victoria.

A Victoria 2022 Games would require hundreds of millions of dollars from both the federal and B.C. governments. The BC Liberals’ Vancouver Island platform for the May 9 provincial election contained a promise to back a bid, but the party held its lone seat on Vancouver Island, lost its province-wide majority and may be replaced by an alliance of the NDP and B.C. Greens. Green Party leader Andrew Weaver, whose party holds the balance of power, supports a Games bid in principle.

Speer said the timelines are tight, but Victoria 2022 would be possible if organizers can rely on reusing venues from 1994 when Victoria hosted the Commonwealth Games. Normally, mega-events are organized in seven-year, award-to-event cycles, owing to necessary infrastructure projects — such as competition and training venues, hotels, transit lines, and airport expansion.

Victoria 1994 logo

“It can be done in five years, but it would be, fundamentally, a function of how many construction projects,” Speer said.

Speer noted the Commonwealth Games have grown substantially since Victoria 1994, when 63 nations sent 2,557 athletes to compete in 10 sports. Glasgow 2014 featured 4,947 athletes from 71 national teams in 18 sports. By comparison, the Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympics had seven sports for 2,566 athletes from 82 nations.

“It’s grown in scale, it’s grown in complexity, obviously in terms of cost. The stature of the event has grown, so has the quality and sophistication,” Speer said. “The security climate, what we all have to contemplate now, does put costs on events. That is not a good thing, but it is a reality.”

Glasgow 2014 cost nearly $1 billion. Australia is budgeting $2 billion for the 2018 Games in the Gold Coast.

The size of the 21st century Commonwealth Games would mean Vancouver International Airport, BC Ferries and Lower Mainland hotels would inevitably play a role in Victoria planning. Would there be opportunities for Lower Mainland venues to host events, such as B.C. Place Stadium for opening and closing ceremonies and rugby sevens? One suburb already looked at making a bid, but found the prospect too ambitious.

“We looked at it, given the information we had and determined it wasn’t the right fit for us at the time,” said Jennifer Scott, Tourism Burnaby’s senior manager of sport tourism.

Burnaby is planning to replace its aging C.G. Brown Memorial Pool at the Burnaby Lake Sports Complex. It is near the privately-built Fortius Sport Centre, a state-of-the-art high performance training and sport medicine facility with on-site athlete accommodation.

Burnaby Mayor Derek Corrigan told theBreaker that it was “a little bit over our heads,” at a time when mega-events are riskier than ever.

Burnaby Mayor Derek Corrigan

“It was a lot of organization and commitment to take on, not something at this stage that I was prepared to take on,” Corrigan said. “That didn’t mean I was going to close the door to discussions with other cities.”

Referendum demanded

The leader of the opposition to the Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympics is now a Victoria resident. Chris Shaw said any decision to bid must be made by the public, not politicians under the influence of lobbyists and developers.

“They claim they can’t release their budget because of fears that the competitors will see it, but that’s patent nonsense,” Shaw told theBreaker. “They really don’t want the public to see it, because the public who might be able to do math can actually go in and look at the proposed outcomes and the costs to taxpayers and probably see that it doesn’t make sense financially.”

Shaw, author of Five Ring Circus: Myths and Realities of the Olympic Games, said he worries that the city could submit a winning bid without considering social, environmental and security impacts.

“It’s time to start a No Games Victoria 2022, because a lot of the stuff we saw back in the bid for the 2010 Olympics seems to be coming true in Victoria,” Shaw said. “It seems to be a developer-driven bid, and it’s remarkably short on details, on budget, a business plan and what they actually want to accomplish.

“The taxpayers are being asked to take on an enormous potential burden, for uncertain benefits, with almost complete secrecy surrounding the whole enterprise.”

British Columbians still don’t know the real facts or stats about Vancouver 2010. Organizers claimed they balanced a $1.9 billion budget, but that was $600 million more than contemplated in the 2003 bid. B.C.’s auditor general did not conduct a final report on Games spending. It is believed the total cost of operations, construction, transportation and security was around $7 billion. The $1 billion athletes village at False Creek went into receivership after the Games.

Vancouver 2010 organizing committee board minutes and financial books are held by the City of Vancouver Archives, but those files are sealed from public view until 2025.

Shaw said Victoria residents should be asking Mayor Lisa Helps and city council to hold “a binding referendum, on a clear question, with equal [campaign] funding for both sides, (and) a series of debates.”

Vancouver’s 2010 bid proceeded after citizens voted yes in a non-binding plebiscite after a campaign in which there were no fundraising or spending limits or disclosure requirements.

Games critic Chris Shaw (Mackin)

Birmingham and Liverpool are jockeying for the U.K. government’s nod to bid for the 2022 Commonwealth Games. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, the 1998 host, is also considering a bid.

Toronto hosted more than 6,000 athletes for the $2.5 billion Pan American Games in 2015 and pondered a bid for the 2024 Summer Olympics. In late May, city staff recommend against a 2022 Commonwealth Games bid because of the tight timelines, the lack of confirmed federal and provincial support and the lack of public consultation.

The International Olympic Committee is reeling from the aftermath of the corruption-tainted Rio 2016 Olympics and fewer cities want to host mega-events, because of skyrocketing costs. Beijing beat Almaty, Kakzahkstan for the 2022 Winter Olympics. Only Paris and Los Angeles are bidding for the 2024 summer Games. One of the cities will be awarded the 2028 Games.