Bob Mackin

The Winter Olympics may be closer to returning to 2010 host city Vancouver than you think.

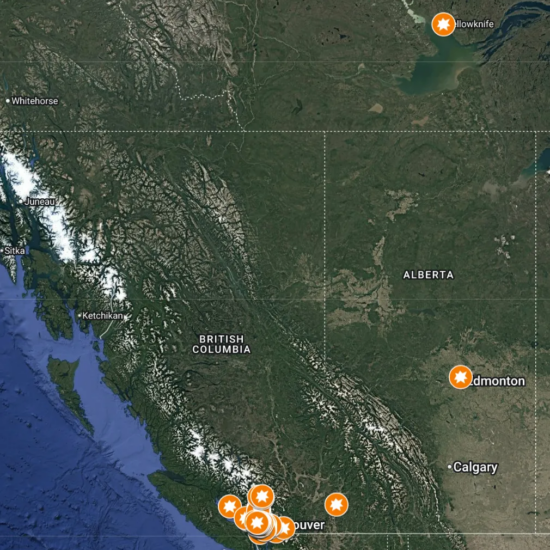

Vancouver city council will ponder a staff report on March 31 that recommends exploring a regional bid for the 2030 Winter Games.

The Olympic ski jumps in the Callaghan Valley, where the Games began Feb. 12, 2010, were closed 10 years later. (Mackin)

The politicians will not be hearing from the public on what could be the first step down a $5.2 billion road.

That is how much 1988 host Calgary estimated it would cost to hold the 2026 Winter Olympics. The bid relied on renovating 1988 venues, but voters eventually rejected it in 2018. Not before politicians spent $7 million on the process.

In 2019, the International Olympic Committee realized that fewer cities are ready, willing and able to host the Summer or Winter Games anymore. Especially after evidence arose about corruption in the winning Rio 2016 and Tokyo 2020 bids. So it adopted a new process to negotiate, or “dialogue” as the IOC likes to call it. The dialogue “can begin at anytime and will be led by the Canadian Olympic Committee.”

The Olympic cauldron in 2010 (Mackin)

“This new process means that any interested party can enter into a non-committal continuous dialogue with the IOC,” the staff report said. “There is no submission and no presentation by interested parties during the continuous dialogue. The initial dialogue does not have to target a specific year, thus the strict timelines and deadlines of the past have been eliminated. The goal of this new approach is to unlock greater value for future hosts as well as reducing costs across the board.”

This new process is how Brisbane, Australia suddenly became the frontrunner to host the 2032 Summer Games when it was declared the preferred bidder on Feb. 24. The IOC knows it is a buyer’s market and could very well anoint the 2018 Commonwealth Games host as the 2032 “rings-holder” much sooner than the 2025 deadline.

The deadline to pick a host for the 2030 Winter Games is 2023, which is two years before the 2025 opening of the Vancouver 2010 organizing committee’s agendas, minutes and financial records to public inspection at the Vancouver Archives.

The real costs of the 2010 Games remain a mystery, because the auditor general of B.C. never did a final report and VANOC was designed beyond the reach of the freedom of information laws. How could citizens make an informed choice in a plebiscite?

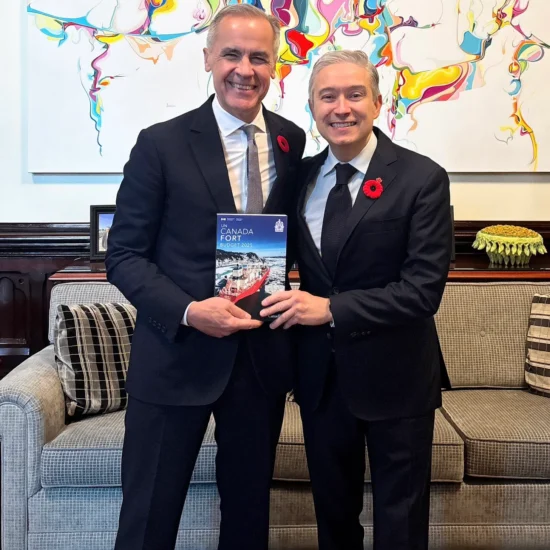

John Furlong (left) and RCMP Olympic security head Bud Mercer in 2010 (BudMercer.ca)

No surprise, the boosters for a 2030 bid are low-balling the costs on the basis of venue re-use. What they don’t say is the Richmond Olympic Oval and Hillcrest Community Centre would require significant retrofitting costs to bring long track speed skating and a curling arena back. Olympics also rely upon temporary structures — tenting, portables and fencing. Plus a $1 billion security bill.

The 2010 Games were leveraged to finally expand the Sea-to-Sky Highway, and build downtown to airport rapid transit and the downtown convention centre.

Mayor Kennedy Stewart has staked his re-election hopes on lobbying for SkyTrain to be extended from Arbutus to UBC and a huge influx of middle class and social housing. Vancouver would need to build another Olympic Village and local First Nations have the land.

To that end, the March 3 council-to-council meeting with the Squamish Nation included the 2030 bid and the desired subway on the agenda.

The North Vancouver-based Indian Act band already has plans to build towers around the south end of the Burrard Bridge. It is also a partner with the Musqueam Indian Band and Tsleil-Waututh Nation on the Jericho Lands in Point Grey, which is also a potential stop on the SkyTrain line.

The biggest headwind for a 2030 bid is the public purse. It is a lot lighter because of the pandemic. The federal debt could hit $1.1 trillion and B.C. is forecast at $88 billion. Higher taxes are inevitable, yet Vancouverites are also demanding an end to homelessness. The 2010 Games helped put more foreign millionaires in towers than Downtown Eastsiders in dry and clean beds.

Vancouver 2010 mascots Miga, Quatchi and Mukmuk (VANOC)

The head lobbyist for the 2030 bid is John Furlong, the VANOC CEO who fancies himself the chair of the next organizing committee, a la the late Jack Poole. Furlong’s legacy is tarnished, after parting ways with the Vancouver Whitecaps when the organization dithered about historic abuse and harassment of women’s team members in 2019.

The controversy over Furlong’s 2011 Patriot Hearts memoir is likely to reignite later this year. The Canadian Human Rights Tribunal will hear from six Lake Babine First Nation members who accuse the RCMP of racism for bungling the investigation of their allegations that Furlong abused them when they were children and he was a gym teacher. They also claim the RCMP protected Furlong because the Mounties were assigned the $900 million task of securing the 2010 Games.

Furlong has always denied the allegations, but the allegations have never been tested in a court of law. He filed defamation lawsuits, but then withdrew them, against the Georgia Straight and reporter Laura Robinson over their 2012 story headlined “John Furlong biography omits secret past in Burns Lake.”

Support theBreaker.news for as low as $2 a month on Patreon. Find out how. Click here.