Bob Mackin

In hindsight, the first sign that the Beijing 2008 Olympics weren’t going to translate to more basic freedoms for Chinese citizens was the pre-Games Internet clampdown.

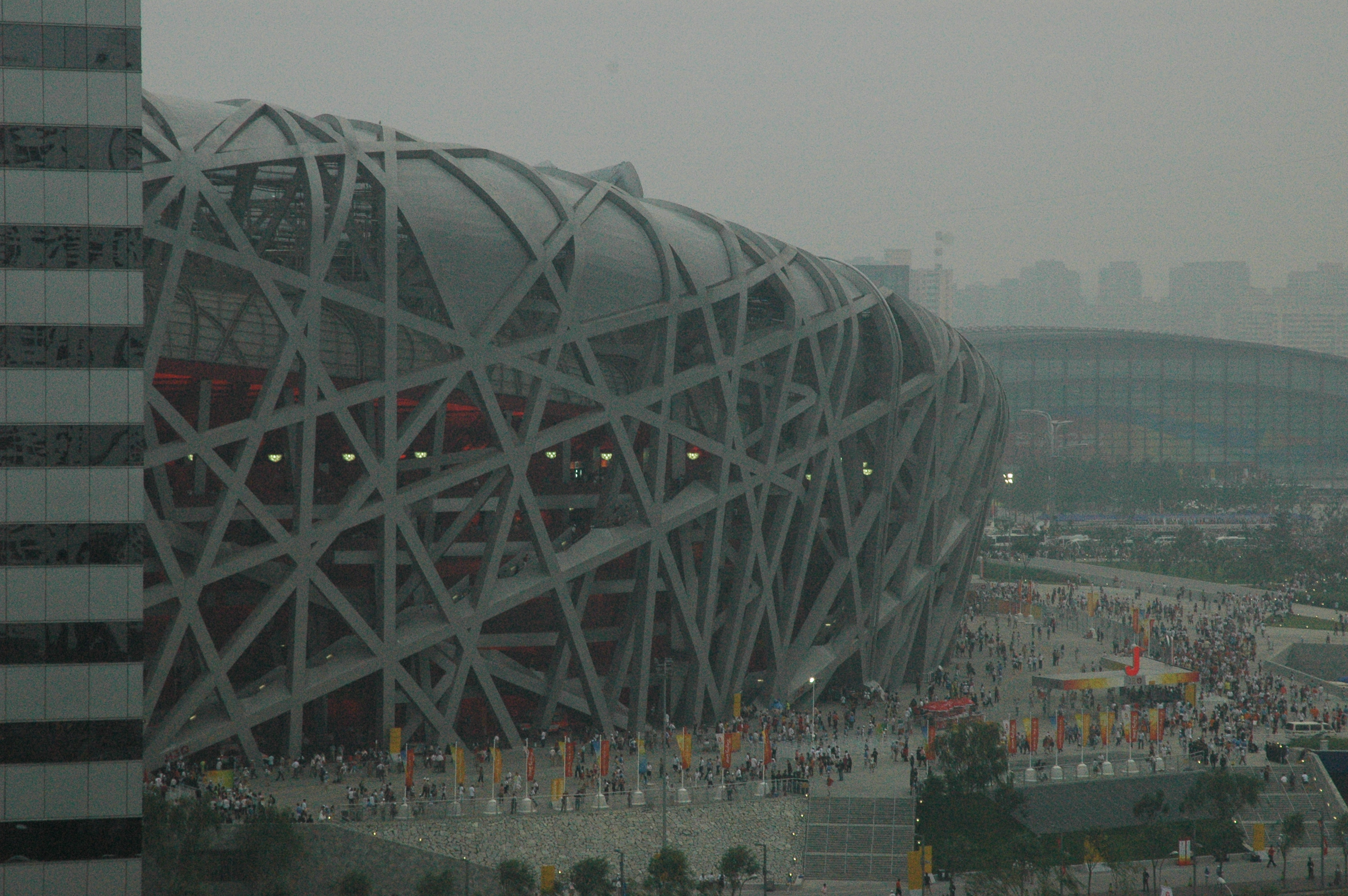

The Bird’s Nest on Aug. 8, 2008, as seen from the Huiyuan Media Village. (Bob Mackin)

The Chinese government had promised the International Olympic Committee that reporters from all nations would be able to surf the web, without any censorship, on the Olympic system. Reporters arrived at the main press centre and international broadcast centre to find various websites blocked, particularly those referring to Taiwan, Tibet and the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre.

The IOC’s press commission protested and the filter was adjusted. We got over the Great Firewall of China, but search engines continued to warn that sites on the T-topics contained viruses. After the world’s media went home, it returned to normal. Westerners and daring Chinese relied on VPNs to get them around or over the Great Firewall.

China was opening up, but on its terms and not the way the world really hoped. The 29th Olympic Games led to greater two-way trade, tourism and technology. And, eventually 2022: The next Winter Games are coming to China’s capital and its mountainous outskirts.

China is now a world leader in controlling news and online surveillance under President Xi Jinping, whose leader-for-life status was announced in time for the PyeongChang 2018 Winter Olympics closing ceremony. Prospects for basic freedoms by 2022 are dim and the censorship is likely to prevail again. Reporters Without Borders says more than 50 journalists and bloggers, that its knows of, are detained in China. Human rights activist and Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo was arrested four months after the Games opened and died in 2017. His widow, Liu Xia, was finally allowed to leave for Germany in July Meanwhile, the Beijing studio of dissident artist Ai Weiwei — who helped design the Bird’s Nest stadium — was demolished last weekend.

Chinese leader Hu Jintao is greets the Chinese team into the Olympics opening ceremony on Aug. 8, 2008 in Beijing. (Bob Mackin)

The Games opened Aug. 8, 2008, the most-unique and historic venue for a birthday I may ever have. My day began smoggy across the street at the Huiyuan Media Village, where the maid left a souvenir pin and panda toy on my pillow with a birthday greeting.

It ended in heat that I had not experienced before or since. By the end of the night, a pile of at least 10 empty plastic water bottles had formed under my seat in the Bird’s Nest. Manolo Romero, CEO of Beijing Olympic Broadcasting and managing director of Olympic Broadcasting Services, told me that thermometers at weather stations inside the National Stadium reached 50 degrees Celsius, a full 20 C hotter than outside the steel-framed structure. The host broadcaster was less worried about equipment overheating and more worried that a cameraman would expire. “That bowl is like a cooking vacuum,” Spaniard Romero remarked in an interview.

On the eve of the opening ceremony, I stopped for drinks with a friend from Vancouver at a rooftop bar in the old embassy district near Tiananmen Square. As we left to get to the British Columbia-government hosted reception, a waitress asked if we were part of the Goldman Sachs party that had booked the joint. What would we have learned about the global economic shock to come had we stayed and downed drinks with the Wall Streeters?

We arrived at the Beijing Planning Exhibition Hall to learn that Henry Kissinger, the former U.S. Secretary of State, had earlier made a short visit to the lobby, but not the B.C. pavilion. It was a career milestone for the honorary IOC member, who was instrumental under U.S. President Richard Nixon for opening relations with China and then-leader Mao Zedong in the early 1970s. I never did find out whether Kissinger visited Mao’s mausoleum across the street at Tiananmen Square.

Prime Minister Stephen Harper didn’t go. Predecessor Paul Martin skipped the opening of the 2004 Games in Athens; he was in Whitehorse, Yukon, instead. David Emerson, the Foreign minister known for crossing the floor from the Liberals to Conservatives, was at the B.C. government reception. Relations with China were improving, though the countries agreed to disagree on human rights. Emerson wasn’t about to say anything as newsworthy as U.S. President George Bush had already said.

The scene inside the Bird’s Nest in Beijing, at the opening ceremony of the 2008 Olympics (Mackin).

“We’re no shrinking violet on that issue, but we don’t choose to use the Olympics as the venue to make the point,” said Emerson, who led a delegation that included federal sport secretary Helena Guergis.

The People’s Liberation Army was stationed throughout the capital, never far from any of the venues. Later in the Games, the PLA mysteriously parked a tank next to the north entrance of the Main Press Centre. Games organizers said they didn’t know why it was there, which was hard to believe because the Games was organized by an arm of the government. Was it a show of force or a show of farce? The vehicle became a popular meeting point for reporters, near a designated pin-trading zone outside the gate.

I saw one reporter stand in front of it, attempting to recreate that iconic tank man moment from the Tiananmen Square Massacre of June 4, 1989.

I will never know if the uniformed local volunteers were perplexed, because they didn’t know what it meant. Or if they were too scared to admit they did, because they were under the constant gaze of surveillance cameras.

Support theBreaker.news for as low as $2 a month on Patreon. Find out how. Click here.