Bob Mackin

Political parties in British Columbia already benefit from indirect subsidies, thanks to a 1979-established tax credit system for donors. It costs the public treasury about $4 million a year.

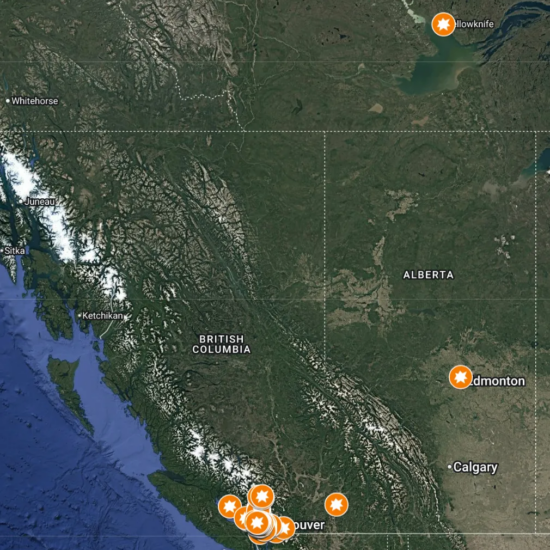

But if the Sept. 18-tabled Election Amendment Act is passed as-is by the Green-supported NDP government, political parties will get half their expenses reimbursed, a transition allowance until at least 2022 and a per-vote subsidy.

The measures that the NDP says will compensate for the ban on corporate and union donations, and the $1,200-per-year cap on individual giving, could cost taxpayers $27.5 million over the next four years.

Political parties are poised to reap a windfall of public money, so why not put them under the Freedom of Information law, so that the public can see how every dollar is spent and who is profiting?

“The parties have received public subsidies for a long time and should have been subject to FOI ever since they started receiving them,” Democracy Watch co-founder Duff Conacher told theBreaker. “Not only should they be covered by FOI, they should also be required to disclose detailed financial statements that are audited by the Auditor General or Elections BC.

“By detailed, I mean they wouldn’t just be able to put ‘Outreach’ as a line item, but would have to break that down into specific detailed activities and the amounts spent on each activity.”

Elections BC publishes the names of anyone who has donated $250 or more since 2005 and the NDP’s “ban big money” bill includes new requirements for reporting details of fundraising events seven days before and 60 days after. But Bill 3 does not mandate transparency. Annual reports to Elections BC contain hundreds of pages of names, dates and amounts of donations, but show nothing about who gets paid what. There could be massive corruption happening inside political parties and few would know.

During the 2015 deliberations of a joint BC Liberal/NDP committee to update B.C.’s Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (FIPPA), the Nova Scotia-based Centre for Law and Democracy said the law should apply generally to private bodies that receive public funding: “Although the FIPPA applies to most public authorities, its provisions do not apply to members or officers of the Legislative Assembly. FIPPA also does not cover private bodies that receive public funding, which should be subject to the law to the extent of that funding.”

The May 2016 report of the Special Committee to Review the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act stated that Commissioner Elizabeth Denham supported the Centre for Law and Democracy’s recommendation to extend FIPPA to “cover any entity that is performing a public function.”

Political parties in democracies should be bottom-up, not top-down, organizations that openly draft, debate and decide policy. Campaign strategies are a different matter and parties guard those with good reason. There are enough exceptions in the FOI law that would still protect sensitive information, such as intellectual property, from being disclosed to the curious.

Ultimately, the committee recommended the narrower path of extending FIPPA to “any board, committee, commissioner, panel, agency or corporation that is created or owned by a public body and all the members or officers of which are appointed or chosen by or under the authority of that public body.”

During the spring election, the NDP promised improvements to the FOI law, but they weren’t in the throne speech and won’t be introduced before 2018.

While Canadian political parties are not subject to freedom of information, political parties in Mexico are. Canada’s other NAFTA partner has long struggled with corruption and has enacted a variety of reforms to level the playing field.

Still, Canada’s federal Access to Information law offers a potential model in the form of a Crown corporation whose intellectual property is protected.

In 2007, the federal Conservative government put CBC/Radio-Canada under the federal public records law, but included a specific exemption for the national public broadcaster for “any information… that relates to [CBC] journalistic, creative or programming activities, other than information that relates to its general administration.”

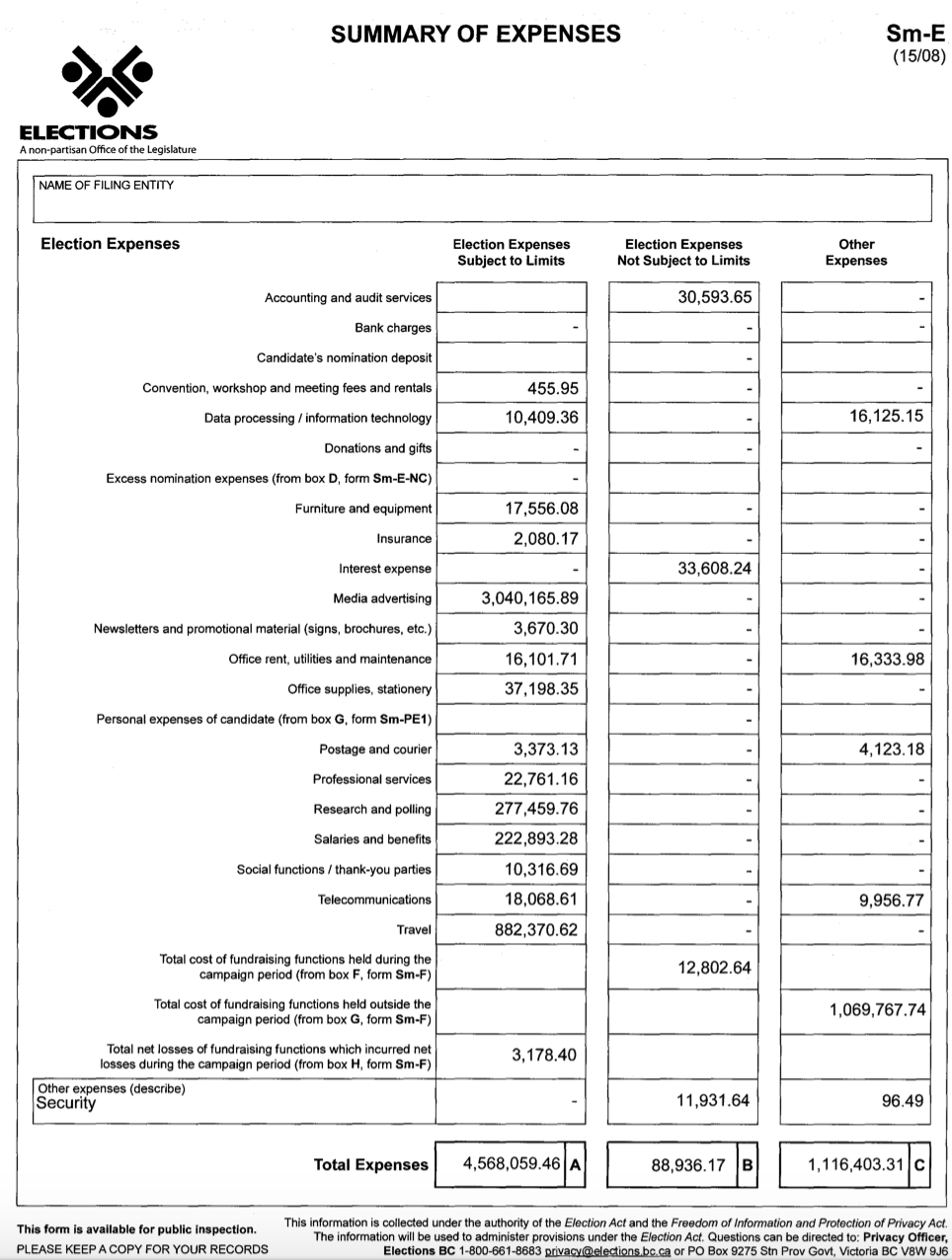

BC Liberals said how much they spent, but not who got paid (Elections BC)

As such, the CBC website includes a trove of documents released to ATIP requesters in categories such as administration, audits, contracts, expenses, external legal fees, policies and retreats. But nothing that would compromise the news-gathering at the Mother Corp.

If the nation’s biggest media outlet, which competes for advertising revenue with private companies, can operate under a sunshine law that protects its intellectual property, then why not a political party in B.C., like the NDP or BC Liberals, that stands to gain millions in subsidies under a new campaign financing regimen?

But why stop there?

Caucus communication offices at the Legislature are exempt from B.C.’s FOI law. Those offices tend to be filled with political appointees who use taxpayers’ money to craft messages to promote their party (and denigrate others) between elections. The results of their work are exhibited on social media, for instance.

In 2013, the leaked BC Liberal multicultural outreach strategy playbook, also known as Quick Wins, showed how the ruling party blurred the lines between governing and campaigning. BC Liberal aide Brian Bonney was charged with breach of trust.

Before this year’s election, BC Liberal leadership hopeful Andrew Wilkinson spent $59,000 of his $120,000 constituency office budget on radio advertising that extended far beyond his posh Vancouver-Quilchena riding. We know that not because of FOI — MLAs’ riding offices are exempt — but because the Legislative management committee decided in 2015 to release quarterly expense reports.

Wilkinson was also the minister in charge of Government Communications and Public Engagement, which spent $20.5 million of taxpayers’ funds on pre-election advertising. The 2015-launched Our Opportunity Is Here ad campaign sparked a B.C. Supreme Court lawsuit aimed at forcing the BC Liberal Party to repay the treasury. The plaintiffs, who seek class action status, claim the ads were strategically designed to benefit the party’s re-election campaign, without any cost to the party.