Bob Mackin

B.C.’s NDP government finally tabled its promised campaign finance reform bill Sept. 18, two months after it was sworn-in.

B.C. NDP’s last big money fundraiser?

During the spring election, Premier John Horgan vowed it would be the “first order of business.” In August, he said it would be the first bill after the throne speech. It turned out to be Bill 3, after the throne speech and the budget. But it won’t be law by Friday, when Horgan hosts a $525-per-person fundraiser at the Hotel Vancouver to pay-off the NDP campaign debt. A source close to the party told theBreaker that it was as high as $1.8 million in early August.

The Election Amendment Act bans corporate and union donations, and restricts donations to $1,200 a year by individual B.C. residents who are Canadian citizens or permanent residents. Parties will be eligible to a partial subsidy; taxpayers were already indirectly subsidizing parties through tax credits that cost the public treasury about $4 million a year.

But Democracy Watch’s co-founder says the $1,200 cap remains an excessive amount and businesses and unions will find ways around it. The NDP bill won’t ban big money, said Duff Conacher. It will only hide it.

“The $1,200 donation limit is much higher than an average voter can afford in B.C., and therefore it’s undemocratic, it will allow wealthy people to continue using money as an undemocratifc and unethical means of influence, and it will also facilitate funneling, as you’ve seen in Quebec, federally and in Toronto,” Conacher said.

Conacher said B.C. should have followed Quebec, which set $100 per individual in 2013 as the annual limit after businesses exploited loopholes in that province’s corporate and union donation ban. Provincial auditors found workers at 532 law and accounting firms, construction companies and engineering-consulting businesses donated $12.8 million to major parties between 2006 and 2011. Nearly 83% of the donations were $1,000 or more.

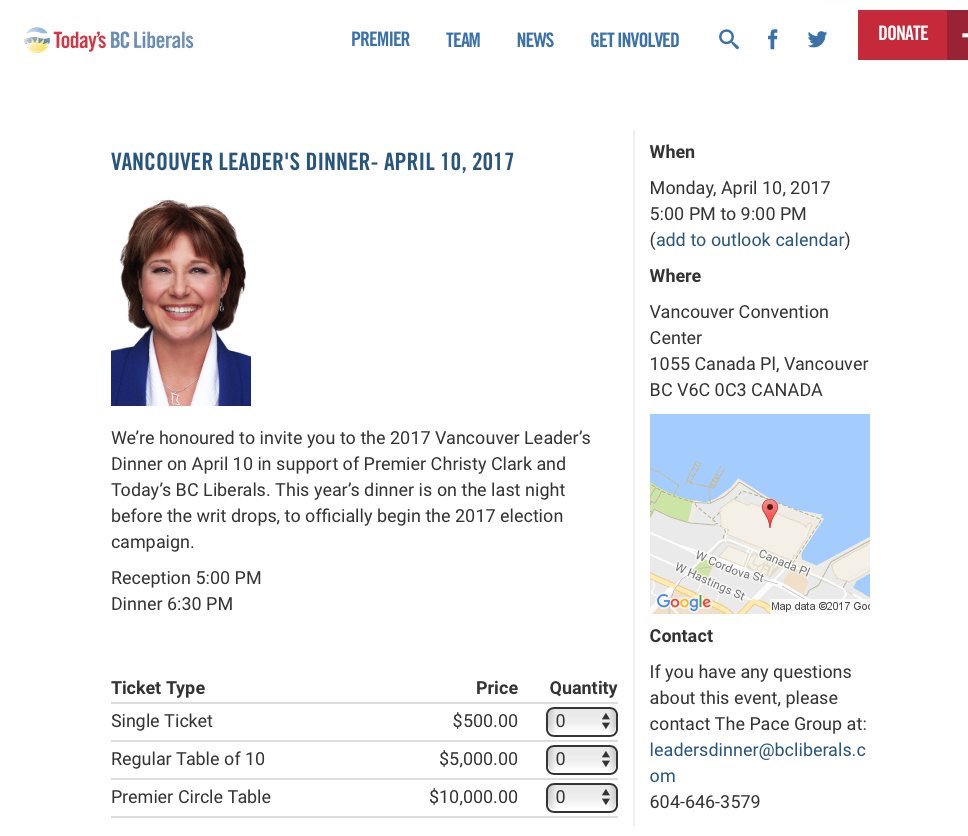

Clark’s last pre-election fundraiser.

“Even if it’s illegal, which it is already, to funnel a donation through someone else in B.C., you won’t stop it because you go to the business or the union and say ‘did you give this money to your executive, on the condition they pass it on to a party?’ and they’ll say ‘no’,” Conacher said. “It’s so easy to give a Christmas bonus and have that be actually on condition to passing it on to a party. How do you prove that?”

The Charbonneau Commission on corruption in Quebec’s construction industry heard testimony in 2013 from SNC-Lavalin senior vice-president Yves Cadotte, who admitted “we organized ourselves to have our employees contribute to political parties.”

That amounted to $1.05 million to provincial parties from 1998 to 2010 and $118,000 federally from 2004 to 2011. Elections Canada found SNC-Lavalin reimbursed employee donations to the Liberals and Conservatives “in the form of false refunds for personal expenses or payment of fictitious bonuses or other benefits.”

Overall, positive

The NDP reported that it raised $9.125 million for the 2017 election, including $3.07 million from unions and $1.4 million from corporations. Its largest donor was the United Steelworkers at a whopping $757,614.87.

The Liberals said they spent $13.7 million, of which $4.2 million was raised from corporations. The party grossed $2.9 million at cash for access fundraising events, but deposited $1.8 million after costs. The Green Party won the balance of power in the election and spent only $905,000. While it claimed a self-imposed ban on corporate and union donations, corporate money still found its way into party coffers. For instance, Elizabeth Beedie, wife and mother of real estate tycoons Keith and Ryan Beedie, donated $20,000 to Andrew Weaver’s party.

Political fundraising in B.C. reached a peak — or a low, depending on your perspective — in February 2016. The BC Liberals reported banking $1.65 million in donations on Feb. 26, 2016. Some $1.1 million came from eight, mostly real estate industry donors involved in a private fundraising dinner on Feb. 23, 2016 that theBreaker revealed. The fundraising hurricane included $400,000 to the party from real estate tycoons Peter and Bruno Wall, three days before they sold Chinatown land to B.C. Housing for $6.7 million. The housing minister at the time? BC Liberal campaign co-chair and deputy premier Rich Coleman.

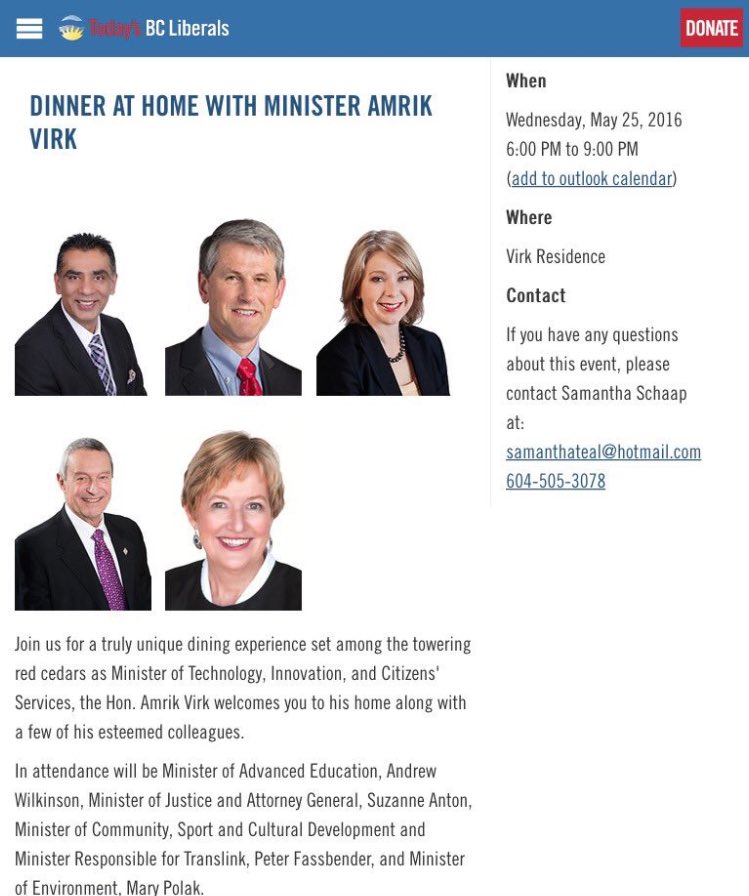

Five cabinet ministers for $1,000 in 2016.

IntegrityBC’s Dermod Travis, author of May I Take Your Order Please?, the definitive e-book on campaign financing in B.C., said his overall impression of the bill was “positive.”

He said the government backed-off on making the ban retroactive; donations made since the election are allowed to pay-off a party’s campaign debt, not pay for the next election campaign. It also doesn’t apply to the BC Liberal leadership contest that will climax in February.

Travis said he was happy to see a 25% cut in the spending cap, intrigued with the reimbursement up to 50% on eligible expenses, but “baffled why any political party needs a transitionary allowance.”

Until 2022, at least, parties will get a per-voter subsidy to help wean them off corporate and union fundraisers. Subsidies aren’t entirely new. Donations of $1,500 are eligible for the maximum $500 income tax credit.

“Liberals and NDP, if they look at what parties have spent in other provinces on party operations, they don’t need a transitionary allowance — they need a new belt,” Travis said. While the BC Liberals spent $7.25 million in 2014, the Alberta Progressive Conservatives spent $3.5 million. (After winning the 2015 election, the Alberta NDP banned corporate and union donations.)

Fundraisers involving major party leaders, cabinet ministers and parliamentary secretaries must be reported to Elections BC at least a week in advance, but the name of the host and location won’t be published if at a private residence. No later than 60 days after a function, the attendees and amounts raised must be reported to Elections BC.

Like Conacher, Travis is concerned about party supporters using loopholes to subvert the corporate and union ban. A requirement that donors list the name of their employer would be a safeguard.

“Something that’s going to be very critical if you want to make sure companies are not using their employees to get around the corporate ban, and unions using their staff to do the same,” Travis said.

Before the election, the RCMP and a special prosecutor launched an investigation into illegal donations from lobbyists.

There is no new money on the table for Elections BC to undertake compliance and enforcement. Yet.

Attorney General David Eby’s office told theBreaker that if chief electoral officer Keith Archer needs more resources, he will have to ask the Standing Committee on Finance, where all legislative officers go with budget requests.