Doris Gómora

The first time that I was so close to Joaquin “El Chapo” (“Shorty”) Guzman Loera was in the high-security Federal Jail in Almoloya de Juarez, Mexico. I was part of a group of press reporters that got authorization to access inside the jail. We covered Raul Salinas de Gortari’s trial, and during a break, I crossed the hallway to the next room, where “Shorty” Guzman was.

The judge and Mexican government never authorized press reporters to watch the first trial of Guzmán. But in the United States that would be very different: it was an historic opportunity for press reporters to be in the gallery for Guzman’s trial, to know about his associates, about his illegal business, about bribes that he ordered to pay to politicians and government officers in several countries, and maybe know some anecdotes.

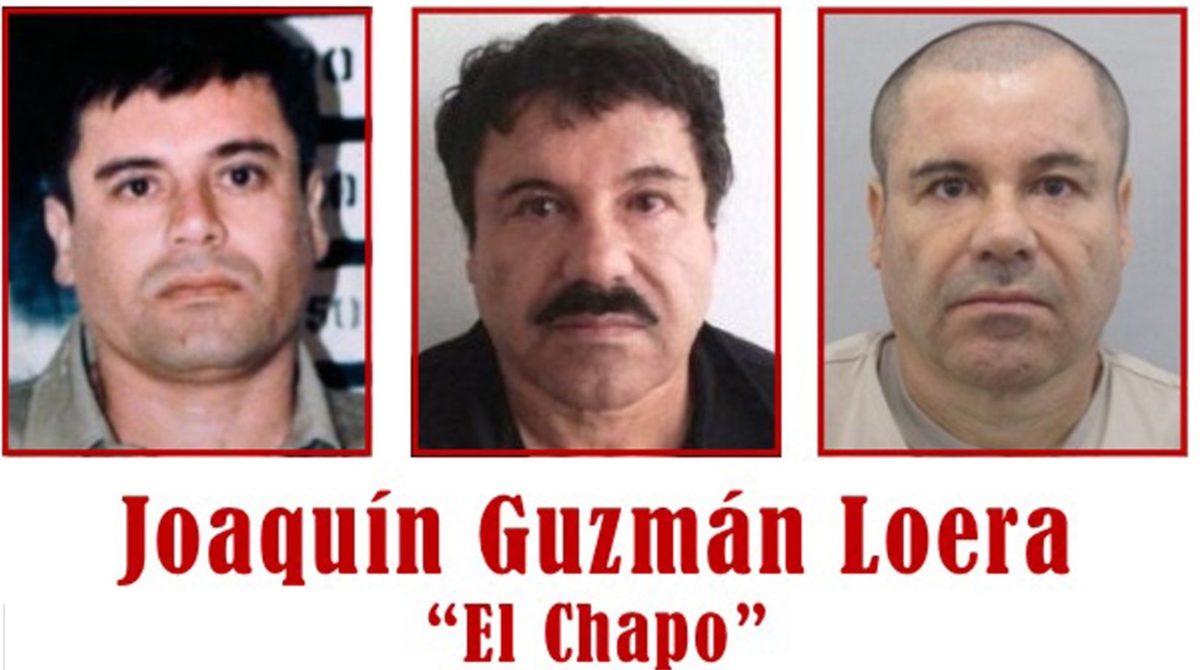

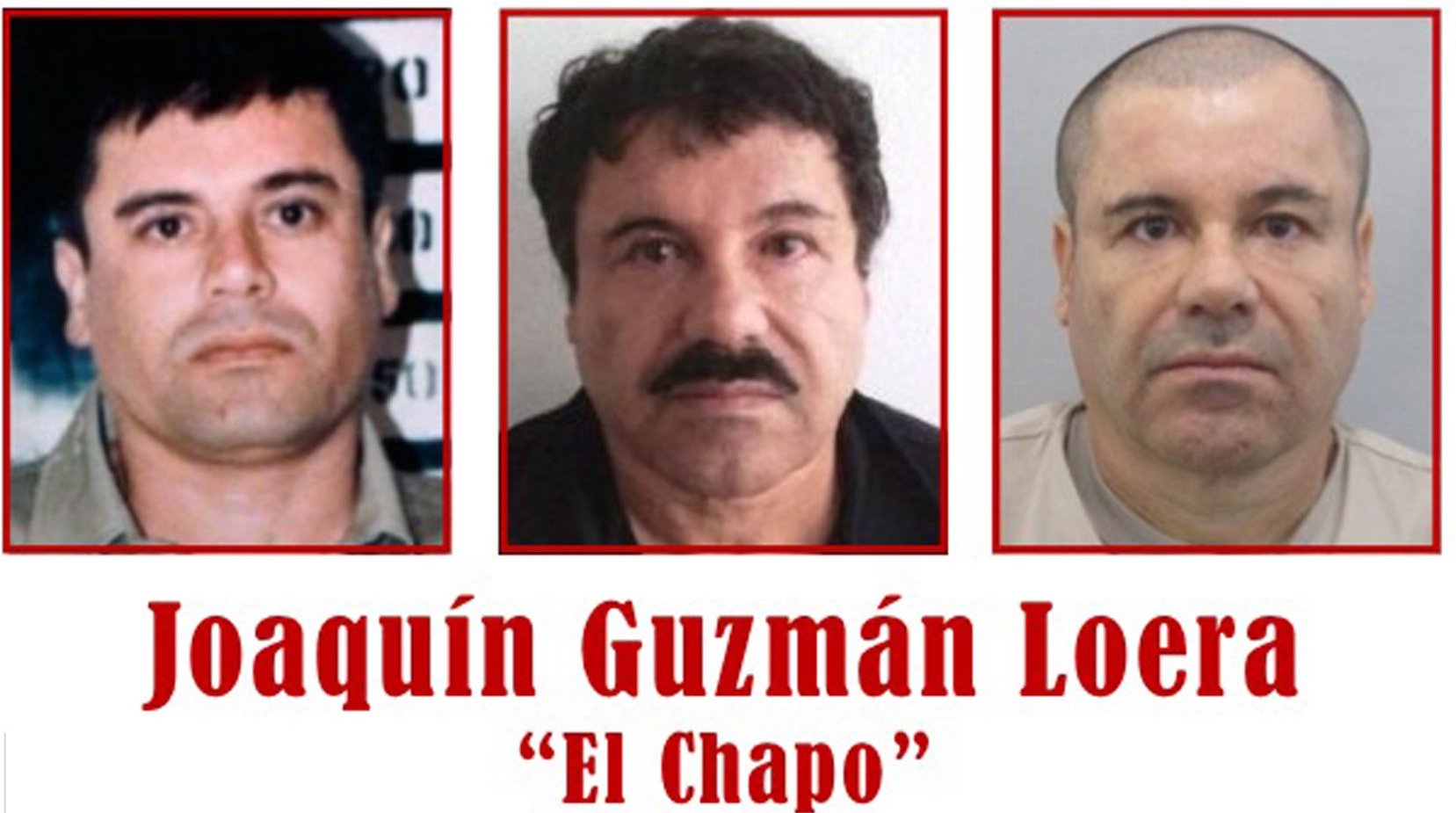

(DEA)

Many answers will come in the courtroom in New York, when Guzman’s blockbuster trial begins Nov. 13.

In Mexico, Guzman’s first trial was inside of the number 1, high-security federal jail, originally built without courtrooms.

But with Guzman and other kingpins in jail, and with a high risk to move them to a courthouse, the Mexican government adapted part of the jail and separated the gallery by glass from the prisoners.

I covered, for El Financiero newspaper, the trials of suspects in the murder of Luis Donaldo Colosio, the former presidential candidate, and Francisco Ruiz Massieu, the former general secretary of the PRI political party. They were killed in March and September of 1994, respectively.

Sometimes I covered news about Gulf Cartel members, and learned about the way of life for prisoners inside that federal jail, all of them high-ranking members of organized crime.

Reporters only accessed the inside of federal jail if the Ministry of Interior (aka Gobernacion) granted authorization. So, every day reporters arrived outside of the federal jail and wrote their names on a sheet, to show their interest in covering those trials.

We gave that list to the external security chief of the federal jail. With clearance, we used to walk a couple of miles to the main entrance with just a paper notebook and transparent plastic pen.

After strict security screening, sometimes with dogs, security officers took us to the courtroom.

From time to time, press reporters got authorization to watch the Othon Cortes trial or Raul Salinas trial, and very rarely, in the next room, the trials of drug trafficking kingpins.

One day in 1995, I took time to be in Guzman’s gallery.

I was in my mid-20s. I remember that older reporters told me about the man in the next room.

“It’s ‘Shorty’ Guzman, the drug dealer captured in Guatemala,” they said.

So, I remembered that in June of 1993, Guatemalan authorities captured Guzman with a woman, his girlfriend, and later put them in the custody of Mexican authorities.

On June 18, in an open yard of the high-security Almoloya federal jail, Mexican authorities presented Guzman to press reporters. It was a very rainy day.

Suddenly, photographers asked him to get out of his light brown jail uniform. He did it, and meanwhile, somebody asked him: ”What do you do for a living?”

With a very calm voice, he answered: “I’m a farmer.”

The Mexican government never granted authorization to press reporters to watch Guzmán’s court appearances. Not officially. One day in a break of the Raúl Salinas case, I watched Guzman’s court appearance. In the left corner of the section of prisoners, two men in federal prisoners uniforms were very close to each other, and around three feet apart. To the right it was Guzman.

A federal jail security guard close to me said: “those two guys were lieutenants of Guzman, and it’s probable they’re going to die because in the last 30 minutes they declared against him. And you, please, move out.”

I asked him to let me stay a little moment, and he agreed.

Then the judge ordered Guzman to answer to the accusations.

Guzman turned his head to the former lieutenants and just said: “Really?” The former drug traffickers were terrified and said: “No, no. We are wrong. We want to change our statement.”

Mexican fiscal attorneys could not believe how, with just a phrase, Guzman changed everything. Meanwhile, I just thought: Why are they so afraid? Guzman turned his head to us and then reporters were removed from the room.

Then, Macario Lozano, another reporter told me: “‘Shorty’ Guzman is terrible.”

Why? Because, Macario said, they were afraid of the way he looked at them.

I saw Guzman other times, and I learned about his life inside the jail.

And I remember something strange: after many years without maintenance, suddenly the rural road that crossed the land of the federal jail was rebuilt in a couple of months.

The plan was to connect a rural road with the highway. But on Nov. 22, 1995, when Mexican authorities transferred Guzman to the federal jail in Jalisco, work stopped. Ten years later, he used that highway to run away.

On Jan. 19, 2001, Joaquin Guzman Loera escaped from Jalisco federal jail. On Feb. 22, 2014, he was recaptured and transferred to the federal jail in Almoloya. On July 11, 2015, he escaped again.

On Jan. 8, 2016 Mexican authorities recaptured him and, on Jan. 19, 2017, they extradited him to the United States.

Joaquin Guzman Loera was public enemy number 1. Now he is in the United States and his trial will offer many answers.

That is why it is so important that press reporters will be inside of the courtroom, to know those answers.

- Doris Gómora is a Mexican freelance journalist.

Support theBreaker.news for as low as $2 a month on Patreon. Find out how. Click here.