Bob Mackin (Updated Jan. 8)

Say it ain’t so, Dubow.

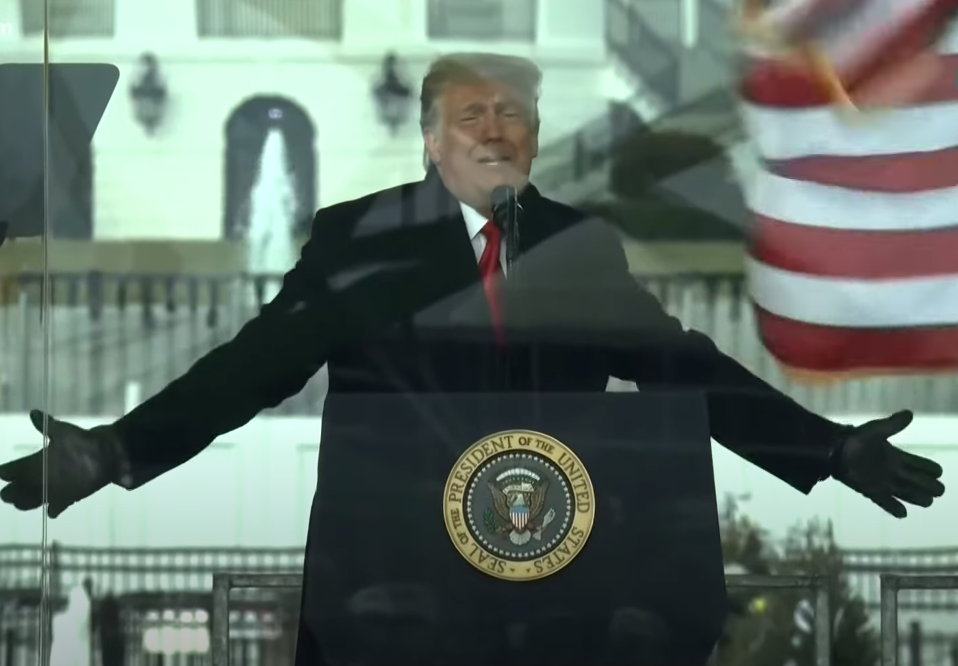

The Somalian refugee who became a Victoria city councillor in 2018, Sharmarke Dubow, is apologizing after he disobeyed public health orders and jetted to his homeland for a late-2020 vacation.

Sharmarke Dubow in 2019 in Ethiopia (Twitter)

Dubow unofficially leads all other Canadian politicians for longest distance traveled for a non-essential holiday during the second wave of the pandemic: Victoria to Mogadishu, the capital of Somalia, is almost 18,000 miles, round trip.

The Times-Colonist reported Dubow admitted it was a “poor choice” to fly to East Africa. He claimed to now be a in a 14-day quarantine at a Vancouver hotel after returning Jan. 3 to Canada. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warned against all travel to Somalia because of the very high risk of catching the deadly virus.

“I understand that many people made the difficult decision not to visit their families over the past number of months. I know now that I should have made the same decision,” wrote Dubow, whose given name means “see no evil.”

Dubow was seventh in voting for the eight city council seats in the 2018 election. He ran for election in Victoria, though he lived in neighbouring Esquimalt.

Dubow is on the board of the NDP-aligned Broadbent Institute, whose PressProgress arm has published hard-hitting stories critical of conservative politicians who flouted the rules. theBreaker.news has sought comment from the Broadbent Institute about Dubow’s leisure travel. Likewise, theBreaker.news has sought comment from BC Transit chair Susan Brice, because Dubow is on the public transit agency’s board.

PressProgress/Twitter

Dubow claimed the trip was his first to East Africa since fleeing civil war in Somalia in 1992. But he Tweeted in December 2019 about visiting Ethiopia, and said at the time it was his first visit there since 2001.

In addition to Dubow, Metchosin Coun. Kyara Kahakauwila traveled to Mexico for a friend’s wedding.

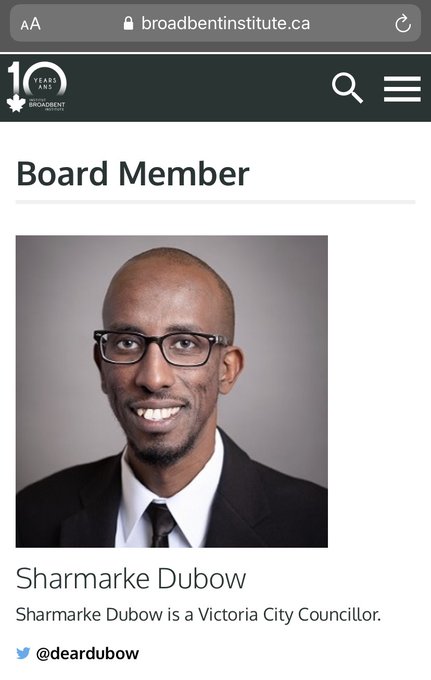

On Jan. 6, Victoria Mayor Lisa Helps called Dubow’s choice “both disappointing and irresponsible.”

“As community leaders, we should be held to a higher standard,” Helps told reporters at city hall. “We should be exemplary role models, following the public health advice that we’ve all received.”

North Saanich Coun. Heather Gartshore told the Times Colonist she had traveled to Seattle before the travel advisory, but gave no details.

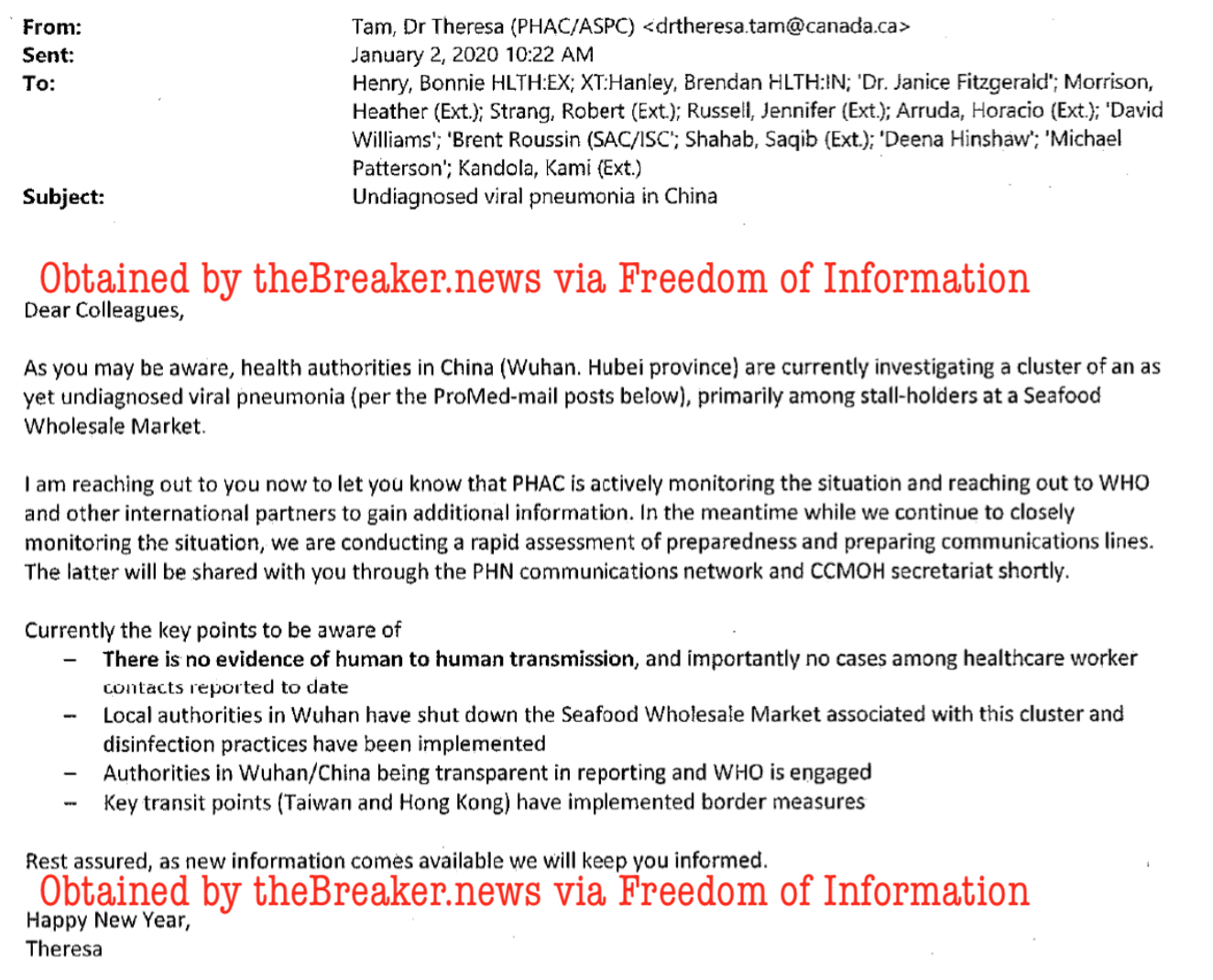

Meanwhile, Gil Kelley is the Lower Mainland’s leading contestant for a similar dubious distinction.

theBreaker.news was first to report Jan. 4 that the City of Vancouver general manager of planning had disobeyed orders to avoid non-essential travel.

Kelley left the city sometime after being spotted at a Nov. 22 coffee meeting with Coromandel developer and ex-city councillor Raymond Louie.

Unlike globetrotting, disgraced provincial cabinet ministers Rod Phillips of Ontario (St. Bart’s) and Tracy Allard of Alberta (Hawaii), Kelley stayed in the rainy Pacific Northwest.

Kelley, a former top planning official in San Francisco and Portland, did not respond to theBreaker.news.

City of Vancouver’s Gil Kelley (EGA Talks/YouTube)

City hall spokeswoman Gail Pickard initially refused to comment and referred theBreaker.news to the freedom of information department. Later, Pickard delivered a statement on behalf of Kelley saying that he left to attend to personal, family affairs at his Oregon property in late November. He is planning to return to Vancouver Jan. 8 and pledges to abide by quarantine orders upon his return.

theBreaker.news is still waiting for reaction from Mayor Kennedy Stewart’s office. Stewart’s chief of staff, Neil Monckton, said Stewart stayed home in Vancouver during the holidays.

West Vancouver Coun. Peter Lambur told the North Shore News he left after the last council meeting of 2020, on Dec. 16, to Big Sur, Calif. to see his six-month-old granddaughter for the first time. The trip included Los Angeles County, one of the virus hot spots in the U.S. He is back home in the middle of a 14-day quarantine.

“While I planned my travels with safety as my uppermost concern, I neglected to consider how, in my role as a local government elected official, my actions might be viewed by you, West Van residents, particularly given a worsening environment fraught with frustration as pandemic metrics continue to stubbornly resist improvement,” Lambur said in a prepared statement on Jan. 8. “In retrospect, I see this as a lapse of judgement and apologize to those who are upset and angered by my decision to travel when many of you put your own plans on hold. I am sincerely sorry.”

Meanwhile, West Vancouver’s mayor wants more clarity from the provincial health officer after realizing she may have skied into a grey area by visiting Whistler over the holidays.

There are no laws banning travel within the province during the pandemic state of emergency. On Nov. 7, Dr. Bonnie Henry did recommend B.C. residents avoid non-essential travel outside their region.

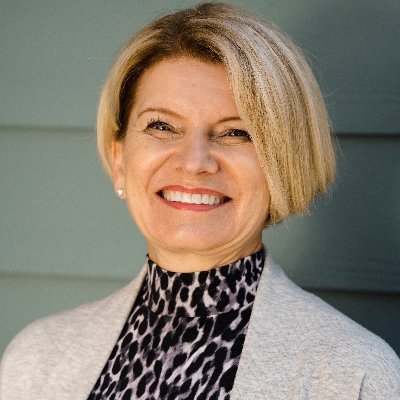

Mayor Mary-Ann Booth told theBreaker.news she went with her husband, two daughters and dog and cat to their Whistler cabin from Dec. 20-Jan. 2. She went skiing at Whistler Blackcomb on three of those days.

West Vancouver Mayor Mary-Ann Booth (Twitter)

West Vancouver and Whistler are both within the Vancouver Coastal Health region. Upon return, Booth said she found this line on the provincial health officer’s website under the headline Travel for mountain sports: “Ski and snowboard at your local mountains. For example, if you live in Vancouver, you should ski at Cypress, Grouse or Mt. Seymour.”

“It didn’t cross my mind that it was covered by a travel restriction, we do treat it like our second home, we didn’t have any visitors,” Booth said. “When I reviewed it, I just reviewed it yesterday, it is grey. For example, people that live in Burnaby, could they come to the North Shore? So Surrey, could they come to the North Shore, are those their local mountains. It is confusing.”

Judging from traffic jams on the Upper Levels Highway, and congested parking lots at Seymour, Grouse and Cypress in the days before and after Christmas, it looked like the North Shore mountains drew many visitors from places like Burnaby and Surrey.

Booth said she hasn’t otherwise traveled. She cancelled a Palm Springs trip right when the pandemic was declared back in March. While she said she supports Dr. Bonnie Henry’s orders Booth told theBreaker.news that she plans to bring up the need for more clarity at the next Metro Vancouver meeting and her next conference calls with provincial officials. Most recently, she discussed the vaccine rollout with new Municipal Affairs Minister Josie Osborne and Deputy Provincial Health Officer Dr. Brian Emerson.

“My motto in life is ‘making it easy for people to do the right thing, is being really clear on why you’re doing it’,” Booth said.

Booth appears to have an ally in a B.C. Supreme Court judge.

In a divorce case ruling on Dec. 22, Justice Nigel Kent decided the defendant, who entered a polyamorous relationship, was not in breach of public health orders when his girlfriend and her husband visited his home. (theBreaker.news is not referring to the parties by name to protect their children.)

Kent referred to the orders made since Nov. 7 by Dr. Bonnie Henry, which have been regularly amended, repealed and replaced.

“The messaging accompanying these orders, and indeed the language of the orders themselves, is fraught with inconsistency and ambiguity and it is not surprising that reasonable people can reasonably disagree about their interpretation and application in any given circumstance,” Kent ruled.

“Such confusion was graphically demonstrated this past weekend when the premier of British Columbia himself, relying on advice provided by his Minister of Health, announced his intention of spending Christmas Day at home with his wife, his son, and his daughter-in-law, and was obliged to change his plans when it was pointed out to him that such a gathering was actually a breach of one or more of the PHOs currently in force.”

What other mayors said

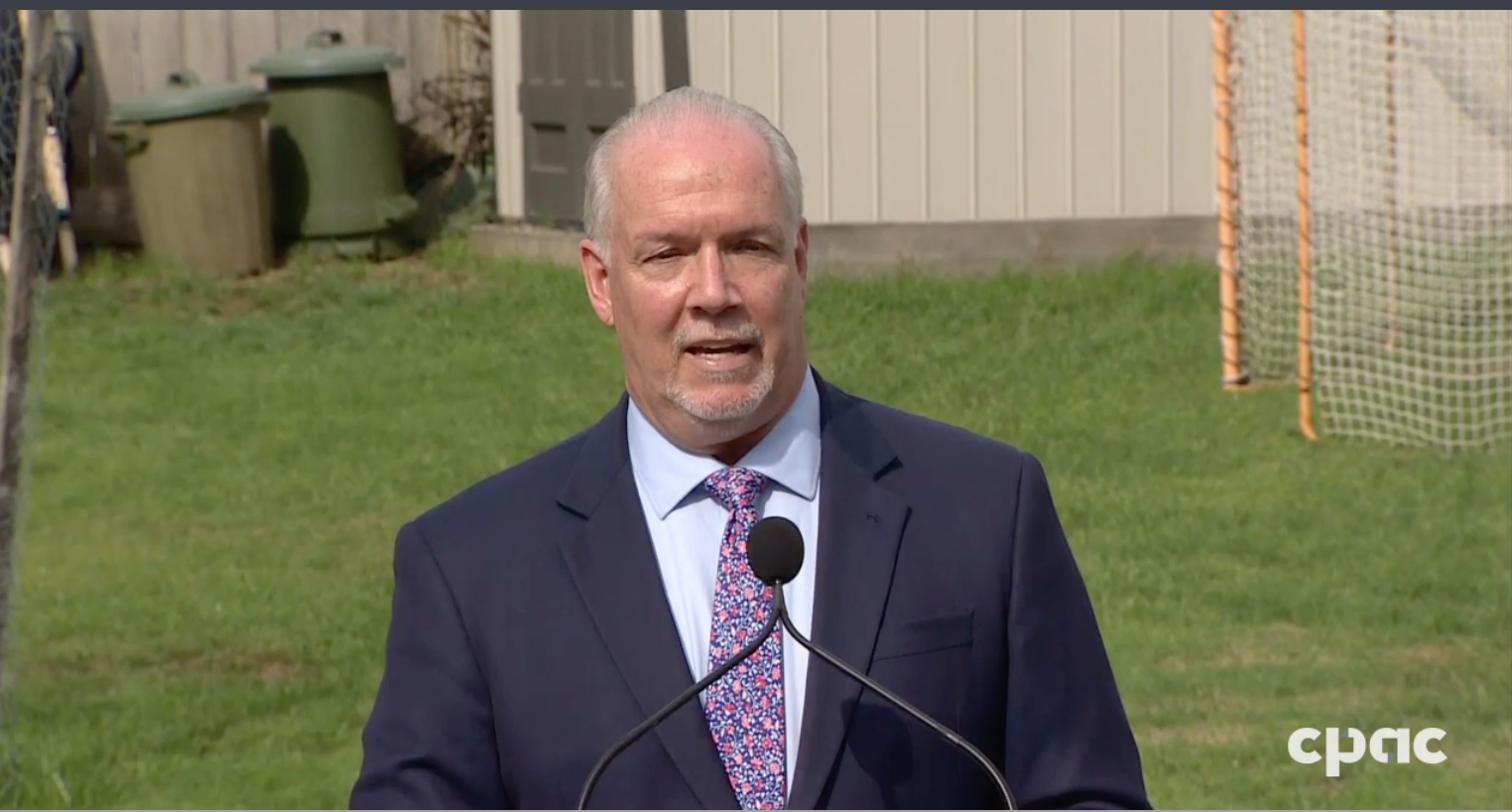

In the wake of the Ontario and Alberta scandals, Port Coquitlam’s Brad West Tweeted Jan. 2: “Not surprised at all by the # of politicians caught far from home. Elitism permeates the political class, they think they’re better, rules are for the people they ‘govern’. The examples of this are many, policy & otherwise, but this has hit public nerve. Don’t stop here.”

Port Coquitlam Mayor Brad West (Mackin)

Delta’s George Harvie told theBreaker.news: “I have not travelled. Cancelled my scheduled vacation in Maui. Did ask our City Manager the question, we do not know of any Delta elected officials or exec. staff that travelled out of the country since Nov. 7, 2020. Shame on those other elected officials who did.”

Abbotsford’s Henry Braun: “As far as I know, none of our senior staff or council members have travelled outside of B.C. since November 7, 2020. With respect to myself, I have not left B.C. since December of 2019. My wife and I were scheduled to go to Hawaii for 2 weeks in late March of 2020 but cancelled due to my concerns about COVID-19… I haven’t hugged my 90 year old mother since early March, although we visit often (outside and masked – she’s in a care home in Abbotsford).”

Lions Bay’s Ron McLaughlin: “It is unfortunate that you even have to ask this question. The disregard across the country for health orders by some puts us all at risk. Elected officials and senior staff should be held to the highest standard.”

Port Moody’s Rob Vagramov: “All in all, I think I’m up to six cancelled trips, including longstanding Hawaii plans with family for NYE. But I know it’s for the best. Counting down to 2021 with my spouse on our deck in quiet Port Moody beat any countdowns abroad, or parties I’ve been at, in the past.”

Mike Hurley (Burnaby), Mike Little (North Vancouver District), Linda Buchanan (North Vancouver City), Richard Stewart (Coquitlam), Jonathan Cote (New Westminster), and John McEwen (Anmore), responded directly to say they had not traveled. Ditto for representatives of Doug McCallum (Surrey) and Malcolm Brodie (Richmond).

A representatives of Metro Vancouver commissioner Jerry Dobrovolny said he has not traveled, nor has his executives. Chair Sav Dhaliwal said the same.

Also denying travel, school board chairs Carolyn Broady (West Vancouver), Carmen Cho (Vancouver), Jordan Watters (Greater Victoria) and George Tsiakos (North Vancouver).

Staff of B.C. Senators Yonah Martin, Larry Campbell and Bev Busson said they have not traveled. Sen. Mobina Jaffer said she has not traveled anywhere since Nov. 7. Sen. Yuen Pau Woo said he has been in Ottawa since August and has not traveled to B.C.

On the provincial scene, the NDP Government caucus said none of its MLAs holidayed outside B.C.

Deputy Solicitor General Mark Sieben went away three weeks and Deputy Health Minister Stephen Brown did not respond.

Don Zadravec (LinkedIn)

But Don Zadravec, the assistant deputy minister of Government Communications and Public Engagement, said by email: “On behalf of the Deputy Ministers’ Council, I can advise you that no Deputy Minister has travelled outside the country since November 7.”

He did not respond to a followup question about the whereabouts of Deputy Environment Minister Kevin Jardine, three-week absence auto-reply says he will be back Jan. 11.“I will not have Internet access during this time and am unable to answer your email until my return,” Jardine wrote.

BC Hydro CEO Chris O’Riley has not replied. Neither has the power utility’s media relations department.

Do you know of any politicians, senior bureaucrats, executives with public institutions, judges, CEOs or anyone else in power who vacationed in spite of public health orders? Contact theBreaker.news in confidence. CLICK HERE.

Support theBreaker.news for as low as $2 a month on Patreon. Find out how. Click here.

Bob Mackin (Updated Jan. 8)

Say it ain't