Bob Mackin

Hector Bremner, the Yes Vancouver party’s candidate for mayor on Oct. 20, is well-known for once being an aide to former Deputy Premier Rich Coleman. Background interviews with current and former BC Liberal insiders, and documents obtained by theBreaker, show that Bremner was a member of Christy Clark’s leadership campaign team in 2011.

Bremner, who ran the Touch Marketing consultancy at the time, was an organizer for Clark in Burnaby and New Westminster ridings. On the eve of the Feb. 26, 2011 party election to replace Premier Gordon Campbell, Bremner was one of three recipients of two email messages from Harry Bloy, the Burnaby-Lougheed MLA and Clark’s only supporter inside the BC Liberal caucus.

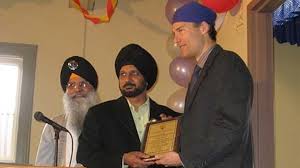

BC Liberal MLA Harry Bloy (left) and Hector Bremner at Bloy’s February 2011 fundraiser. (Flickr)

At 11:55 a.m. on Feb. 25, 2011, Bloy emailed Bremner at his Touch address, BC Liberal director of field operations Mark Robertson on his BC Liberal address and ex-Vancouver-Burrard MLA Lorne Mayencourt.

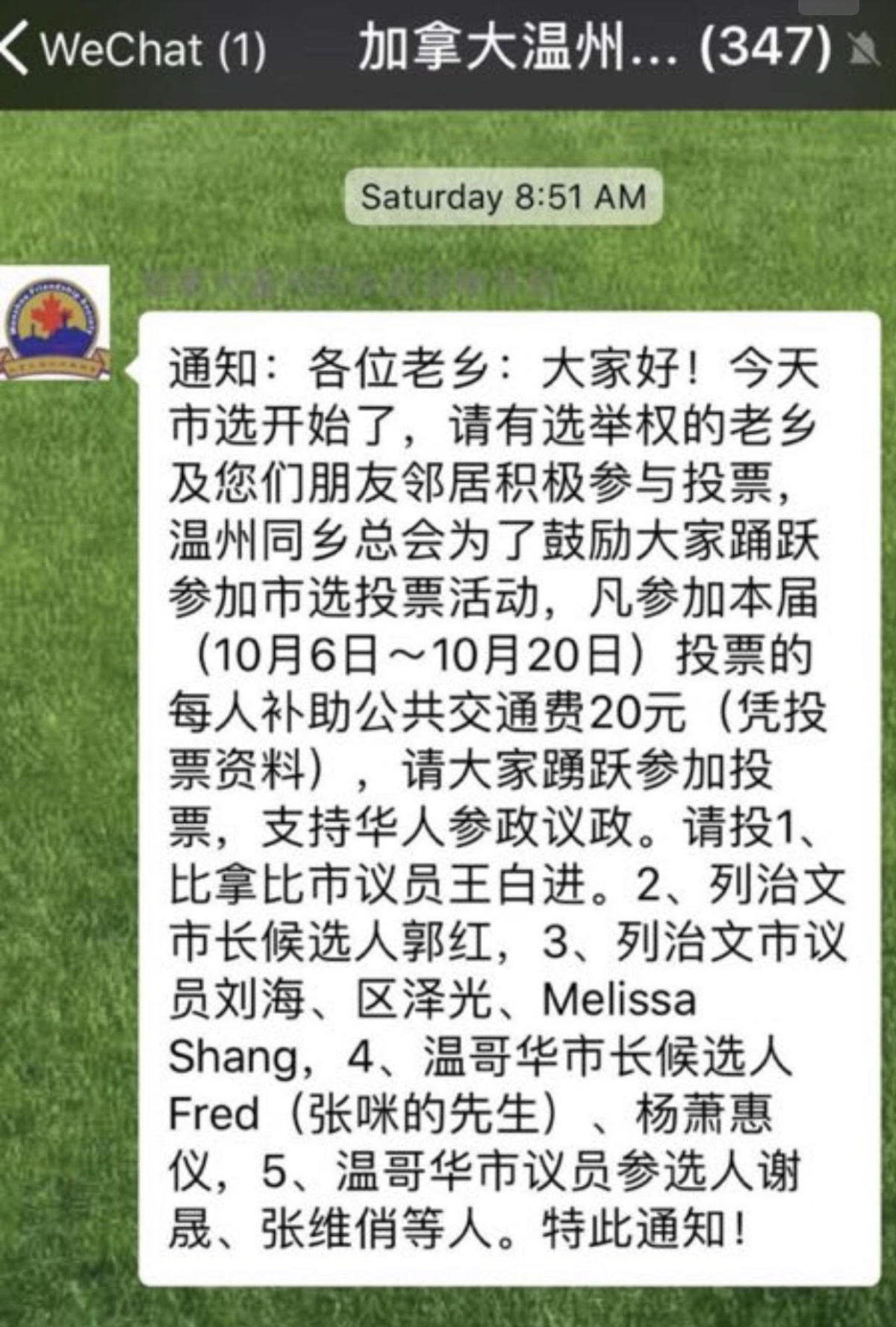

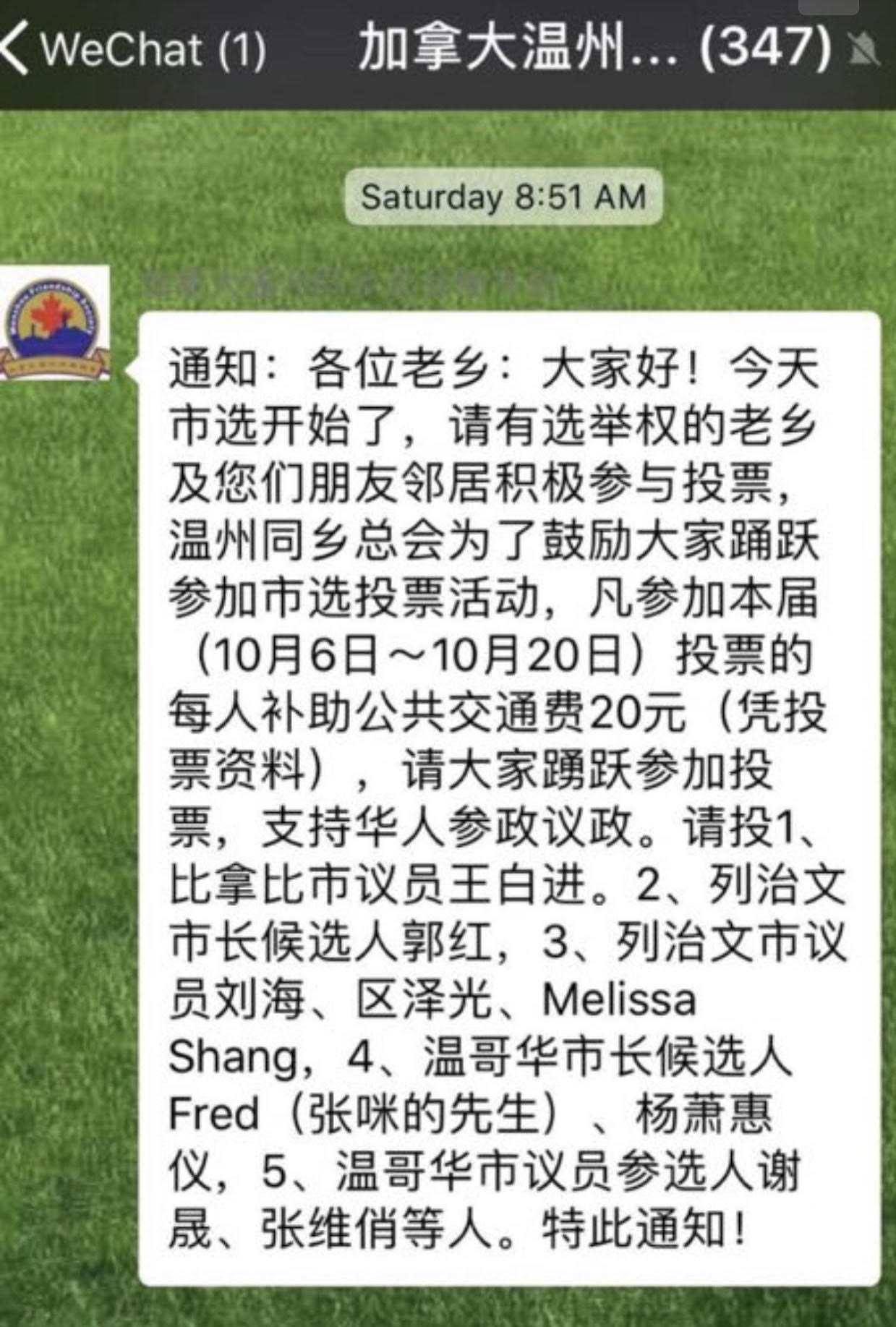

Bloy forwarded to Bremner, Mayencourt and Robertson what he had received 10 minutes earlier from one of his connections: a list of 77 personal identification numbers, with assurance that more were on the way.

Bloy’s email also included this short message: “Use different lines. Virginia, Filipino Community? Thanks, harry”.

Virginia was a reference to Bremner’s wife. As for the PIN numbers, the party sent the unique codes to every party member, so that they could cast a vote for a new party leader by phone or Internet.

At 5:50 p.m. on the same day, Bloy received a second batch of 22 PIN numbers, and forwarded them seven minutes later to Bremner, Mayencourt and Robertson. The subject line read “Fwd: pin # for CC E-Day.”

The two emails contained a total of 99 PIN numbers.

The messages do not indicate what Bremner, Mayencourt and Robertson did next.

The handling of PIN numbers for the 2011 leadership election was a surprise element of the investigation by Special Prosecutor David Butcher and the RCMP. Butcher was appointed in September 2013 after then-NDP leader Adrian Dix complained to authorities about possible violations of the Election Act.

During a hearing at Vancouver Provincial Court before Judge David St. Pierre in January of this year, Butcher confirmed that he found evidence of voting irregularities in the leadership contest that resulted in Clark’s victory over Kevin Falcon by a 340-point margin.

Clark’s third-ballot win was by a score of 4,420 to 4,080 points under the regionally-weighted, preferential ballot system.

Butcher told the court that the BC Liberal leadership election rules in 2011 did not prohibit proxy voting, so Bloy used his connections “and his connections’ connections,” Butcher said, to amass PIN numbers.

“Those connections gathered blocks of PINs which were supplied to Mr. Bloy, who provided them to other Clark supporters, who entered them online — block voting in a proxy process,” Butcher explained. “The Liberal Party has acknowledged difficulties with this process and it has adopted a different system [for the 2018 leadership election]… and, prudently, they sought advice from the RCMP about how to improve the integrity of the process.”

After becoming premier, Clark appointed Bloy as the Minister of Social Development in her first cabinet. Later in 2011, she transferred Bloy to Minister of State for Multiculturalism. Clark also named runner-up Falcon as deputy premier and finance minister. He eventually quit in summer 2012 to join Anthem Properties as a vice-president.

Falcon broke his silence after Butcher’s court revelation when he admitted to StarMetro reporter David Ball that he was not surprised.

“What you see here really speaks to a lack of transparency and integrity in the process that is highly problematic. The stakes were so high, and the premiership was in play,” Falcon said. “My team felt very upset as they were seeing irregularities, but there was no way I was going to make allegations to anyone without hard evidence. I’m not going to be a poor loser.”

Questions persist

The reason for Butcher’s appearance in court was the sentencing hearing for BC Liberal operative and ex-government communications director Brian Bonney. Bonney had pleaded guilty to breach of trust on Oct. 12, 2017, for his role in the ethnic vote-pandering scandal, also known as “Quick Wins.” St. Pierre sentenced Bonney to a nine-month conditional sentence, to be served at his home in Burnaby. A trial had been scheduled to run from Oct. 16, 2017 to Feb. 22, 2018. Butcher was planning to call dozens of witnesses from inside the BC Liberals.

In court, Butcher said that “the RCMP conducted a lengthy and challenging investigation into the case,” but most of the significant evidence came from email.

Clark (left) and Bremner, during the 2013 election campaign (Twitter)

“Most of the key witnesses from the Liberal party caucus and ministerial staff lawyered-up,” he said. “Two former cabinet ministers, Harry Bloy and John Yap, did not, under the advice of counsel, ever provide statements to the RCMP.”

A person familiar with the case told theBreaker that Bremner did not consent to an interview. Butcher did not return a phone call.

Bremner did not respond to multiple interview requests for this story. An email request to Bremner was also copied to Bremner’s lawyer, James Hatton, and campaign manager, Mark Marissen. Hatton was appointed in early 2013 to BC Hydro’s board by Clark, who is Marissen’s ex-wife.

theBreaker wanted to ask Bremner about his involvement with Clark’s campaign, whether he had any contact with Butcher or RCMP detectives, and whether he offered any assistance to their investigation.

Comment was also sought from Clark, Bloy, Mayencourt and Robertson. None responded.

After the leadership campaign, Bremner worked as a poll captain during Clark’s May 2011 Vancouver-Point Grey by-election win over the NDP’s David Eby.

Virginia Bremner became the receptionist at the Premier’s Vancouver Office in June 2011 and worked for Clark until July 2017, when the NDP formed government under Premier John Horgan.

Hector Bremner unsuccessfully ran for the BC Liberals in the New Westminster riding in 2013. He placed a distant second to Judy Darcy of the NDP. He was elected to Vancouver city council for the NPA in October 2017’s by-election, but the party board rejected his bid to become the mayoral nominee earlier this year. He started his own party, Yes Vancouver, for the Oct. 20 civic election. Bremner is awaiting the result of a conflict of interest investigation under city hall’s code of conduct.

His bio, on both the Yes Vancouver party website and the city council website, makes no mention of working on Clark’s political campaigns. It does say Bremner was appointed in 2013 to work in the international trade ministry (under Minister Teresa Wat) and that he later worked for the ministers of tourism and small business (Naomi Yamamoto) and natural gas development and housing (Coleman).

Bremner left the BC Liberal government at the end of January 2015 to join the Pace Group, the Vancouver public relations and government relations firm that, coincidentally, worked on Falcon’s 2011 leadership campaign.

When he joined Pace, Bremner registered to lobby the BC Liberal government for Steelhead LNG. His rival for the 2017 NPA by-election nomination, Coalition Vancouver city council candidate Glen Chernen, complained to the registrar of lobbyists. The $2,000 fine assessed to Bremner in February for not disclosing his former employment under Coleman was overturned on a technicality in August.

“As a father and a husband, Hector Bremner strives to lead by example and never shy away from doing what is right,” his bio states.

Support theBreaker.news for as low as $2 a month on Patreon. Find out how. Click here.

Bob Mackin

Hector Bremner, the Yes Vancouver party’s