Exclusive: John Furlong’s Olympic book in Chinese, but controversial content remains the same

Bob Mackin

The Olympic flag will pass to Beijing 2022 at Sunday’s PyeongChang 2018 closing ceremony, and the former CEO of Vancouver 2010 is already poised to capitalize on the return of the five-ring circus to China.

John Furlong’s 2011 memoir, Patriot Hearts: Inside the Olympics that Changed a Country, was published last summer in Chinese with the blessing of Xi Jinping’s government. theBreaker obtained a copy and translated several chapters of the book, which is known in China as The Sun Finally Shines.

Covers of Furlong’s 2011 book and the 2017 Chinese edition.

theBreaker compared the most-controversial sections of the English edition with the Chinese edition and found they are substantially the same, despite a high-profile international controversy that raged for more than three years.

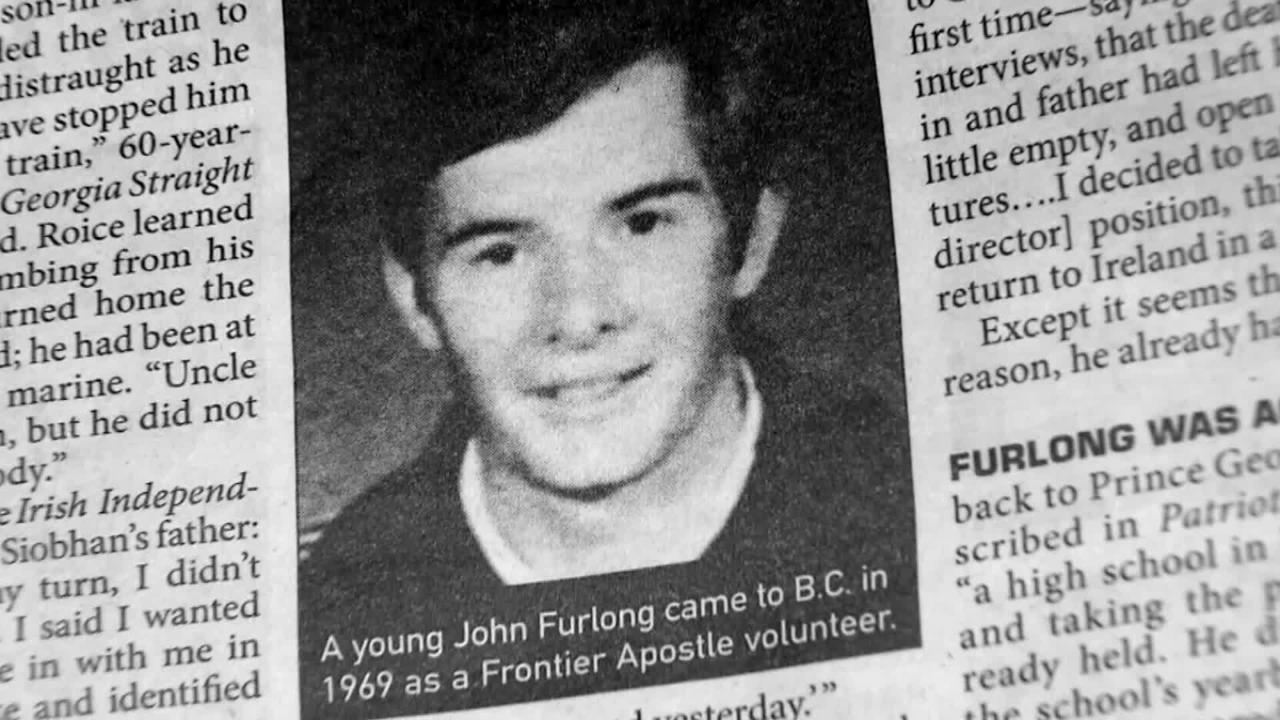

Errors and omissions in the original English publication inspired journalist Laura Robinson’s September 2012 exposé in the Georgia Straight newspaper, which was headlined John Furlong biography omits secret past in Burns Lake.

Just like the English edition, the translation of the Chinese edition includes Furlong’s anecdote about leaving his native Ireland and traveling to Canada on an autumn day in 1974, with his wife and their son and daughter, and meeting a customs officer in Edmonton who told him “Welcome to Canada, please make us better.”

Furlong wrote that he was on his way to a teaching job at a Catholic high school in Prince George, British Columbia. However, Robinson revealed that Furlong had already been in Canada. He originally came in 1969 as an 18-year-old to work as a gym teacher at the Immaculata Catholic elementary school for aboriginal children.

Forty-three years later, several students accused him of mental, physical and sexual abuse.

Furlong denied all the allegations and the RCMP did not recommend charges. None of the allegations has been tested in court. On the day that Robinson’s feature was published, Furlong’s co-author, Gary Mason, admitted that Furlong never told him about his time in Burns Lake. Furlong said that he didn’t include his time in Burns Lake in Patriot Hearts because it was “fairly brief and fairly uneventful.”

Furlong filed, but later withdrew, defamation lawsuits against Robinson and the Georgia Straight. Robinson countersued Furlong for defamation, but a judge ruled in September 2015 that Furlong had a right to defend his reputation.

Laura Robinson’s exposé in the Georgia Straight, Sept. 27, 2012.

Cathy Woodgate, one of the former students who alleged abuse, wrote an open letter to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in November 2015, asking for Trudeau to remove Furlong from chairing the federally funded, Canadian Olympic Committee affiliate, Own the Podium.

At its annual meeting in July 2016, the Assembly of First Nations resolved to ask the federal government for a “thorough and impartial investigation” into allegations that Furlong abused aboriginal students.

Furlong travelled to the PyeongChang Olympics in his capacity as chair of Own the Podium. He also leads a Canadian Olympic Committee group that is advising Calgary on a potential bid for the 2026 Winter Olympics.

Russian intrigue, Korean bribery

Just like the English edition, the translation of the Chinese edition mentions the death of his cousin, Siobhan Roice, after a terrorist car bomb exploded in Dublin in spring 1974. Furlong claimed that his father Jack was never the same after he identified Roice’s body at a makeshift morgue.

The English translation of the Chinese edition of Patriot Hearts reads:

However, everything changed after the afternoon of May 14 (sic), 1974. On this day, the life of our family has been completely changed…

The government urged people who lost their loved ones to go to a temporary mortuary in the city centre to claim their bodies. It was too unbearable for my aunt and uncle, and their home was 130 kilometres from the city centre. My father volunteered to take on this task. Later, he described the scene as a temporary morgue brutal beyond the imagination of people. Bombs exploded people into pieces, broken bodies were collected into bags, my father can only confirm the body of the ring by the fingers of Siobhan.

Robinson interviewed Roice’s brother Jim and quoted from a 2003 Irish newspaper interview with her father Ned, who said he found Siobhan’s body intact after the May 17, 1974 attack.

Robinson’s lawyer, Bryan Baynham, challenged Furlong’s chronology and credibility in B.C. Supreme Court on June 23, 2015. Evidence showed that Furlong had returned to Ireland in 1972 after he was the victim of an assault during a Prince George amateur soccer game that he refereed.

Furlong told the court that the date of his move to Canada was “frankly, irrelevant.”

“You didn’t arrive in Canada as a landed immigrant until 1975,” Baynham said.

“I’ll give you this,” Furlong replied. “I won’t say it was 1974.”

From the 2017 Chinese edition of John Furlong’s 2011 memoir.

As for his late cousin, Furlong maintained in court that Siobhan was “blown apart” and that “my version of the facts is true.” He told the court that Siobhan’s true condition was withheld from her mother for fear of adding to her grief. But he could not recall the last time he had spoken with the Roices.

The head of Justice for the Forgotten, an Irish organization that represents victims of the 1974 terrorist attack, told this reporter in 2015 that she knew the Roices and confirmed that Siobhan’s father had travelled to Dublin to identify his daughter. “She was killed, almost certainly instantly, but was not ‘blown apart’,” said Margaret Urwin.

Like the English edition, the Chinese edition also contains sections that raised the eyebrows of the International Olympic Committee in 2011. Furlong had written about a non-monetary deal with the Mayor of Moscow, Yuri Luzhkov, to gain Russia’s votes in the host city election. He also alleged he saw members of South Korea’s bid team distribute watches and CD players during a meeting in Buenos Aires. The IOC had strict rules banning gifts after the Salt Lake 2002 bidding scandal.

Furlong wrote that he travelled to Moscow with international bobsled executive Bob Storey to give Luzhkov advice on bidding for the 2012 Summer Games (which eventually went to London) in exchange for Russia’s six or seven votes.

Vancouver edged PyeongChang’s 2010 bid by just three votes in the second ballot victory at Prague in July 2003. PyeongChang lost again in 2007 to Sochi, Russia for the 2014 Winter Games, but finally won the 2018 hosting rights in 2011.

The IOC, in May 2011, opted against disciplining Furlong. ”There is no evidence of wrongdoing and this is supported by John Furlong’s confirmation that no IOC members were involved in either case,” the IOC said at the time.

The Chinese edition was published in mid-2017 by China Pictorial Publishing House with support of the Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries and China Friendship Foundation for Peace and Development.

All are arms of the Communist Party government.

The English title, lifted from O Canada, was changed for the Chinese market to The Sun Finally Shines.

“The original title ‘Patriot Hearts‘ was about Canadian people’s patriotism, which created some distance for Chinese readers,” publisher Yu Jiutao told China.org.cn. ‘The Sun Finally Shines is actually the title of one of its chapters. We wanted it to sound inspiring to Chinese readers, as it is.”

Bob Mackin The Olympic flag will pass to