First to report: B.C. Place name for sale… again

Bob Mackin

theBreaker.news was first to report on Feb. 4 that the NDP government is putting B.C. Place Stadium’s naming rights on sale, seven years after then-premier Christy Clark scrapped a lucrative deal with Telus and ignited a firestorm of controversy.

When it published a new request for proposals on the BC Bid procurement portal, PavCo set a May 15 deadline for bids, pledged a shortlist by June 7 and notification of bidders by July 24. The schedule for renaming the stadium is to be announced. PavCo wants to sign a 20-year contract with a sponsor that has “the financial capacity to treat this as a cornerstone of their sponsorship and marketing strategy in Canada,” the tendering document stated.

PavCo said it will evaluate bids based on a five-point checklist that includes: the sponsor’s brand strength, resources and suitability; brand activation strategy and budget; community engagement concepts; sponsorship fees and term; and PavCo’s confidence in the proponent. PavCo enlisted the expertise of sports marketing and branding expert Yoeri Geerits of Calgary-based threesixtythree inc. Geerits is a former senior vice-president of Nielsen Sports Canada.

Whitecaps’ captain Jay DeMerit (left) and Premier Christy Clark at the Sept. 30, 2011 reopening of B.C. Place Stadium (Whitecaps)

“We’re going to be excited to see who puts their name forward,” Tourism and Culture Minister Lisa Beare said in an interview with theBreaker.news. “At the end of the day we’re going to be looking for the best fit and for the best value for British Columbians.”

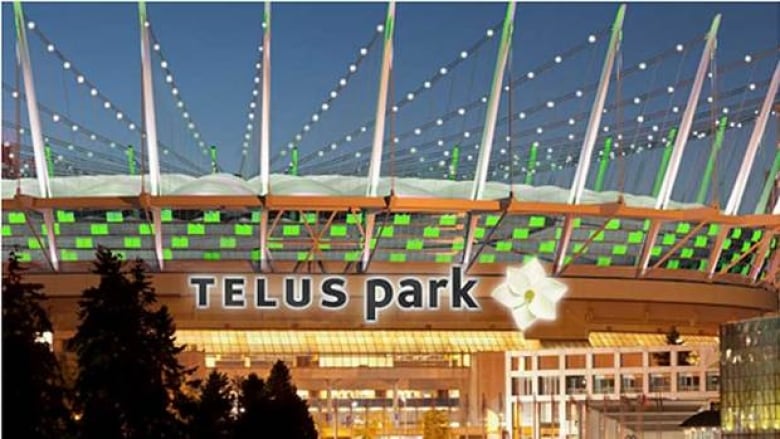

Telus had a 20-year contract worth $40 million to change the 1983-opened venue’s name to Telus Park. Pat Bell, the BC Liberal minister responsible for PavCo in 2012, was heavily criticized for claiming B.C. Place was an “iconic” name and that Telus “did not provide the best value for taxpayers.”

Asked whether Telus would be receive any special consideration, Beare said: “It’s going to be a fully open and transparent process to ensure the best possible outcome, so any company that is interested will be encouraged to apply.“

When the BC Liberal government cancelled the Telus deal, taxpayers were stuck with a $15.2 million bill to buy Telus-installed equipment, including video screens, software and wifi.

Longtime BC Liberal bagman Peter Brown quit the PavCo board in disgust. The B.C. Place naming rights controversy was cited by John van Dongen when he quit the BC Liberal caucus in late March 2012. “When more and more decisions are being made for the wrong reasons, then you have an organization that is heading for failure,” van Dongen said in the Legislature.

Lisa Beare, NDP minister responsible for PavCo (BC Gov)

A “telecom war” broke out in June 2011 when the Clark cabinet gave Telus a 10-year, government-wide telecommunications supply contract worth $1 billion after abruptly ending a two-year bidding process on nine separate contracts. Bell, Rogers and Shaw threatened legal action.

Bell was already the top sponsor of the Vancouver Whitecaps, majority owned by Clark friend Greg Kerfoot. The Whitecaps referred to the playing surface at Empire Field and then B.C. Place as “Bell Pitch.” Neither the Whitecaps nor the B.C. Lions contributed to the $514 million, taxpayer-funded renovation and installation of a German-engineered retractable roof that was leak-prone for more than two years.

“We were only just made aware that this announcement was taking place,” Tom Plasteras, the Whitecaps’ director of broadcast and communications, said Feb. 4. “We are not in a position to comment at this time except to say that as a primary tenant we anticipate being an integral part of this naming rights process.”

While in opposition, the NDP slammed the BC Liberals for fast-tracking B.C. Place rejuvenation, because the renovation or replacement of the decaying St. Paul’s Hospital and seismic reinforcement of public schools were bigger priorities for British Columbians.

In 2013, then-PavCo critic Spencer Chandra Herbert complained to Auditor General John Doyle, seeking a value for money audit because the B.C. Place project was originally estimated at $100 million after the roof ripped and collapsed in 2007 under snow and sleet. Russ Jones replaced Doyle as Auditor General before the BC Liberals won the 2013 provincial election and the B.C. Place audit never proceeded. During that campaign, NDP leader Adrian Dix promised to explore privatization of the stadium.

The renovation, which began before the 2010 Winter Olympics, was supposed to be financed by the sale of naming rights and lease revenue from a casino next door. Parq Vancouver finally opened in fall 2017. An amount equal to the first three years of lease revenue was paid last year to the Musqueam Indian Band, under an $8.5 million land claims compensation pact negotiated by the previous BC Liberal government. Last week, Ottawa-based PBC Group announced the buy-out of Las Vegas-based Paragon Gaming’s stake in the money-losing casino for an undisclosed sum.

BC Place Stadium was supposed to become Telus Park, but the BC Liberal government cancelled a $40 million agreement. (Telus)

For the year-ended March 31, 2018, B.C. Place ran a $12.12 million deficit, more than $5 million worse than the previous year. According to official 2018 attendance figures released by PavCo to theBreaker.news under the freedom of information law, the Vancouver Whitecaps averaged 18,211 per game, while the B.C. Lions drew an average 14,769. Beare said she did not consider soft attendance for the stadium’s two anchor tenants to be a challenge for the sale of naming rights in 2019.

After the NDP came to power in 2017, it installed lawyer Ian Aikenhead as the chair of the PavCo board, with orders to improve the balance sheet. Aikenhead was president from 1992 to 2001 of the Pacific National Exhibition when it was a B.C. Crown corporation.

Meanwhile, on Jan. 25, an Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner adjudicator ruled in favour of theBreaker.news, which sought the uncensored, 27-page sponsorship addendum agreement with the Whitecaps.

“The agreement sets out the locations within B.C. Place that the Whitecaps can use for sponsorship activities and how the Whitecaps can use them,” wrote adjudicator Erika Syrotuck. “The agreement also addresses how the potential future sale of naming rights to B.C. Place Stadium would affect the Whitecaps.”

The adjudicator rejected claims that release of the contract would harm PavCo finances and reveal Whitecaps’ trade secrets.

“Finally, I do not agree with the Whitecaps’ assertion that a purpose of [the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act] is to protect the interests of private organizations. The purposes of FIPPA are set out in section 2 and include giving the public a right of access to records and specifying limited exceptions to the rights of access. Private organizations that contract with public bodies do so with the knowledge that public bodies are subject to FIPPA.”

Syrotuck ordered PavCo to disclose the contract by March 11.

Support theBreaker.news for as low as $2 a month on Patreon. Find out how. Click here.

Bob Mackin theBreaker.news was first to report on